If a week is a long time in politics-ask Theresa May- a year can seem like a long time in investment markets. This has certainly been true as for growth (or emerging) markets in 2018. A year ago sentiment was riding buoyant with a seemingly unstoppable rush to force as much exotica into portfolios.

Today everything has changed. EM bonds and currencies have fallen in value, crisis has engulfed Turkey and Argentina and extreme stress has been felt in South Africa, India and Indonesia among others. What has changed to send sentiment through 180 degrees? And will current fears deepen?

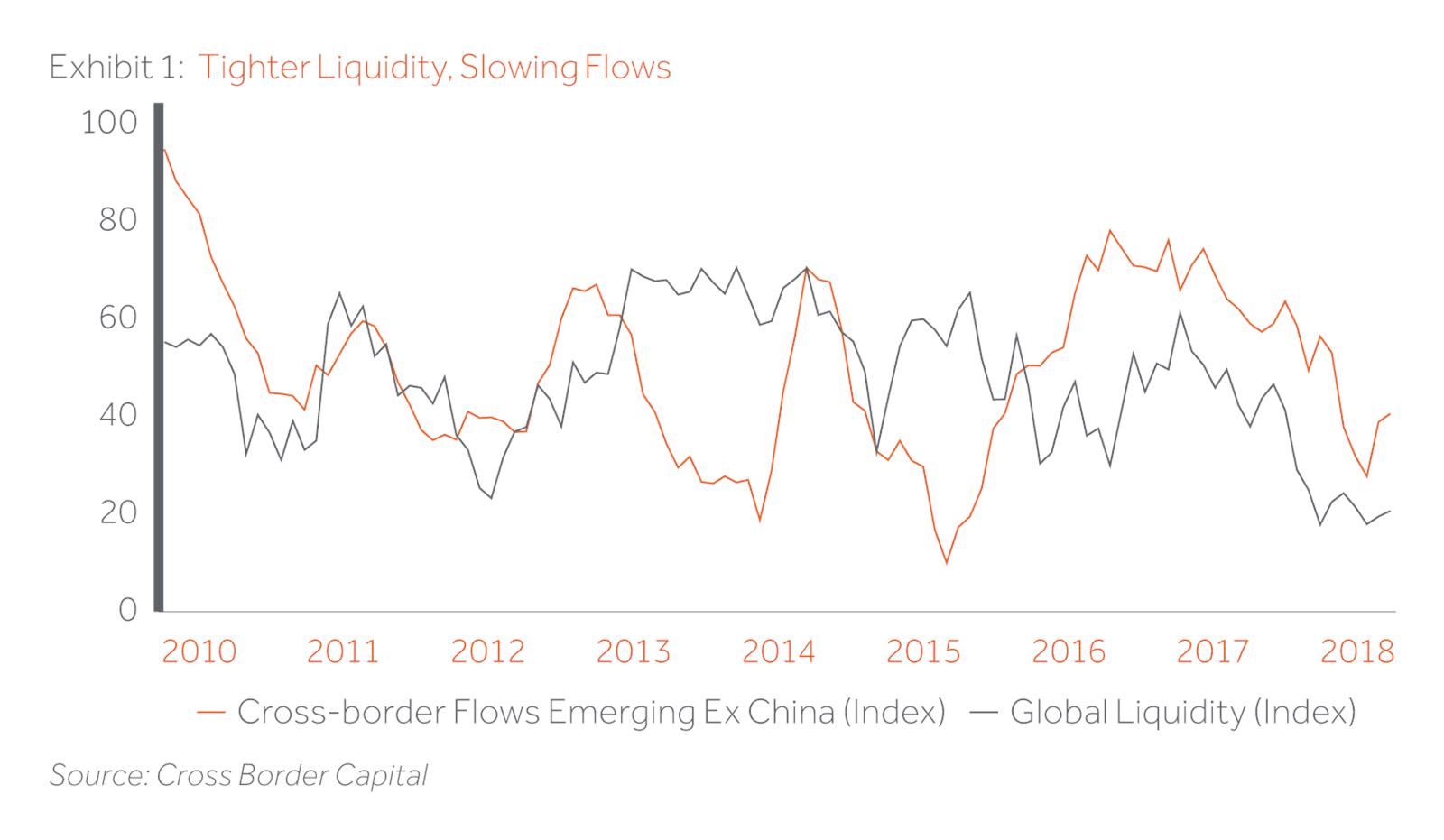

Firstly, the dollar strengthened as US rates rose. This has proved a ghastly cocktail for EM risk in the past and was so again in 2018. In parallel global central banks in total sharply decelerated their balance sheet growth. Cross Border Capital, a leading researcher on global liquidity conditions reckons that global and EM liquidity are now close to crisis levels. Their measure also includes the impact of private sector liquidity which has drained in recent times as activity and demand for funds accelerated. Given that portfolio flows have risen in importance relative to less volatile foreign direct investment the pass through to EM financial assets of ‘risk off’ is greater than ever.

