In the Middle East, infrastructure investment is a race to diversify away from oil and gas-driven economies. In Africa, infrastructure investment is a contest to keep up with population growth and the widening infrastructure gap. In both, the state is the key determinant of success, setting the rules of the game, deciding who participates, refereeing along the way and championing the results. Understanding these race dynamics through deep local networks is critical in targeting profitable and resilient infrastructure investments.

Middle East: Diversification-driven Infrastructure

The Middle East economic diversification effort has a new tailwind: the energy transition may reduce global demand for hydrocarbons well before the region’s resources are depleted.

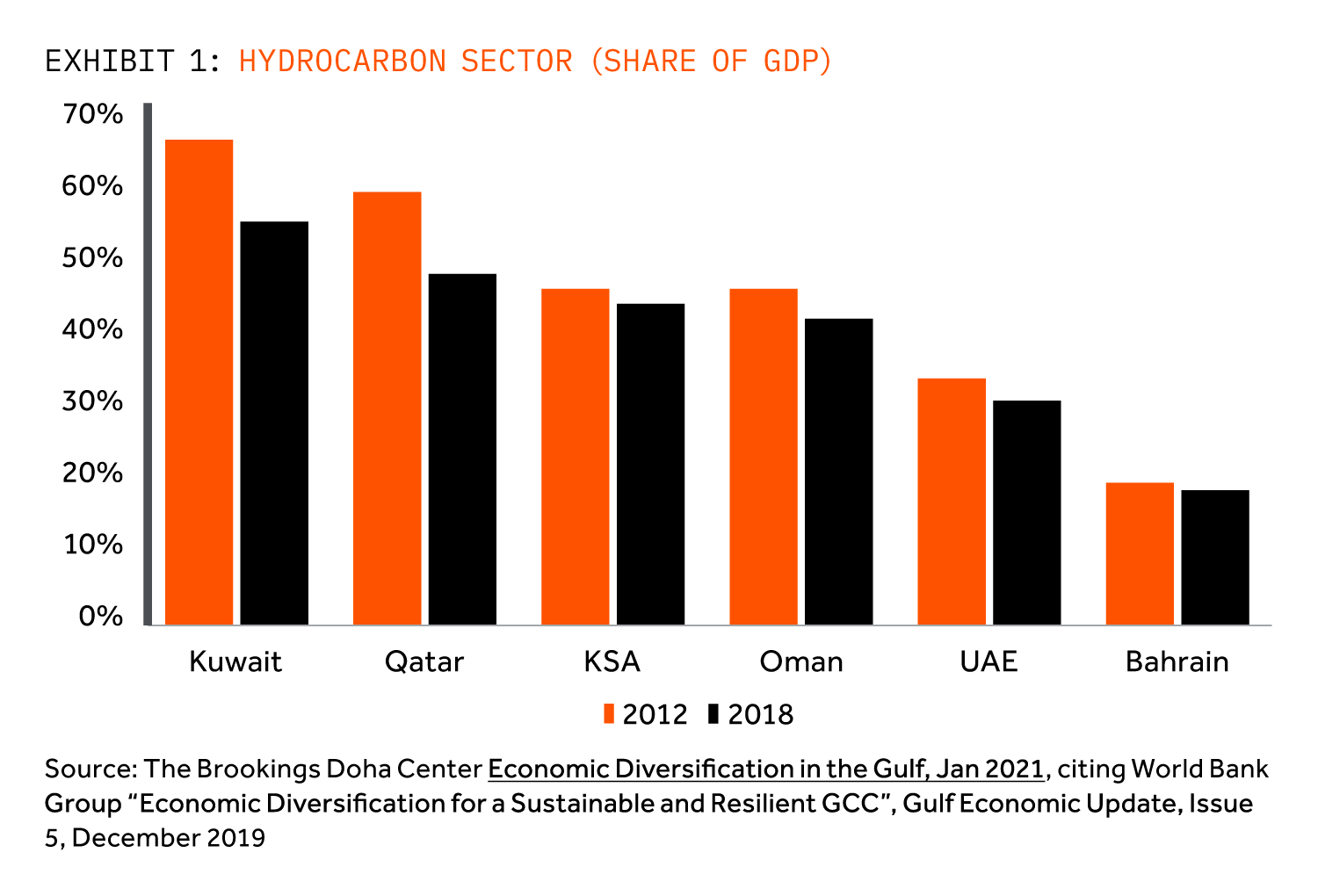

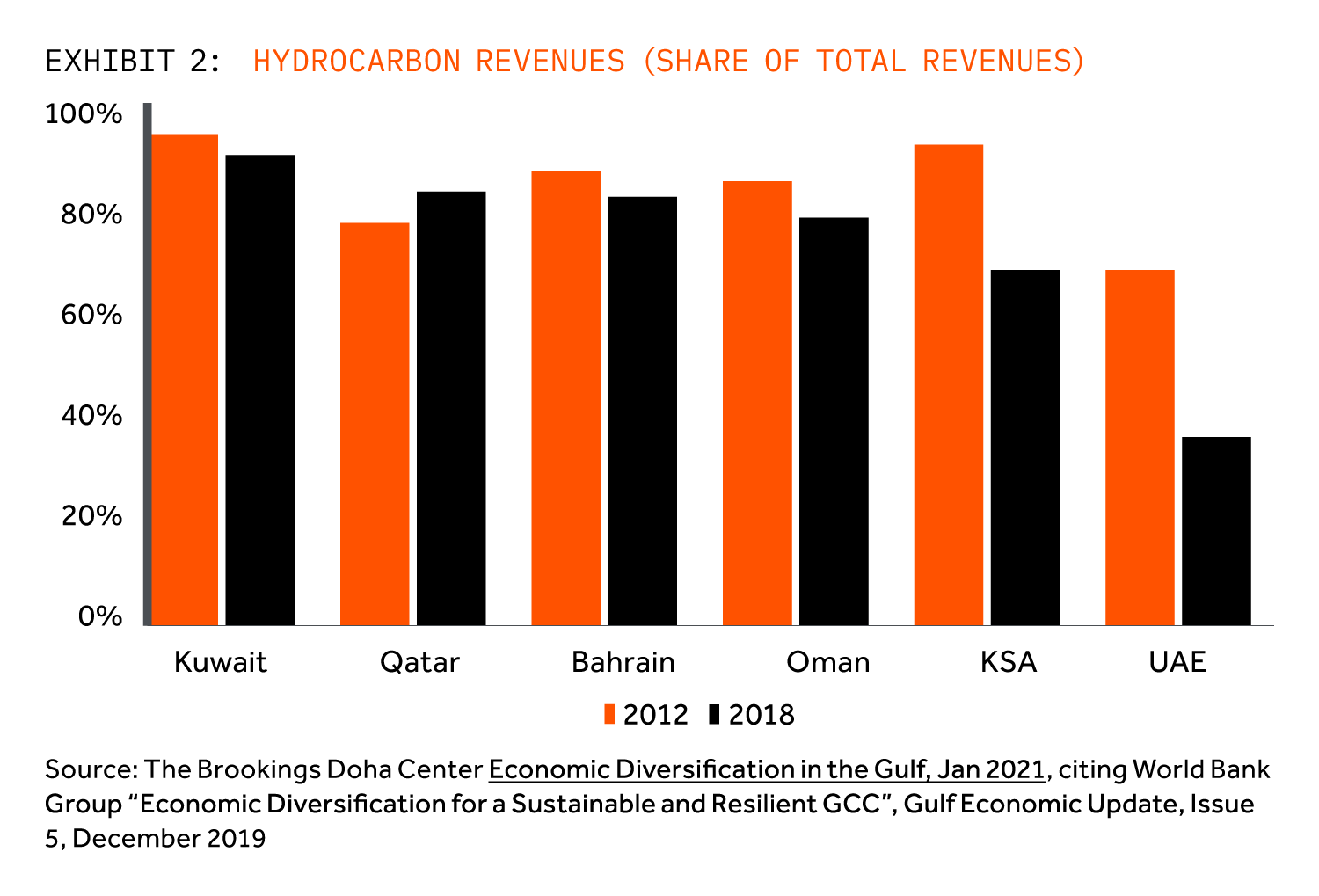

All GCC (Gulf Corporation Council) countries have long stated their focus on diversifying their economies away from natural resources, yet progress over the past decade has been modest. Oil and gas production still hovers around 40% of GDP for the region. This underestimates the economic impact of the percent of state revenues fuelled by oil and gas (70% for the region) that drive other sectors of the economy such as construction. Even countries with lower resource bases, such as UAE and Bahrain, still rely on oil and gas through transfers and spending from neighbours. UAE has made the most progress in diversification.

