The West often finds Iran hard to understand – a revolutionary theocracy yearning for an Islamic past, yet at the same time an educated society able to develop an indigenous nuclear programme in the face of forty years of sanctions. As tensions mount in the Gulf, how events turn out will rely to a large extent on how the Iranian leadership in Tehran sees the world. In common with the importance placed on understanding the “street view” in markets in which it invests, Actis believes that looking inside out often makes more sense than relying on the view from afar.

The US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) followed by additional sanctions targets structural and behavioural changes beyond restricting the Iranian nuclear project. Iran must counter this or risk losing influence in the region which it sees as vital for her security. If Iran fails to keep China, Russia and Europe onside, the JCPOA UN sanctions that were lifted as a part of that agreement would snap back into place. This could well lead to a long-term stand-off with the US risking economic collapse which will bring about the same result and provoke internal instability.

The situation is finely balanced: Iran’s current policy choices threaten to push France, Germany and UK (E3) towards the US position. Tehran calculates that recent meetings and the promise of further dialogue will be enough to prevent that for now. China and Russia will resist moving to the US position for wider geo-political reasons.

A SWOT analysis, as seen from an Iranian perspective and data on the economic realities highlight some interesting policy options.

Strengths

Iran is big, as big as the UK, France, Germany and Italy combined. Its population is approximately 82m, similar to Germany, but with a much younger profile with 50% of the population under 30. Iran sees itself as the natural regional leader.

Leadership of the Shia world-Iran is one of the few majority Shia countries in the world (Iraq being the other big one) and is the avowed leader and supporter of Shia minorities all over the Muslim world. These minorities are Iran’s natural allies, which Iran can use as proxies to destabilise Sunni-led countries which oppose it.

The Shia crescent– Iran can send men and materiel overland on the route Iran-Iraq-Syria-Lebanon in order to supply its most effective, and oldest, ally, Lebanese Hezbollah, as well as reinforce the Syrian regime and influence Iraq.

Internal stability – The émigré opposition have almost no support inside Iran, and domestic opposition is contained and suppressed by the security forces. Divisions of view between ‘hardliners’ and ‘moderates’ in the ruling elite will disappear if the regime is under threat.

The nuclear programme– In the long term a nuclear weapon will ensure Iran is never defeated militarily like Iraq and Libya. Even reaching the stage of nuclear ambiguity would be a safeguard against a US attack. North Korea stands as an obvious example of this belief.

Oil– Iran has about 10% of the world’s proven oil reserves.Energy is cheap, and hard currency earnings from oil exports make Iran’s economy potentially strong.

The IRGC and hybrid warfare– Iran has developed a range of aggressive techniques and tactics just short of conventional war which make it a regional power. Examples include cyber, use of Shia proxy groups (in at least Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, Lebanon, Iraq and Syria), missiles, drones, special mines, small boat swarm tactics.