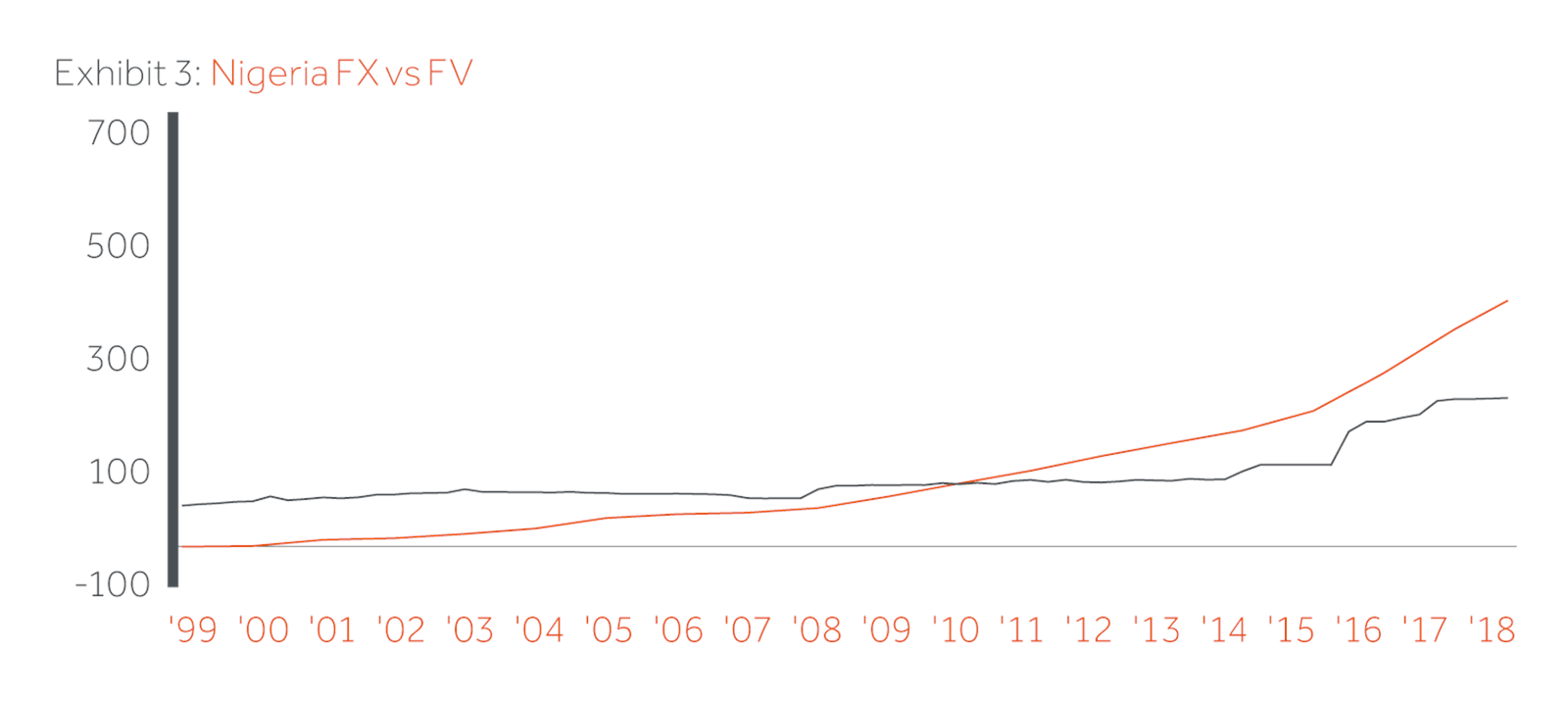

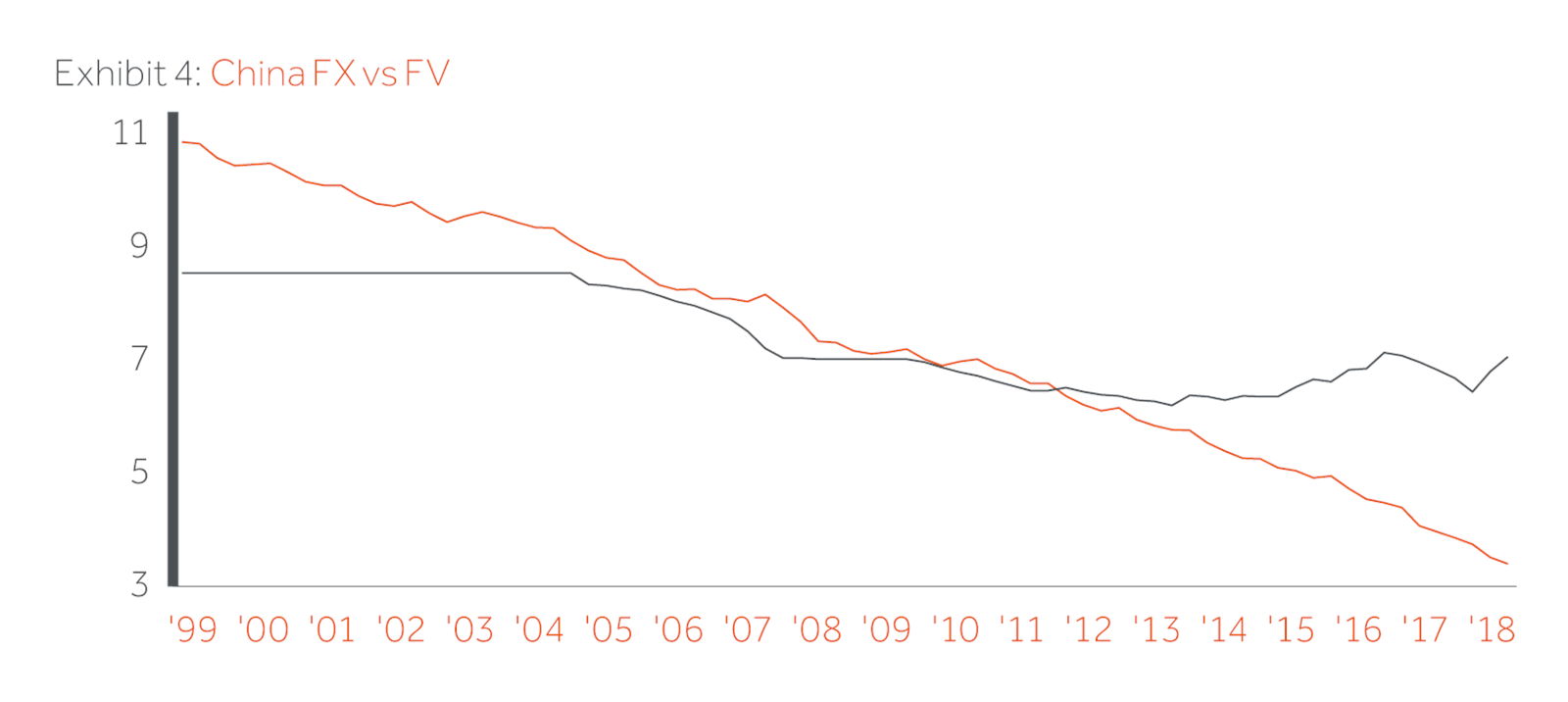

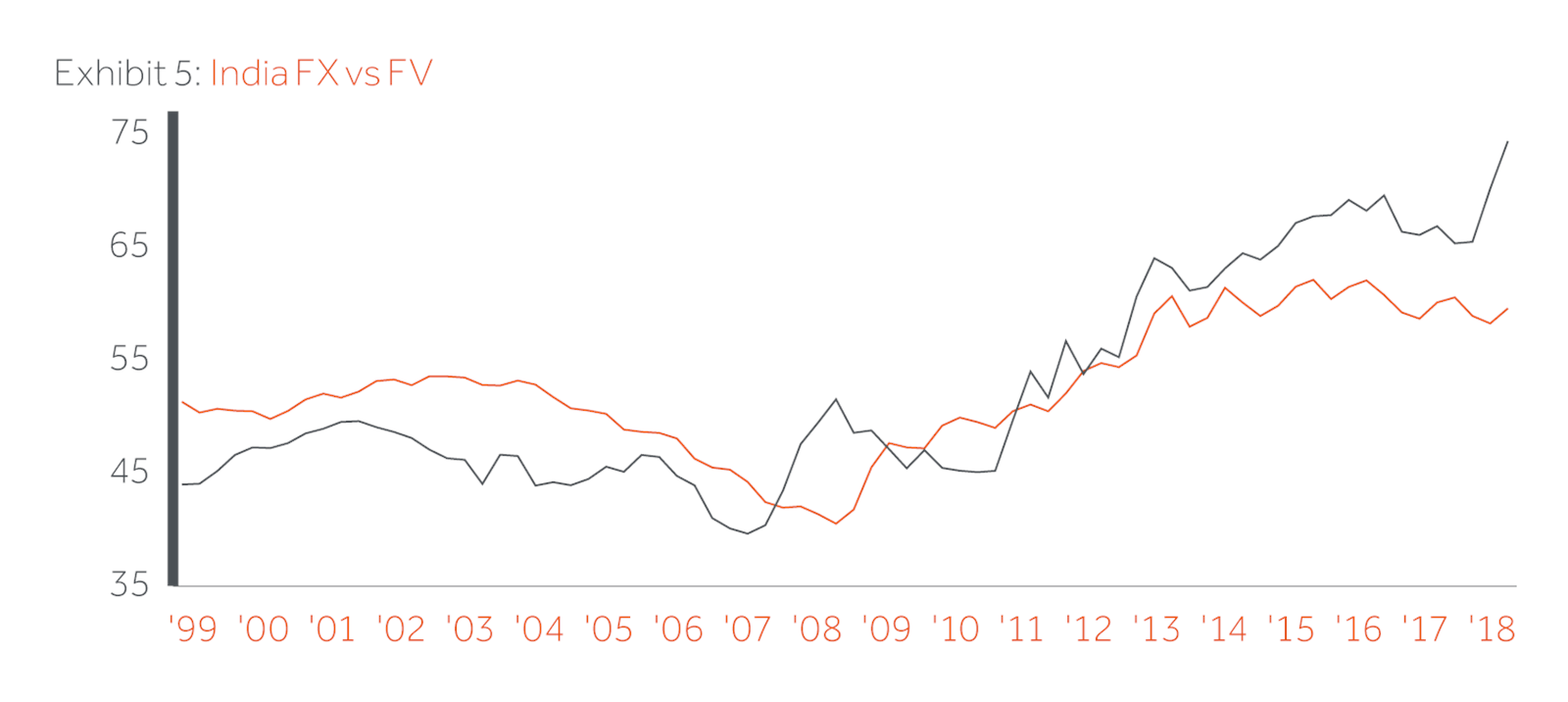

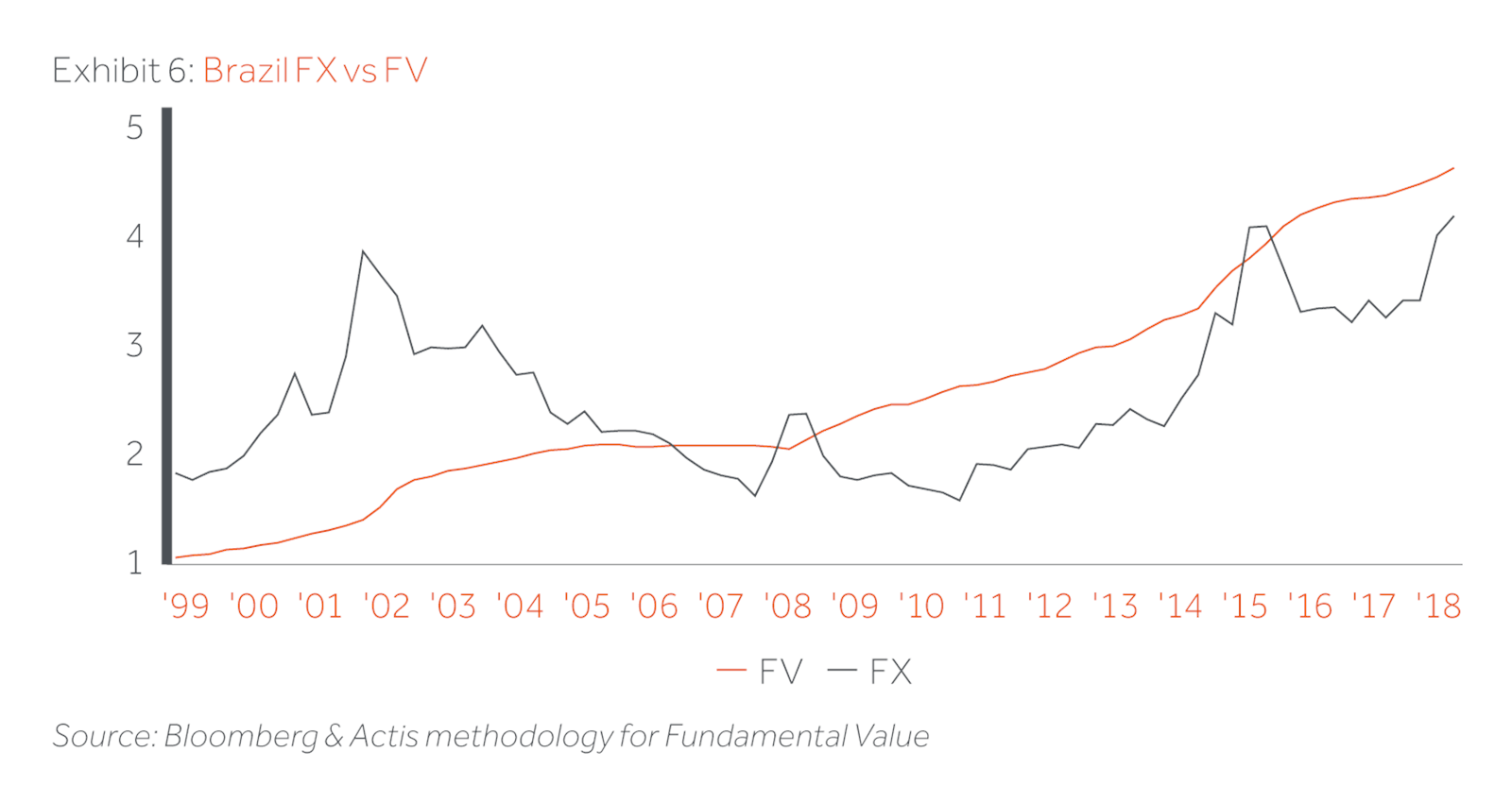

Our own measures of fair value have seen some currencies become less overvalued than last year. By contrast with a year ago there are an increasing number which appear quite undervalued including those of China,. India and South Korea. Among larger countries with seemingly overvalued currencies are Nigeria, Brazil and Kenya. Whilst our model is there to pick trends rather than timings, we would rather invest with a currency tailwind than headwind. Secondly Chinese US trade tensions have impacted investor sentiment around the prospects for world trade growth. In our October issue we featured an article written by Dr Ogus of DSG Asia on the background to and causes of trade conflict. Simon argued, and we agree that this is a multiyear issue as far as Sino US relations are concerned. A Democratic House of Representatives may also want to take a critical look at NAFTA 2.0 a treaty which at first sight is quite beneficial for Mexico.

