“The greatness of a nation lies in its fidelity to the constitution and the strict adherence to the rule of law.”

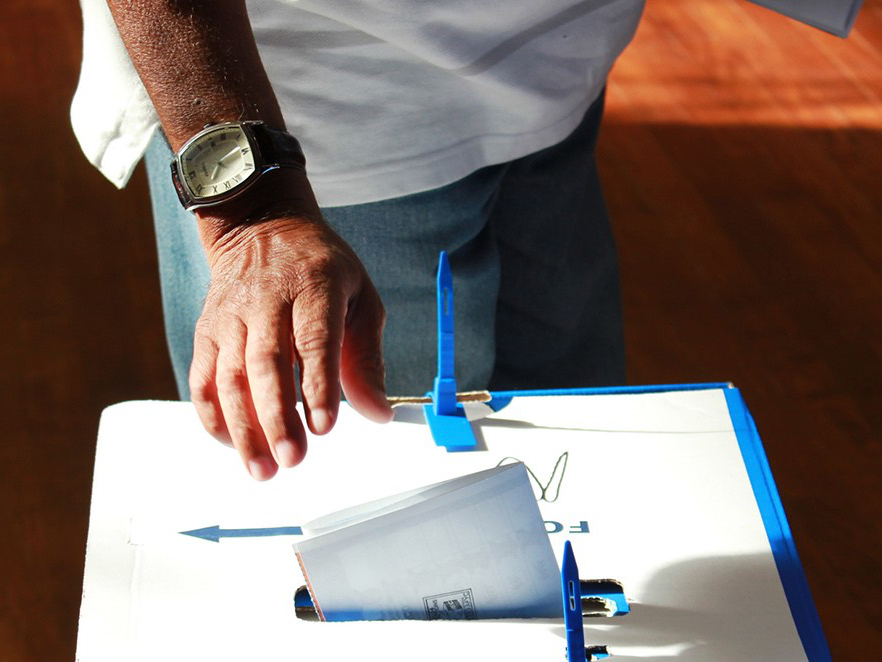

Kenya’s chief justice David Maraga teed up a re-run of the presidential elections when he announced on September 1st that “irregularities and illegalities” in the transmission of the results rendered last month’s poll invalid. New elections must now take place within 60 days.

The race was already a Kenyatta vs Odinga re-match. Opposition leader Raila Odinga, now 72, first contested the presidency ten years ago against Mwai Kibaki, an electoral defeat followed by widespread violence and bloodshed. He came back in 2013, standing against Uhuru Kenyatta, when after a second defeat, an appeal seeking to overturn the result was filed with the Supreme Court and swiftly dismissed.

The 2013 elections were the first held under the new constitution and the first run by the new Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). In 2013, Kenyatta won with 50.5% of the popular vote, this time as the incumbent, his Jubilee party “won” 54% of the vote. Markets reacted positively to the preliminary result and to the re-election of Kenyatta, rallying to a near two year high, and initially at least, most observers believed Odinga’s petition would fail in the same way as in 2013.

The unexpected judgement, described by The Economist as “an astonishing decision”, prompted hyperbolic headlines (although little actual impact) around the markets in the immediate aftermath:

- trading on the local Exchange was suspended for 30 minutes after foreign investors, attempted to block sell their shilling assets;

- yields on Kenya’s foreign debt climbed the most in almost two months according to Bloomberg with the $2 billion of Eurobonds due June 2024 soaring 21 basis points, the most since July 6, to 6.23%; and