Weaknesses

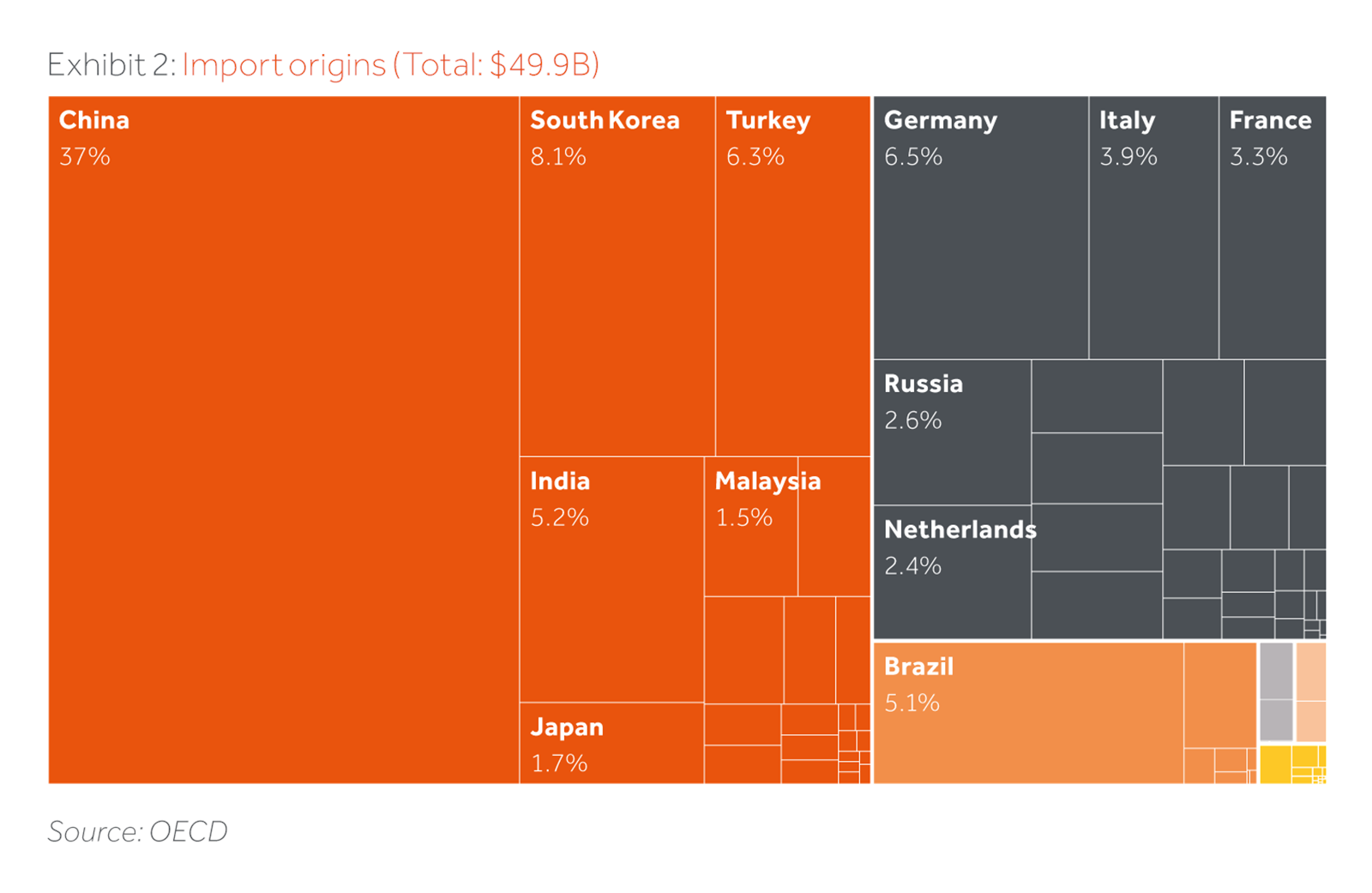

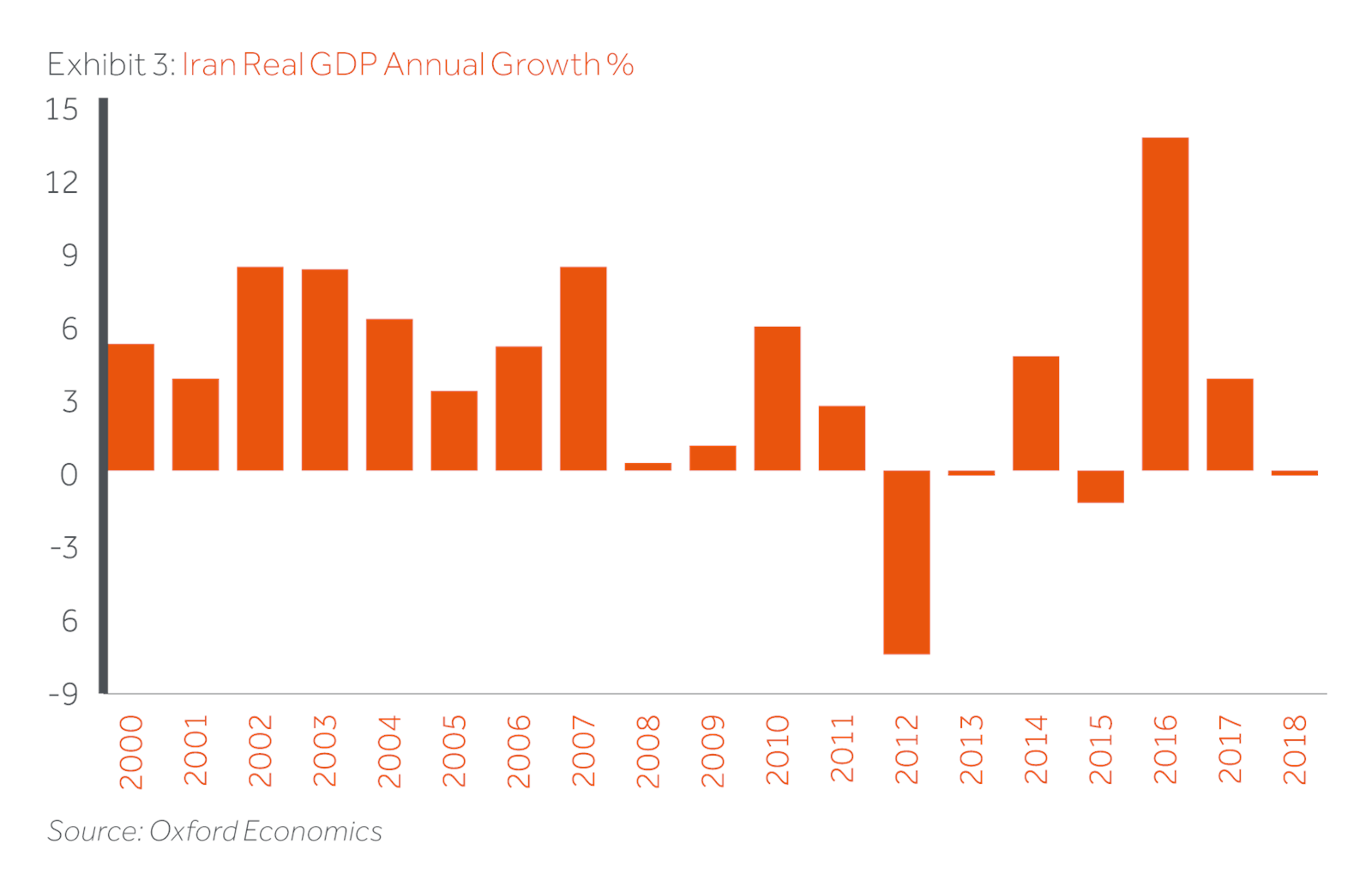

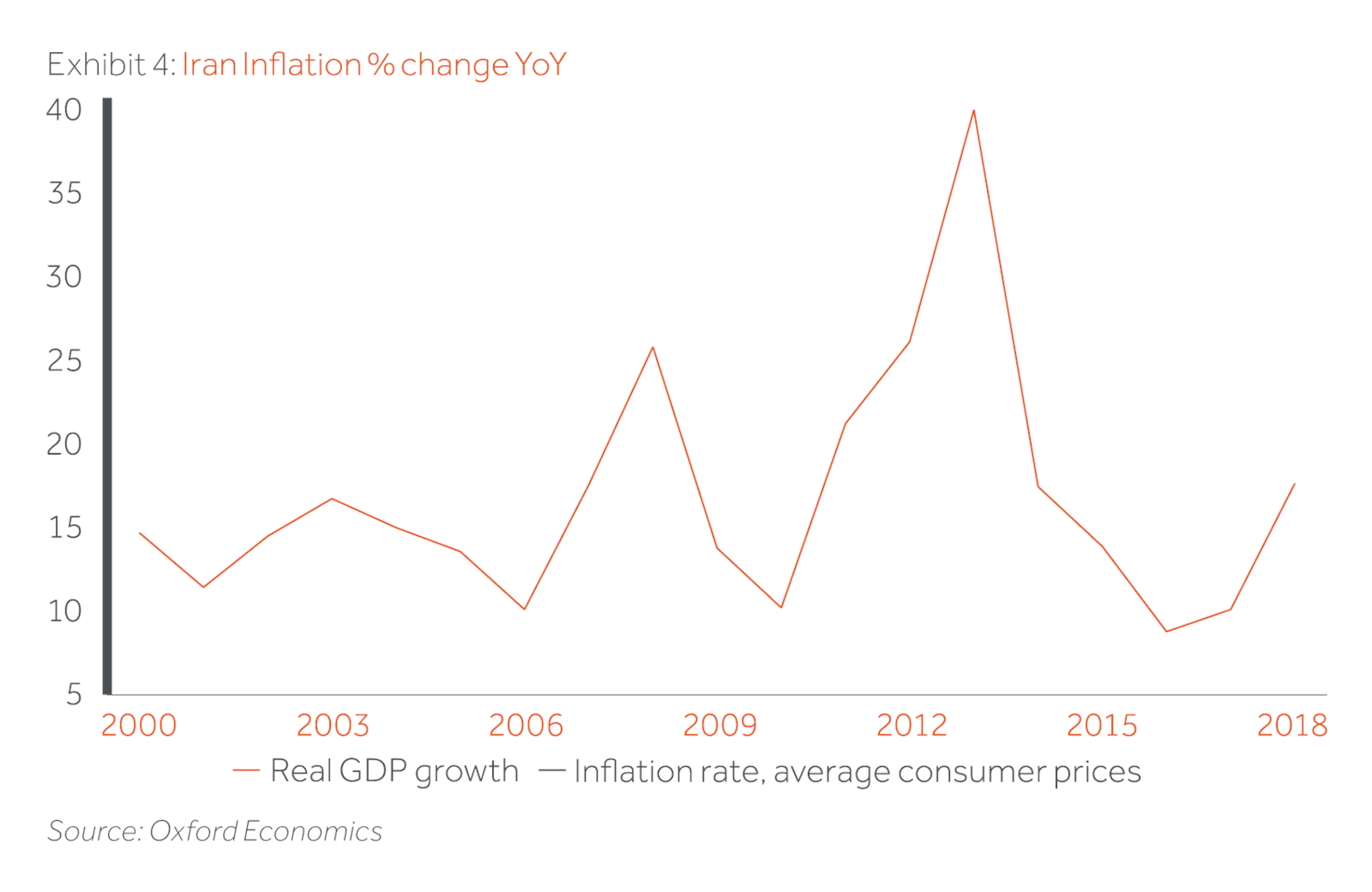

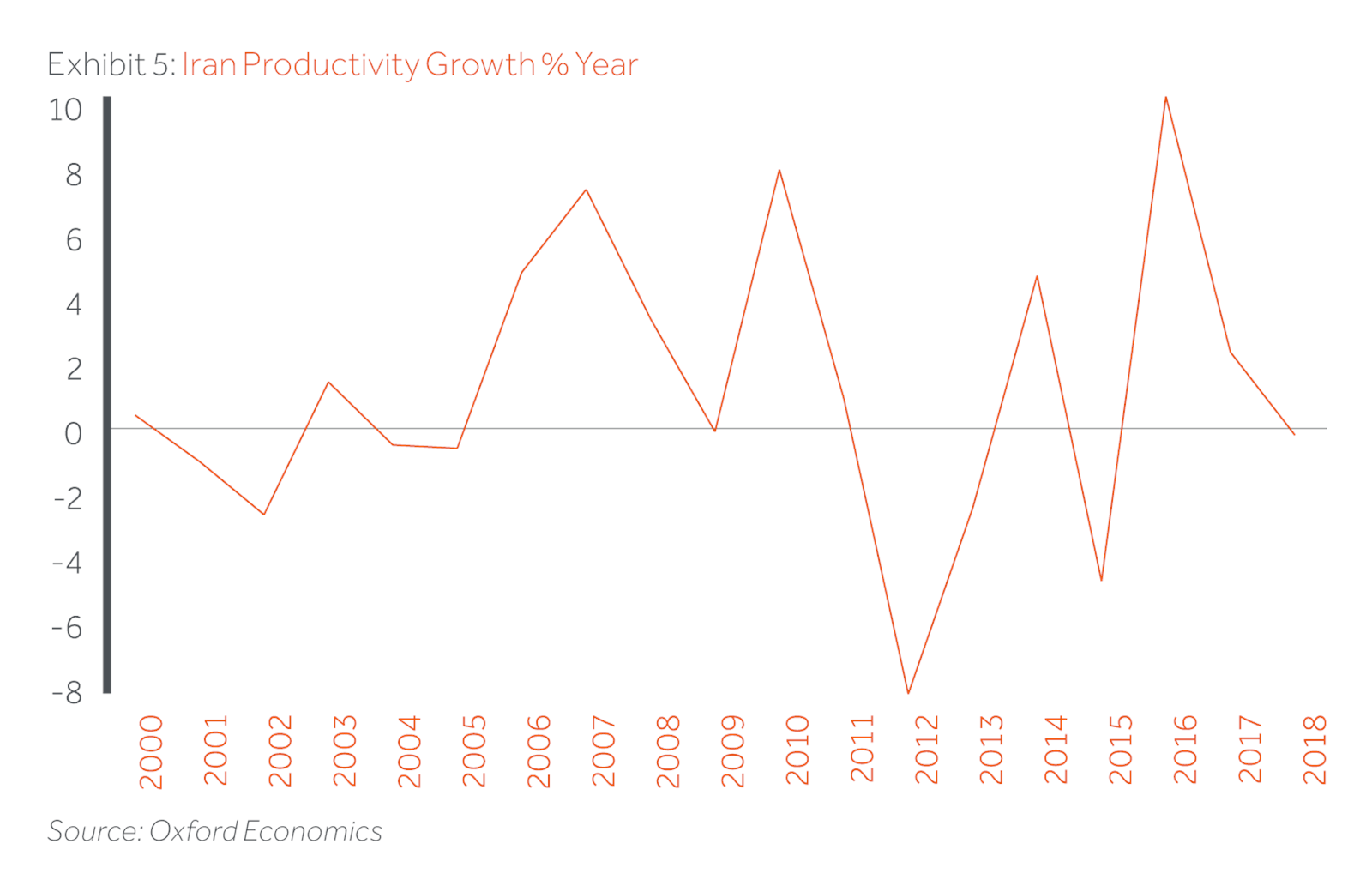

The economy– has tanked, largely as a result of sanctions. The latest US measures have had a severe effect, targeting corporations that have significant trade with Iran, including in oil and banking. Many Western companies have shelved investment plans for the foreseeable future, whilst China is attempting to focus on domestic companies with no US exposure. Total, for example, reluctantly scrapped its investment in the South Par gas field, its position being taken by CNOOC.

Historical sanctions have cut the economy off from international debt markets leaving low levels of overseas debt. Overall debt to GDP is a modest 35% which is likely sustainable given limited levels of government spending (25% of GDP), domestic financial repression and fiscal inflows equally balanced between oil and non-oil revenues. But there is limited room for anti-cyclical deficit spending which leaves the door open to internal unrest, particularly in a scenario where the economy contracts in line with IMF projections.