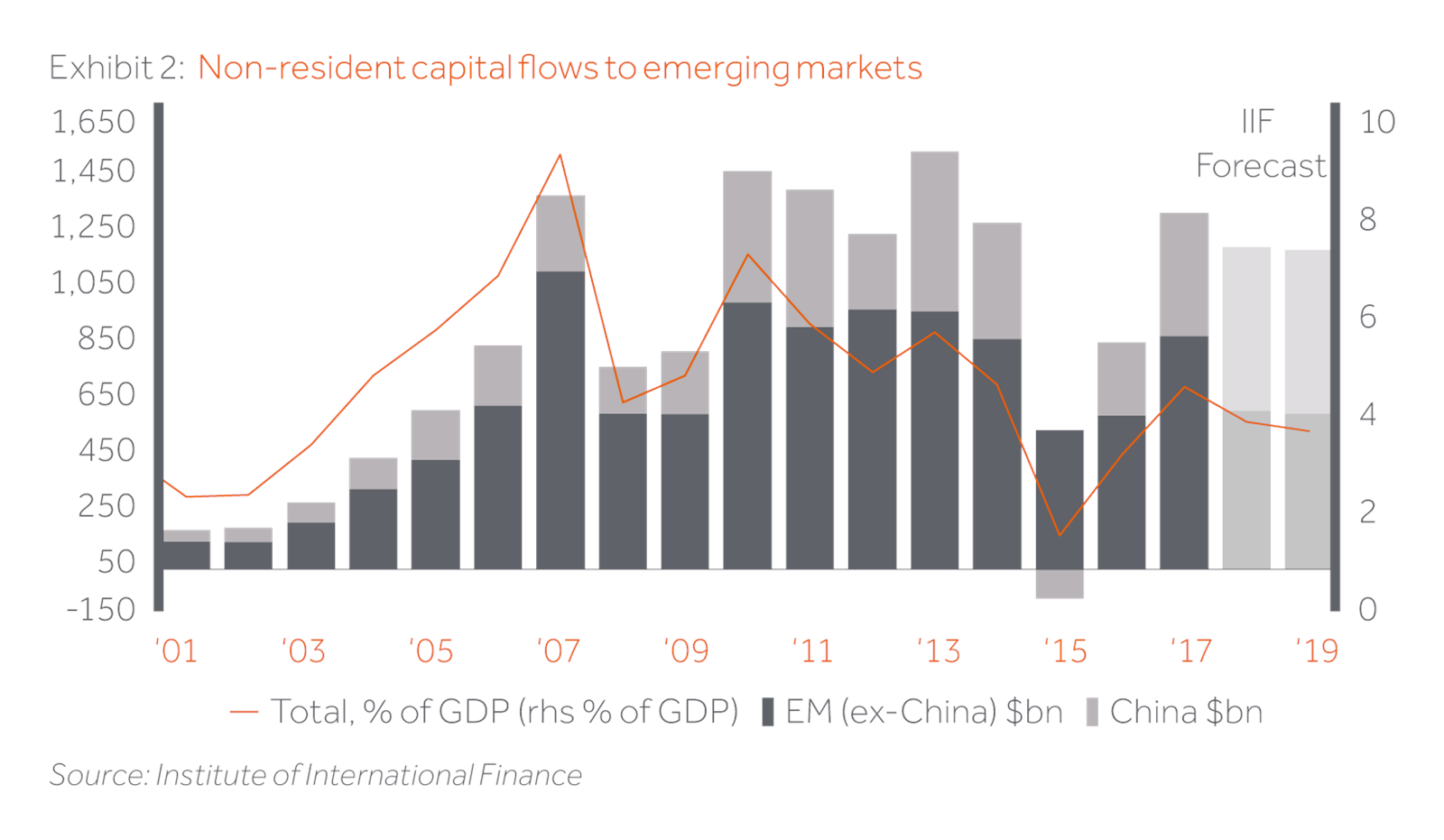

Given such headwinds and tumbling stocks, bonds and currencies one would have expected that cross border flows to Emerging Markets had plunged. Far from it -as of end October 2018 flows were largely unchanged year on year the Institute of International Finance calculates. This masks the fact that these flows have been dominated by increased exposure to China. Elsewhere inbound flows are down 30% reflecting portfolio reallocation and domestic capital flight. We suspect that much of this is simply a reversal of inflows seen in 2016/17. Whatever the cause the conclusion is simple: – EM countries are having to work harder to attract capital flow. As the tide swings from the quantity to quality of inputs, winning sectors will take increasing flows and countries that do not reform will find it harder to fund deficits. Long term domestic savings movements along with migrant remittance flows become ever more important in this environment.

Politics was a big focus in the last 12 months in Latin America with elections across the region in eight countries including Mexico and Brazil. We take a close look elsewhere in this edition at the elections of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and AMLO in Mexico. Both leaders successfully utilised social media to secure election and both have mandates to address corruption and existing business systems, At the same time both believe in central bank independence and have stellar economic leadership teams.

In 2019 the focus switches to Africa with elections in South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and a further 11 countries. These contests are being held after low or no growth in income per capita over the last 4-5 years which suggests that appetite for reforms and restructuring will be high. Elsewhere investors in India will be watching closely in the early spring as Narendra Modi runs for re-election. Elsewhere in this edition is a comprehensive guide to the what and where of 2019 elections.