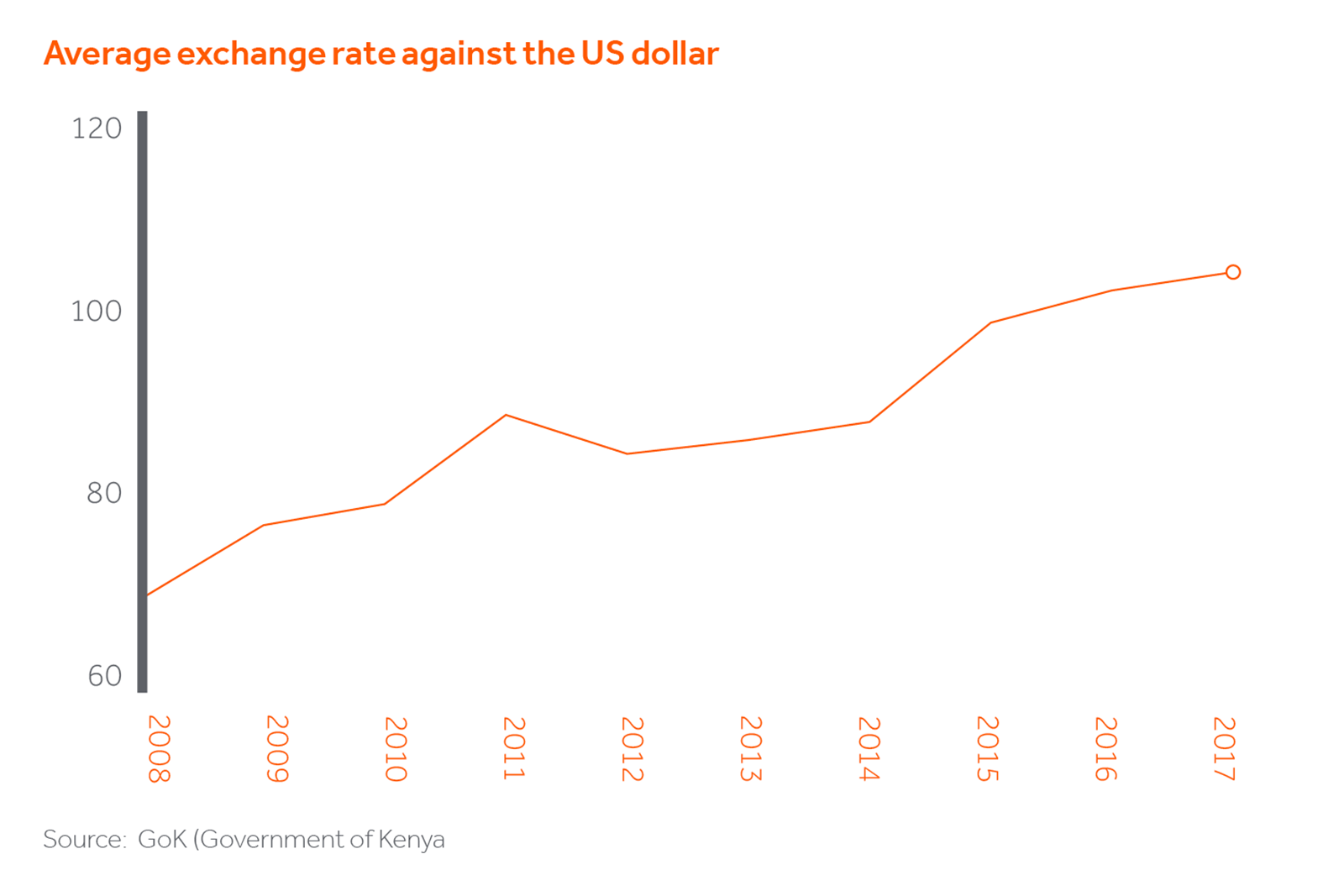

- the Kenyan shilling fell by 0.4% within an hour… but swiftly recovered.

The September ruling was unprecedented in Africa, and Kenya now joins a very small group of countries including Maldives and Austria where in recent years the courts have overturned the will of the people on legal and administrative technicalities.

Despite the short term fallout following the announcement, the ruling has been lauded as an important landmark for democracy and governance. It has been more than seven years since the new Constitution was adopted in August 2010, and it seems to have passed this stress test. Looking back to the trauma of the 2007 elections, it is also reassuring that it has proven possible to contest a result without provoking immediate violence and civil unrest.

The Supreme Court judgement was particularly damning of the IEBC, stating that the body had “failed, neglected, or refused to conduct the presidential election in a manner consistent with the dictates of the Constitution.” There will be a more detailed assessment following the judgement but this leaves the IEBC and the country in a sticky situation- it will be difficult to press ahead with new polls with certain key senior figures potentially facing criminal charges. This impending delay will also impede important decisions and discussions in particular around changes to the interest rate cap – the limited availability of credit in the banking system that has followed the imposition of this cap is widely seen as a material constraint to further economic growth.