What is needed to achieve that true diversification is both policy change and infrastructure investment. This includes lifting lingering politically driven trade policies, and regulatory reform to allow more private sector participation into traditionally state-controlled sectors. In order to capture more of the cloud spending trend, a sector growing at 25% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) across the (GCC) countries, Qatar and Bahrain recently passed legislation to open up data traffic into and out of the country, allowing for data centre construction to service foreign markets. In the power sector we see some-and would like to see stronger-open access for private generators of power to be able to wheel power directly to end consumers and to offer commercial and industrial suppliers of power access to net metering, e.g. to sell excess power to the grid. Continued unbundling of the power sector could unlock significant flows of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the region into sectors that diversify the economies.

ENGAGEMENT WITH THE PRIVATE SECTOR WILL UNLOCK THE CAPITAL, ESPECIALLY ENERGY AND TRANSPORT

True diversification also includes physical regional integration such as cross border road connections and transmission lines to export the Middle East’s other natural resource, solar power, and new technologies including hydrogen. Transmission connecting countries in the region to each other, and then onwards to Europe, are in construction or planning stages, such as the 900km $1.6bn Saudi to Egypt line. This market development will support the goal that Saudi Arabia announced at the end of 2021: to spend roughly $100bn on renewable energy and $115bn on transmission by 2030, in order to reach its stated goal of Net Zero by 2060, and provide significant investment opportunity across the value chain.

