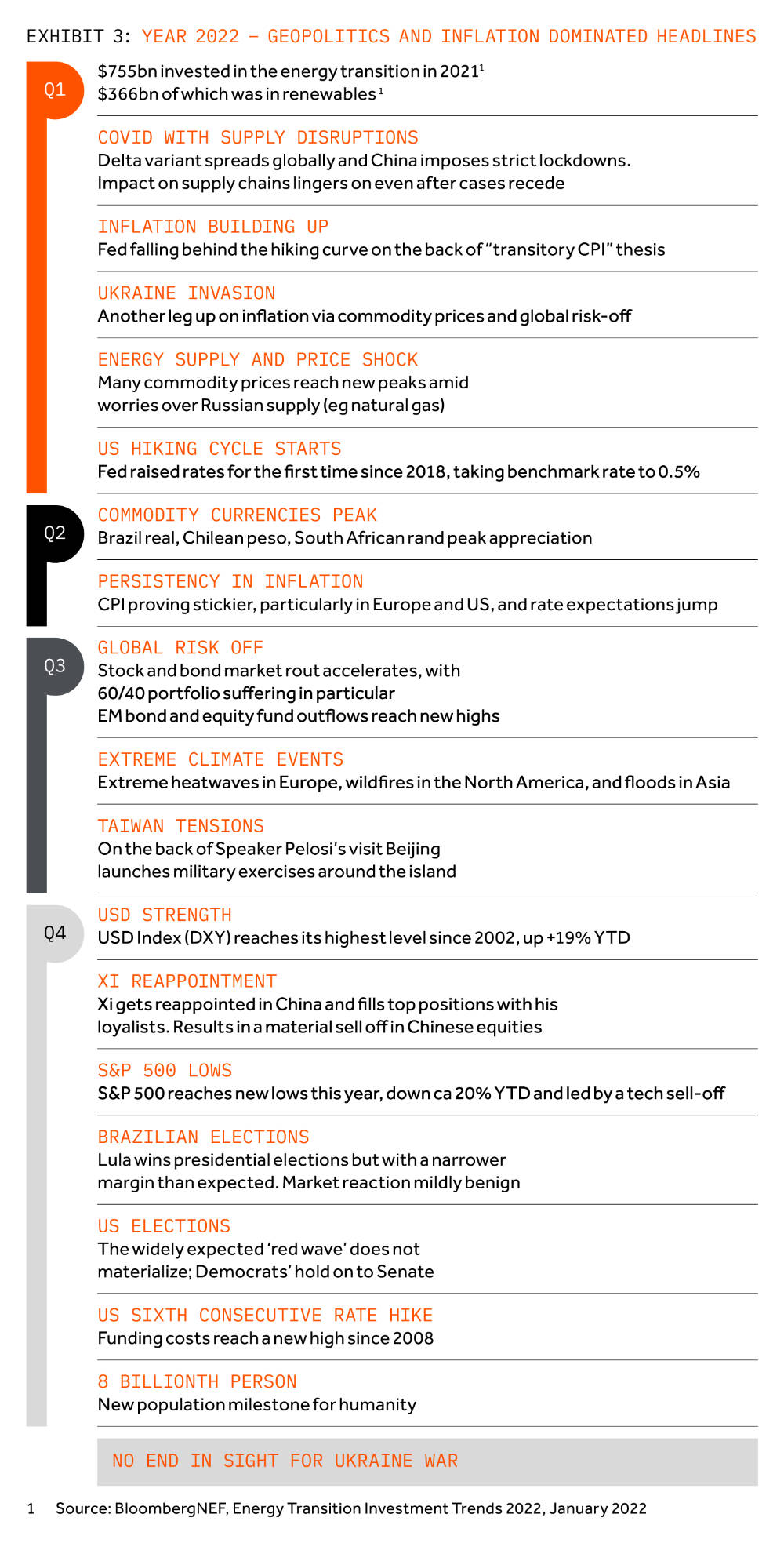

2022 has proved to be a trying year for portfolio investors. Falling stock and bond markets, rising inflation and interest rates and a deteriorating global economic outlook have proven to be gale force headwinds. In US fixed income, we have seen the worst year since 1788, the worst drawdown in real terms since 1931 for a 60-40 US dollar bond equity portfolio, and near $30 trillion of wealth destruction overall. No wonder pessimism and uncertainty abound. And that’s before you get to geopolitics.