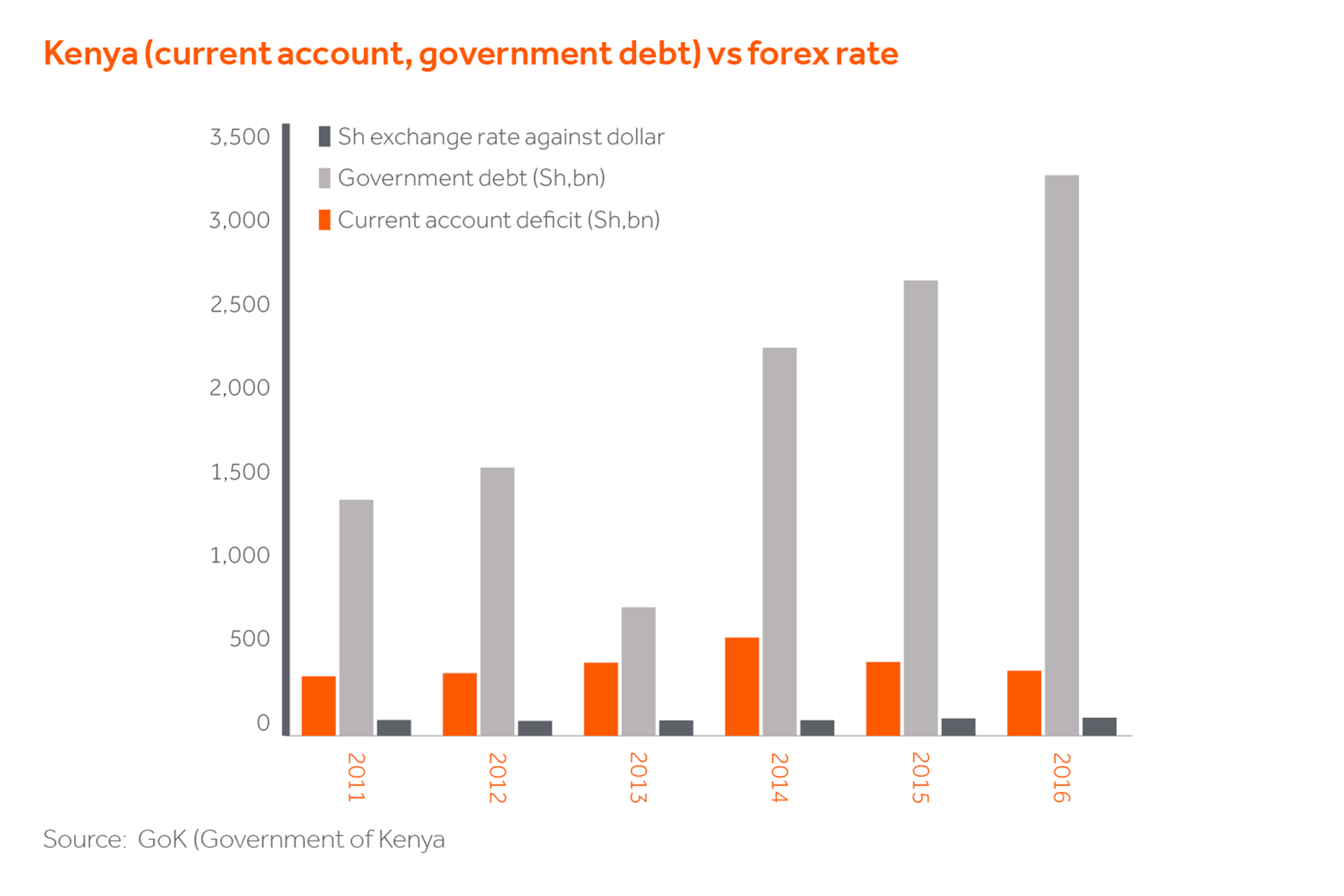

In terms of the direct costs to the economy, the cost of the first election was reported to be around US$500m, some portion of which will now be re-incurred. However, there is another fiscal implication to consider – a re-run of the race means more campaign promises. The manifesto pledges in the August elections already included expensive crowd pleasers like increasing public sector wages (up 17% year on year by June 2017) or large scale infrastructure projects that looked set to push up Kenya’s US$4.5bn budget deficit.

Debt levels are generally seen as dangerously high and a slowdown in corporate earnings and tax revenue collection has put further pressure on the Government’s ability to service the national debt. Prior to the election, the Government had made progress in reducing the deficit to single digits as a proportion of the national income from the double-digit levels common in periods prior to 2015. Before the elections, the Treasury had also committed to curtail overall public spending as part of reducing imports to keep the current account deficit stable.

What promises we can expect now remains uncertain, but both candidates will certainly be looking to improve from their current levels of support, and the temptation to make expensive campaign promises will be hard to resist.

Kenya has been a leading light in East Africa of late, and had been forecast by the IMF to grow GDP by more than 6% this year. It remains to be seen if these figures still add up – the economy is vulnerable – agriculture is a major source of employment and the country’s largest sector, accounting for 25% of GDP and roughly 50% of export revenue. Tourism contributes another 10%, and post-electoral uncertainty could well impact on tourist arrivals. From what we see on the ground, we already know that growth has slowed markedly in Q3, and we anticipate that this will continue into Q4, making the earlier estimates of 5-6% annual growth a difficult target to achieve.

So from our perspective, how does the election result change our view on Kenya? On the one hand the ruling can be seen as a longer term victory for democracy and governance in a country where historically regime changes have suffered either from accusations of impropriety or from periods of extreme civil unrest. On the other hand, even if the final electoral result seems unlikely to change, key decisions in the medium term are now going to be subject to delay, and this may well threaten the continuation of the path of improvement and growth we have seen in Kenya in recent years. We will be keeping fingers crossed for a peaceful outcome, independently of which candidate is finally elected.