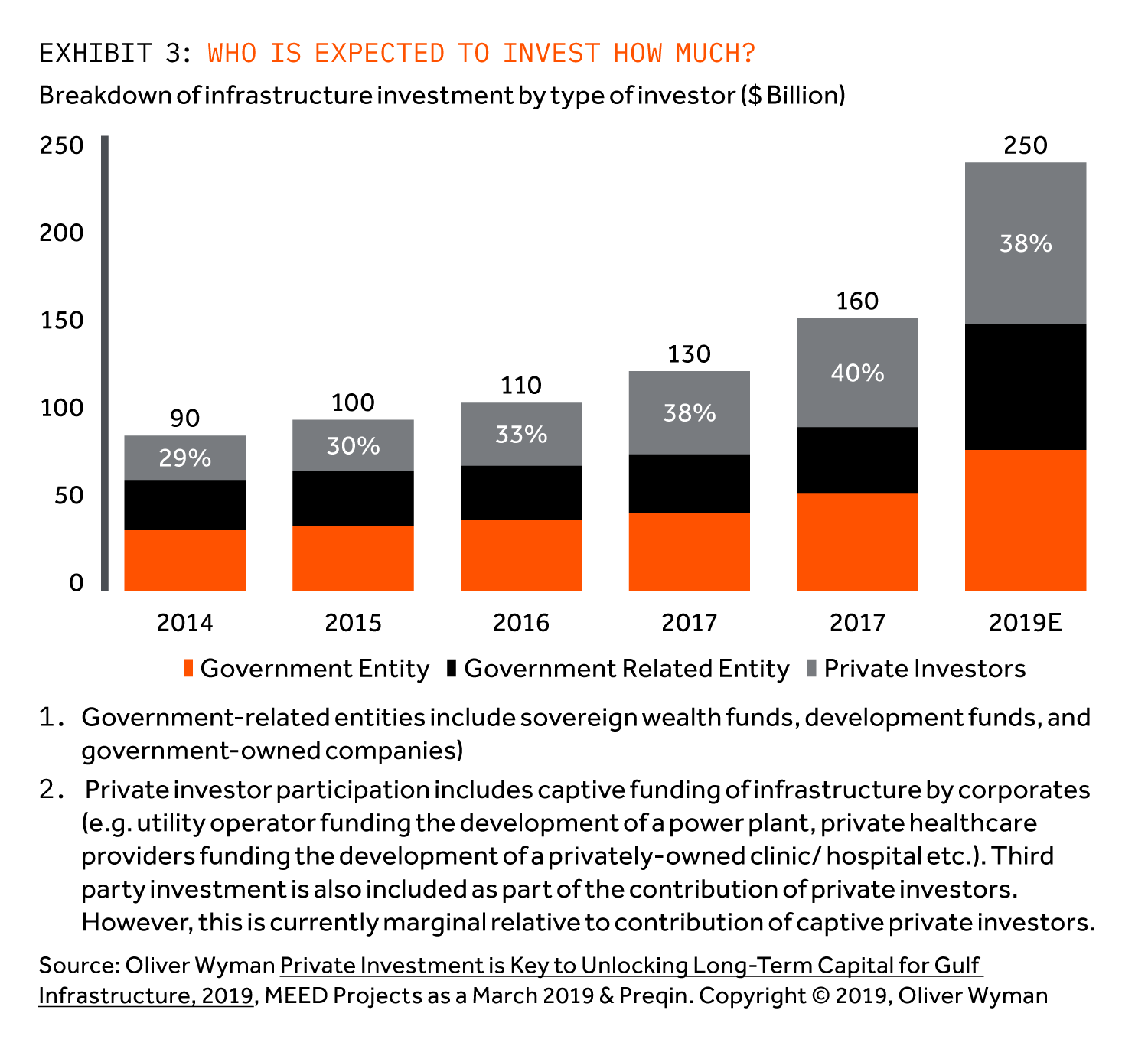

The region’s infrastructure investment requirements to meet these demands will not be funded from government entities alone, and as per the chart below, the role of the private sector has been increasing and is expected to increase both in scale and percentage going forward.

Enabling Africa

The impetus for sustainable economic development in Africa is heightening. Population is projected to almost double from 1.4 billion to 2.5 billion by 2050 and rapid urbanisation – African cities will account for 39% of the world’s urban growth —are critical drivers. They put further pressure on the need to close the infrastructure gap, optimise growth potential, boost productivity and create jobs for its teeming population. Weak infrastructure shows in high production costs whilst competitiveness issues are reflected in low power provision – about 40% of the population has access to power. A lack of effective transport infrastructure to support cost effective distribution of goods and services also hurts.

Pre-pandemic, Africa’s 10-year average GDP growth of 3.9% was slightly higher than the global average of 3.7%. However, its per capita growth for the same period trailed significantly at 1.2% compared to 2.5% for the global average. Africa already accounts for 75% of the World’s poor – living on below $2 per day. This will grow if the infrastructure challenge is not addressed.