Inflation and growth prospects and associated policy decisions will dominate the outlook again into 2023.

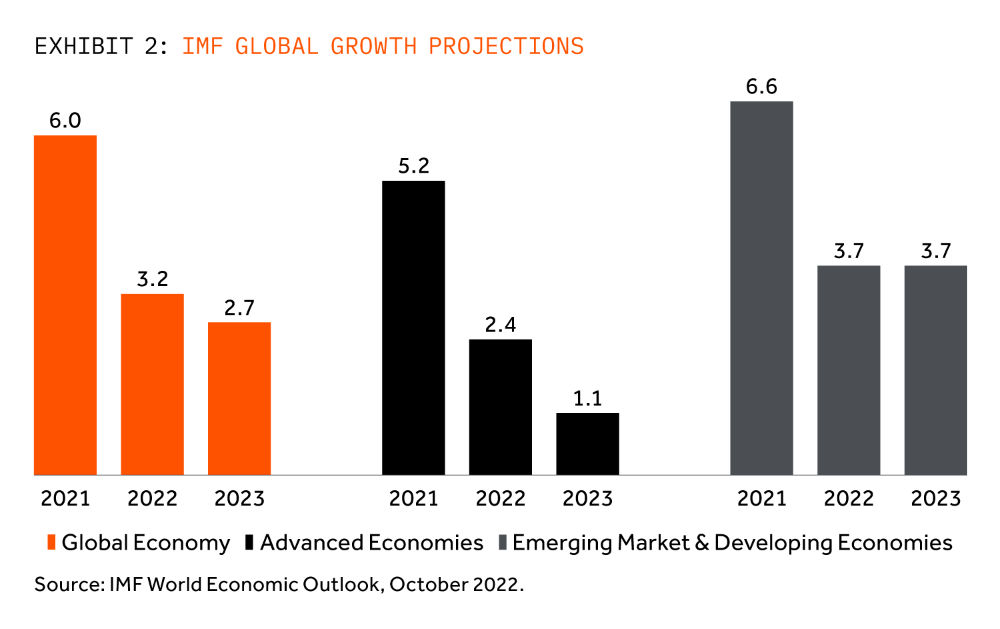

World growth forecasts continue to fall. The October IMF World Economic Outlook saw 2023 growth reduced to 2.7% from 2.9%. As ever the decimal points don’t matter, rather it is the direction of travel. High frequency indicators such as shipping rates, business confidence surveys and commodity prices all point in the same negative direction. Inflation has been particularly stubborn in 2022, necessitating and advancing a tighter policy mix from Central Banks which, in turn, has impacted economic growth and financial market returns.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine was the proximate event that let the inflation genie out of the bag. The supply side shock for energy and commodity markets magnified price pressures that were already running high even before the invasion. Given that energy and food are non-discretionary expenditure items, the impact on Europe has been profound. Even more worryingly the pressure on poorer nations in Africa, South Asia and Latin America has sown the seeds of humanitarian as well as economic tragedy.

These issues have been magnified by the strong US dollar. The US dollar index (DXY) rose by more than 13% through October 2022 year to date hovering around levels last seen in 2002.

