Countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and South-Eastern Europe (SEE) probably understand better than most the impact of the war in Ukraine. Many have close relationships with the government in Kiev, while Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Moldova and Romania all share borders with the country, so are acutely aware of the scale and impact of the war. The need to strengthen energy security and become less dependent on Russian fossil fuel supplies is therefore uppermost in the minds of politicians and businesses in the region.

The focus on energy security which the war has caused has also given added impetus to the European Union’s Green Deal agenda, as well as the broader European energy transition. The EU Commission’s ‘Fit for 55’ legal package, unveiled in July last year, sets itself a binding target of reaching climate neutrality by 2050. As a first step, and to emphasize the importance of picking up the pace of cutting greenhouse gases, it has committed to cutting emissions by at least 55% by 2030 and increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix to 40% by the same year. The package also introduces the revision of the EU’s emissions trading scheme and its carbon border tax mechanism, promoting energy savings and other measures.

For the CEE and SEE EU member states, these targets are ambitious, especially when in some countries – such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia or Bulgaria – there is still a large dependency on fossil fuels for energy generation, district heating and transport. The regions are still dealing with the legacy of energy intensive industries, often obsolete energy assets and underinvested energy grids, which are unable to accommodate digital and smart energy distribution.

Meanwhile countries in the western Balkans – where fossil fuel dependency is even greater and the share of renewable energy only half that in the CEE and SEE regions – are determined to join the European decarbonisation agenda by introducing their own renewable energy targets, promising to phase out coal usage and introduce internal energy trading mechanisms. In that context, it is critical that the energy integration, both inside the CEE and SEE regions and with the rest of Europe, is strengthened, particularly when it comes to grid connectivity, with the transmission infrastructure reflecting both the geopolitical environment and technological changes.

The escalation of the war in Ukraine, followed by the cutting of gas supplies from Russia to Europe and the subsequent soaring of electricity and gas prices which are causing a cost of living crisis, has brought a further acceleration of the European decarbonisation agenda. The European Commission announced the new REPowerEU plan in May this year, while two months later member states took a joint decision to reduce the use of gas by 15% during the winter. The REPowerEU agenda not only elevates the targets for European renewable energy generation capacities (to 45% by 2030), it also pushes for stronger energy savings, greater transport electrification, more solar energy in buildings, renewables-based district heating, clean industries and green hydrogen. Planned carbon pricing reforms and the Carbon Adjustment Border Mechanism (which puts a carbon price on imports of certain goods from outside the EU) will only strengthen the competitiveness of the bloc’s renewable energy and decarbonisation sector.

For countries in the CEE and SEE regions, the war is creating huge challenges. Being heavily dependent on fossil fuels from Russia (by up to 100% in some cases), the war risks making the ability to meet the EU’s goals without causing damage to the regions’ businesses and consumers a painful experience. In addition, affordability is becoming a pressing issue: not only are gas prices soaring, putting pressure on businesses and households, but countries in this part of Europe also have some of the lowest incomes of any on the continent. A need for a transition support towards these ambitious goals is therefore important.