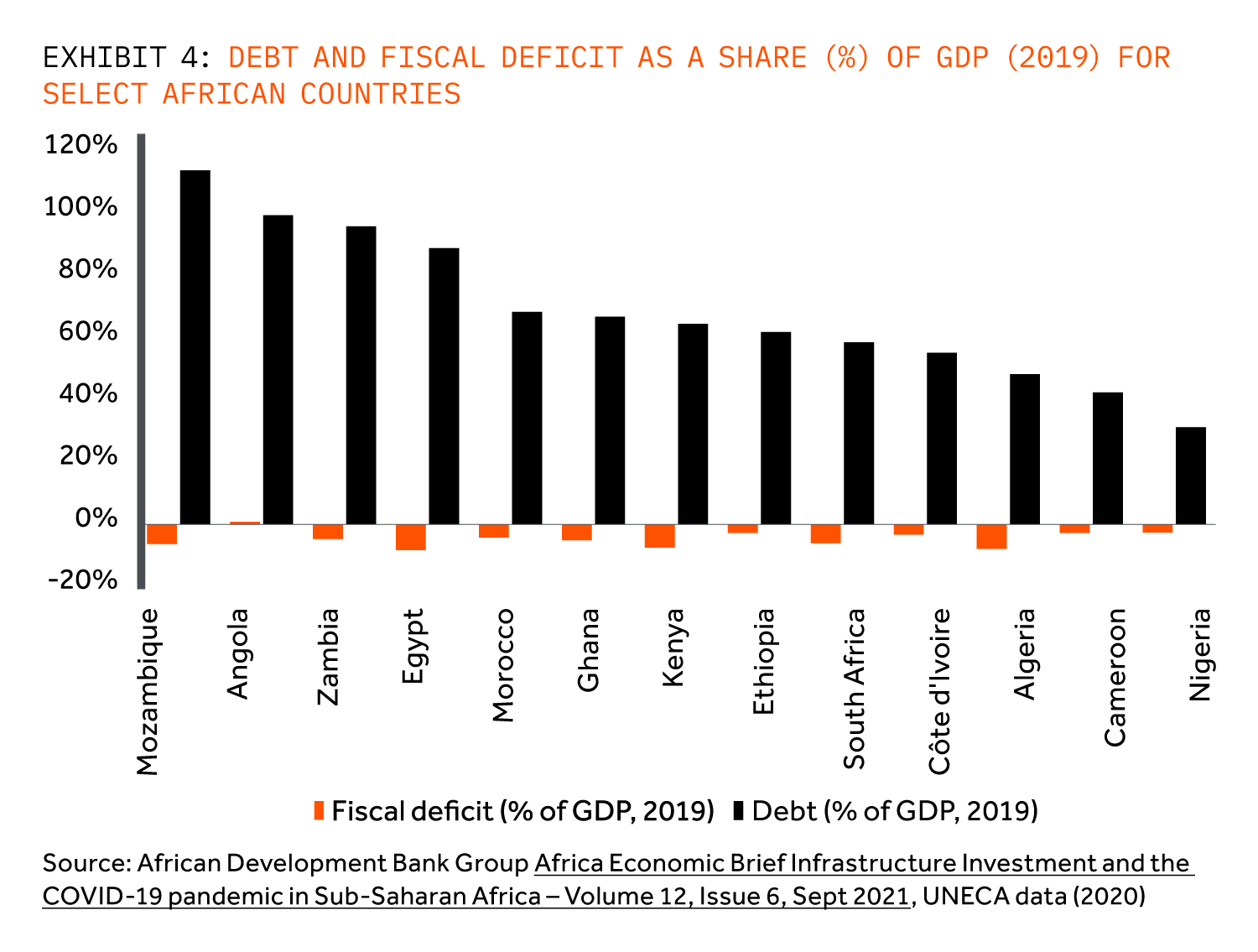

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the already strained capacity of African governments to fund key infrastructure, worsening their stressed fiscal positions with rising debt levels and widening deficits. Exhibit 4 indicates the position pre-pandemic of debt-to -GDP ratios (%) which was already quite tenuous with minimal borrowing capacity and fiscal deficit (%) already exceeding 3% by most countries. The debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated by UNECA to have increased by 10% post pandemic. State-owned enterprises have been similarly hit, most notably Eskom the integrated power utility in South Africa.