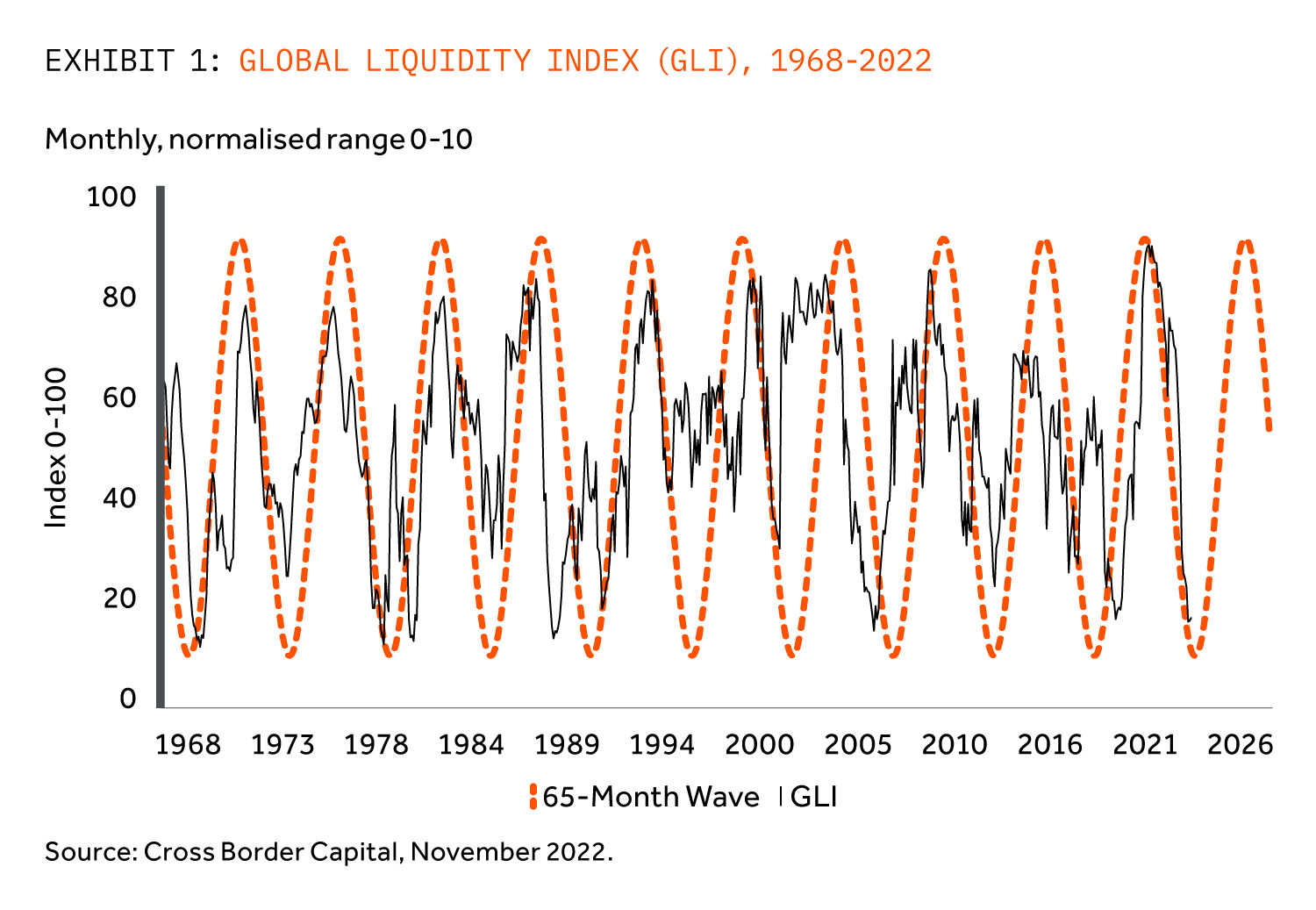

Financial policies to curb inflation added to the woes. Cross Border Capital, a London research boutique with whom we partner for FX advice, estimates that as of November 2022, there was no Central Bank easing policy – anywhere. This is unprecedented in this millennium. Cross Border’s widely followed Global Liquidity Index hovers around levels only seen half a dozen times in the last 50 years (Exhibit 1). And liquidity matters to markets – a fact that the heavy declines on Wall Street confirm.