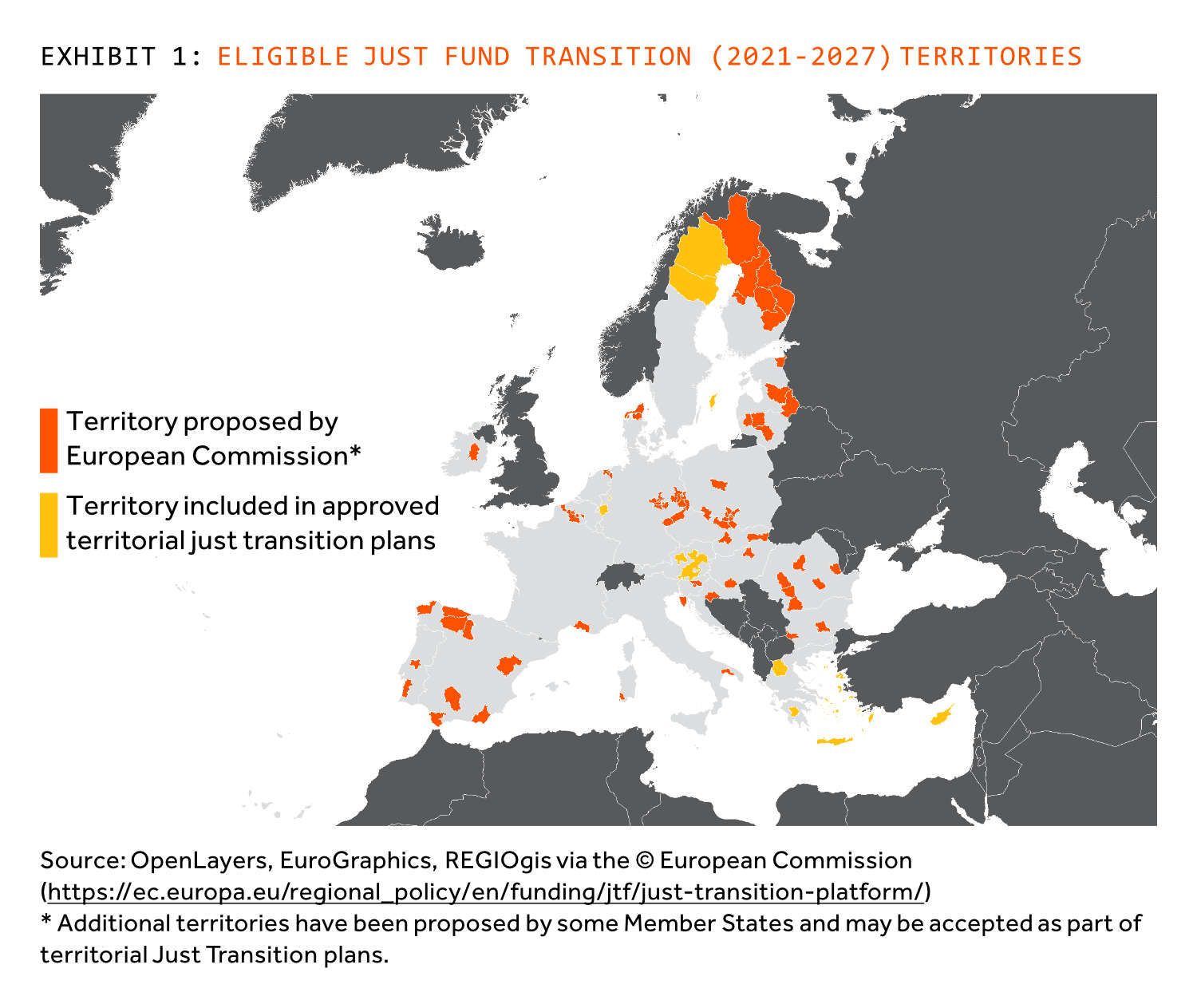

For investors, the situation is made complicated by the different financial landscape, as well as regulatory models, faced by countries that are in the EU, and those that are outside. EU countries – and in particular Central and Eastern Europe member states – will have access to funds through loans and grants from NextGenerationEU, the €800bn temporary recovery package to help repair the economic and social damage caused by Covid-19, as well as from the EU Modernisation Fund, which is dedicated to supporting 10 lower-income member states. Then there is the €17.5bn Just Transition Fund to address the social and economic impact of the transition to climate neutrality. The Just Transition fund will prove hugely beneficial to countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania and Greece, which are suffering from the social costs of the energy transition. Meanwhile the investment environment is also becoming very encouraging. CEE and SEE countries are reforming their support models, REPowerEU works on improved permitting for renewable energy installations, while the EU taxonomy adds tighter requirements on financial institutions and large corporates to look for renewable energy sources, push for energy savings, and disclose relevant policies (Exhibit 1).

The success of the energy transition in Europe will only be possible when private funds support the available EU money. Financial institutions in Europe have made a fundamental shift towards decarbonisation over the last few years. The majority of European banks and institutional investors developed their own net zero commitments, undertook to grow their green asset ratios, and focus on green financing. The assessment of risks associated with the environment and climate change is better understood, through the stress testing performed by the European Central Bank (ECB) and other European regulations. To comply with the EU taxonomy and climate-related disclosure requirements (under Europe’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and its Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)) banks are increasing their focus on green investments and financing, with a growing variety of instruments including green mortgages, green savings loans, as well as green and sustainability linked bonds, all of which serve to improve their green assets ratios and better meet the EU Capital Requirements Directive’s Pillar 3 obligations. European banks are also strongly represented in the western Balkans and Eastern Europe, so the best standards should spill over beyond the EU’s borders.

Taken together, providing more renewable energy across both the CEE and SEE regions represents a huge investment opportunity for the private sector. To meet the expected targets, the region should double its renewable energy sources. However in some of the SEE countries, the challenge will be greater. Many countries are starting from a low base when it comes to renewable energy capacity. There will therefore be a significant need to invest not just in renewable power, but in energy storage, smart grids, digitalisation, green hydrogen and other technologies. Governments will need to build infrastructure that is suitable for renewables transmission. Many lack the capital and the experience to make the changes themselves.

While the availability of EU funding and grants is a key component, there is a growing demand for commercial leverage and capital in the CEE and SEE regions. The area is less developed in dealing with other market instruments. Contracts For Differences (CFDs) exist in only a few countries in the regions and are in their infancy (notably in places including Romania and Serbia). There is also little experience with commercial PPAs in comparison to some Western European countries, while there is a growing complexity in energy management thanks to the increasing role of energy storage, grid integration, future CO2 storage and management, selection of the right technology mix and digital services.

All of this requires strong experience and skills when managing renewable portfolios, with the need also to be aware of the social aspects, affordability and the wellbeing of local communities. Smart money and experienced investors with significant operational skill such as Actis – which has the sector experience and knowhow in structuring deals, energy management and technology – can play a significant role in helping the region overcome its challenges. Indeed, harnessing private capital will be vital, since the scale of the challenge across the continent can appear daunting.

More private capital will therefore be key to the regions’ futures. Harnessing the sector’s funds and expertise will be critical if Europe is to meet its clean power and energy security needs. The requirement for more renewable power throughout the CEE and SEE regions was evident even before the war began. The crisis has therefore only added a growing urgency to the need for a speedier energy transition.

Lucyna Stanczak-Wuczynska is Chair of BNP Paribas Bank in Poland and a member of the Supervisory Board of Erste Bank in Hungary. She is a Senior Adviser to Actis.