Governments around the world tend to over promise and under deliver. In part, this stems from the different time horizons of structural reform payback and financial investors attention spans. The Thatcher revolution yielded increasing returns towards the end of her 11-year span in office rather than when first introduced. The same was true for President Reagan and supply side economics. In many EM countries however time is not an affordable luxury. We take a deep dive into the challenges facing South Africa as it heads into a crucial election next spring and conclude that righting the wrongs of the Zuma era is an essential but lengthy process. And our portfolio companies in Brazil and South Africa to take just two examples of difficult economies feel that a little reform can go a long way in helping their operations.

Whilst it is easy to be gloomy, we should remember that we are investing in companies and sectors as much as countries. In 2018 despite the election cycle we were able to successfully list Stone, a Brazilian payments business on NASDAQ in the second largest fintech IPO of the year. In South Africa despite economic challenges very successful portfolio exits have been feasible. The energy sector continues to provide excellent returns and investment opportunities as does renewable energy infrastructure. Opportunities in fintech healthcare, educational services and logistics align to our desire to invest in above average growth sectors which are contributing to increased economic resilience. A focus on improving governance and operational values is also very much part of the opportunity set. We have written about many of these themes in these pages and will continue to do so in 2019.

Any investment justification which uses the phrase ‘in the long term’ acknowledges as we do that the short term may be quite challenging. It is also worth recalling that history suggests the best time for EM investing is when currencies are down, and economies depressed. This is certainly true for the multiyear private market investment opportunities which form our opportunity set.