It is not all doom-&-gloom though

There is some better news as we turn the page on the calendar and enter 2023. Energy and food prices have come down materially from peaks of June. Slowing growth has brought the oil price back to pre-invasion levels. The World Bank calculates that the same is true for food prices. The Bloomberg Commodity Index -tracking 23 energy, metal and crop future contracts -has declined by 20% from June peaks, albeit it is still up 15% for the year. US monetary growth – running at 25% a year ago – is now around zero. One widely-held expectation looking into 2023, is that inflation may be close to peaking. The dollar- crudely the global price of liquidity given its dominance as the reserve currency – seems to be losing steam as well. Recessions tend to reduce cross border flows into dollars, and Cross Border’s projected 20% decline in 2023 US corporate earnings would seem to support the likelihood of lower portfolio flows. Easing prices for commodities and dollar denominated services such as shipping, ease the pressure on non-dollar countries and agents to purchase the greenback for transactional purposes.

Larger Emerging Markets have weathered the 2022 storm rather better than in the past. We are seeing projections of higher 2023 EM growth rates in contrast to Advanced economies, led in part by some post Covid recovery in China. The IMF October forecast for this group has risen to 3.7%, more than two points higher than for Advanced Economies (Exhibit 2). If achieved, the Emerging Markets group would experience its highest growth advantage over advanced economies since 2016. The residual impact of rising oil prices has also helped oil producers in the Gulf. Inflation too appears to be more benign for large Emerging Markets than Advanced Economies, the first time we have seen this phenomenon since 2008. And amidst the carnage for the Euro and Yen precipitated by a strong dollar, the Brazilian real and Mexican peso have strengthened this year as policy makers early moves got ahead of the curve, in stark contrast to Advanced Economies central banks.

China is worth some focus as we head into 2023

Zero Covid and the real estate crisis have together combined to limit growth this year. Of late, the Chinese authorities have begun to respond on a more co-ordinated and determined basis. The PBOC liquidity injections have effectively eased monetary policy. The property crisis is now being addressed by Central Government rather than cash strapped local authorities, whose revenues depend on land sales. And tellingly, the offshore RMB has drifted down, below policy levels observed consistently since 2015. Whilst we continue to think that Covid restrictions will remain in place until the end of the winter, there seem to be tentative moves to ease policy planned for the next few months. A weaker RMB is mildly deflationary for the world economy adding to the drift down of inflation concerns.

Next year remains extremely challenging on many fronts but we remain confident that long term inflation protected cash flows, energy transition and energy security and infrastructure contracted on a widely diversified global base remain attractive.

2023 may bring with it some likely and some more unlikely outcomes. Driven by slowing economies and peaking inflation momentum, looser policy – or more correctly less tight policy- is central to investor outcomes. It is clear in the Developed Markets world that tolerance for unfunded fiscal expansion is waning. Equally it is clear that absent further Quantitative Tightening, ongoing deficits will continue to see supply of long duration government bonds rise. But if the peak in inflation is already factored into the positive 2022 bond-equity correlation, this has the potential to reverse in 2023. Lower geopolitical tensions could help battered investment sentiment. A global recession means that stable cash flows such as those generated by infrastructure investment will remain in demand – this is foreshadowed by the relative outperformance in liquid markets of defensive stocks with low cash flow volatility relative to cyclicals. The Ukraine War means that energy transition and energy security will remain front of mind and funding (a feature we see in our discussions with banks over funding). This is a real development – the IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook report from October highlights that targeted renewables adoption, on aggregate, has accelerated because of Ukraine war. And the relative stability of large Emerging Market countries is also attracting attention.

No one will be unhappy to turn their backs on 2022 – a year dominated by headlines on geopolitics and inflation (Exhibit 3). Next year remains extremely challenging on many fronts but we remain confident that long term inflation protected cash flows, energy transition and energy security and infrastructure contracted on a widely diversified global base remain attractive.