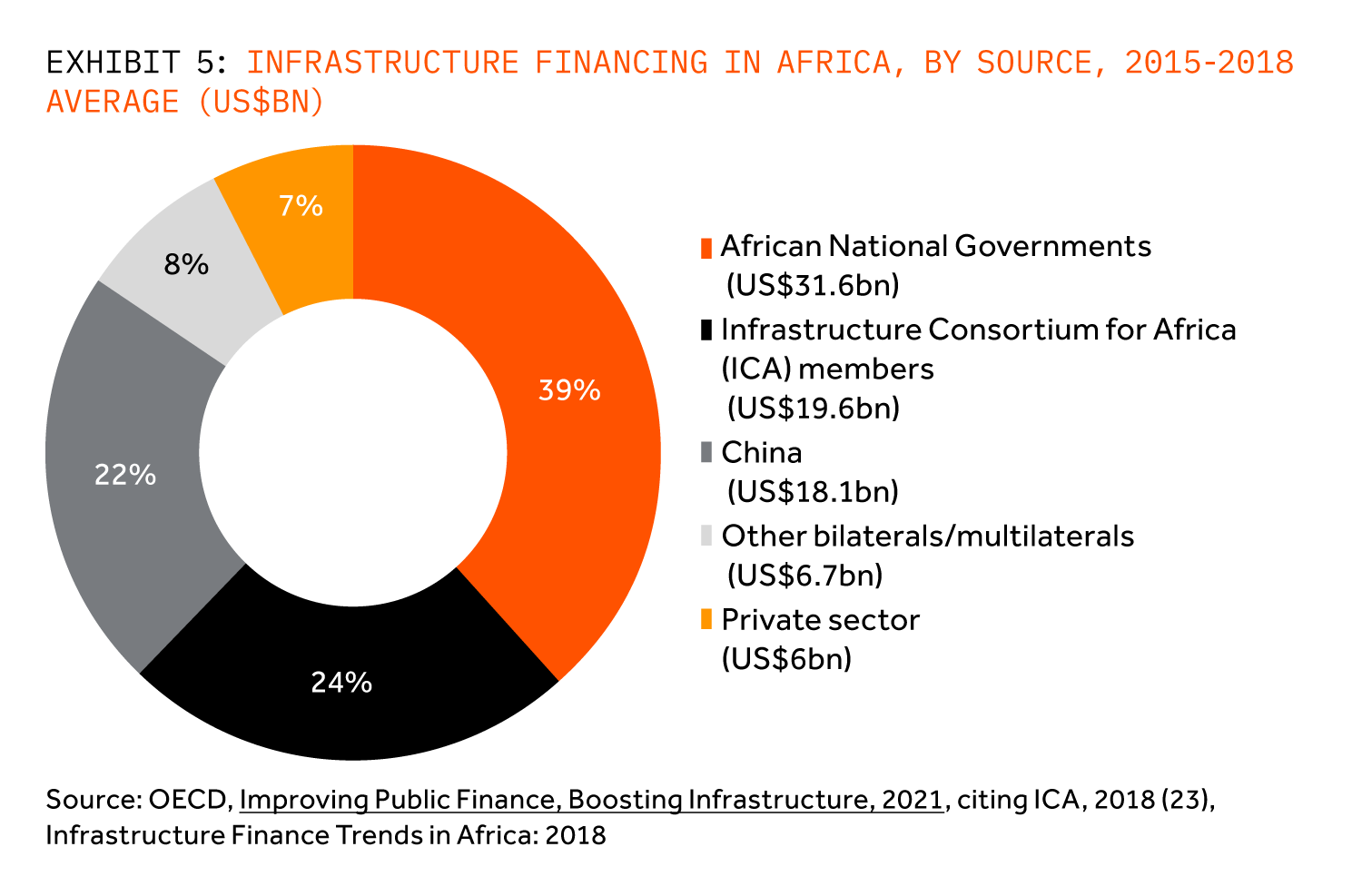

African governments remain the largest investors in its infrastructure; funding 39% on average between 2015 and 2018 in Exhibit 5. The other main investors are multilateral agencies at 24% and China at 22% the largest single bi-lateral investor to African infrastructure. Private sector funded only 7%. Chinese appetite for African investment is waning. Following the continent’s debt strain and a number of defaults, President Xi announced in November 2021 that China will reduce its funding to Africa by 30% and move away from largescale infrastructure and into SMEs and other smaller scale investments. COVID-19 has also resulted in lower appetite of the private sector to invest in Africa due to the rising uncertainty arising from lower commodity prices – though this has abated, worsening fiscal deficits of the governments and the sustainability of the rising debt remains a concern. The chances of Africa reaching the annual need for $150bn of infrastructure spend are receding barring material change in incentive structures.

AFRICAN GOVERNMENTS NEED TO DEEPEN ENGAGEMENT WITH THE PRIVATE SECTOR TO PROVIDE AN ENABLING ENVIRONMENT TO INVEST

African governments need to deepen engagement with the private sector to provide an enabling environment to invest. Another major identified constraint to investment in African infrastructure has been the dearth of bankable projects – only 20% of projects move past prefeasibility and only 10% to financial close. Engagement with the private sector on the required risk mitigants and guarantees should help unlock capital for projects, especially in energy and transport sectors that are deemed commercially viable and could be funded exclusively by the private sector with appropriate political risk mitigants and revenue guarantees. This will allow governments to fund the infrastructure sectors, such as waste and water, that are less commercially viable though just as critical to the overall wellbeing of its populace.

Political will and focus are key to driving infrastructure investment. In 2014 President Macky Sall of Senegal announced the Plan Emergent Senegal, a medium term $20bn investment plan to stimulate growth. Ambitious investment conferences and headline-grabbing proclamations of stretch goals are quite common on the continent, however President Sall’s executive focus and systematic removal of roadblocks to infrastructure projects has been unique and critical for success of the program. The Plan and its progress is tabled regularly at Cabinet meetings for review. He set up an office to oversee the plan, with leaders who could pick up the phone to Ministers and discuss issues on strategic projects, including airports, trains, roads, ports and power plants, cutting through the inefficiencies that often lead to the slow demise of nascent infrastructure projects. When Actis portfolio company Lekela was finalising the development of the Taiba N’Diaye wind project, one of the power projects identified as a priority under the Plan, this office and the clear political focus on the Plan was instrumental and was an attractive reason the company invested in the first place.

Though a smaller economy, Rwanda has similarly taken bold steps to increase public investment in infrastructure, spending more than its East African neighbours at 13% of GDP on average the past five years. More is needed, but as Rwanda is finding, similar to many African nations, that it cannot finance further from public funds and hence needs to move beyond the slow-moving public-private partnership (PPP) model to a purely private sector model to facilitate greater FDI into infrastructure, specifically power and social housing. Rwanda is indicative of its region: while Eastern Africa has 36% of Africa’s population, only 20% of the continent’s infrastructure spend occurs here, and with sovereign, bilateral and multilateral investments unlikely to increase, the gap must be met by the private sector. It is the government’s role to facilitate this.

Across Middle East and African countries whilst scale, drivers, investors and policies range, the threads are the same: infrastructure needs are growing, and state balance sheets are stretched and hence private sector investment in infrastructure is sought. Governments and policy-makers will drive the direction and opportunities, and hence investors need local presence and intelligence to choose wisely and opportunistically.