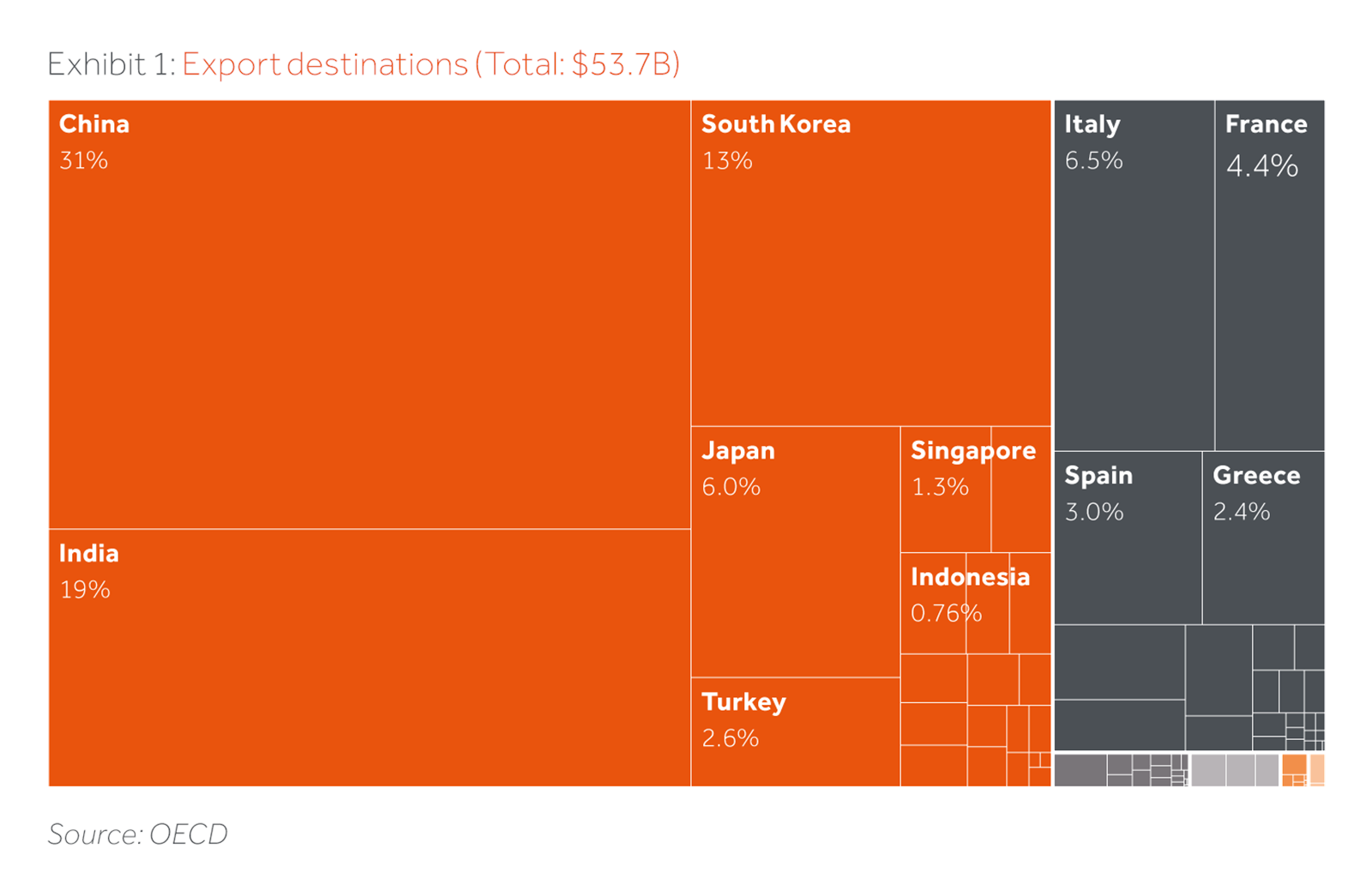

Like much of the Middle East, Iran has seen China and India as their main growth customers for hydrocarbons, but with wide ranging Chinese imports from consumer goods, to railways the domestic economy has seen little diversification away from oil and its derivatives

Lots of enemies and no strong allies– Iran is seen as a major threat by most of its neighbours, particularly the Gulf Arab states. It has no big power ally – although China and Russia have interests in Iran, they were both full signatories to the Iran nuclear deal and both see radical Islam as a threat. Iran’s only full ally is Syria.

Weak conventional defence forces – Although Iran has bought arms from Russia and China, Iran’s defence forces cannot take on the US using conventional means.

Opportunities

Divide the West– If the US is isolated it will be hard for it to attain its goals except through very unpopular direct military action.

Get closer to Russia and Turkey– Russia and Iran are on the same side in Syria, where Russian intervention shows how far Putin will go to thwart the US.

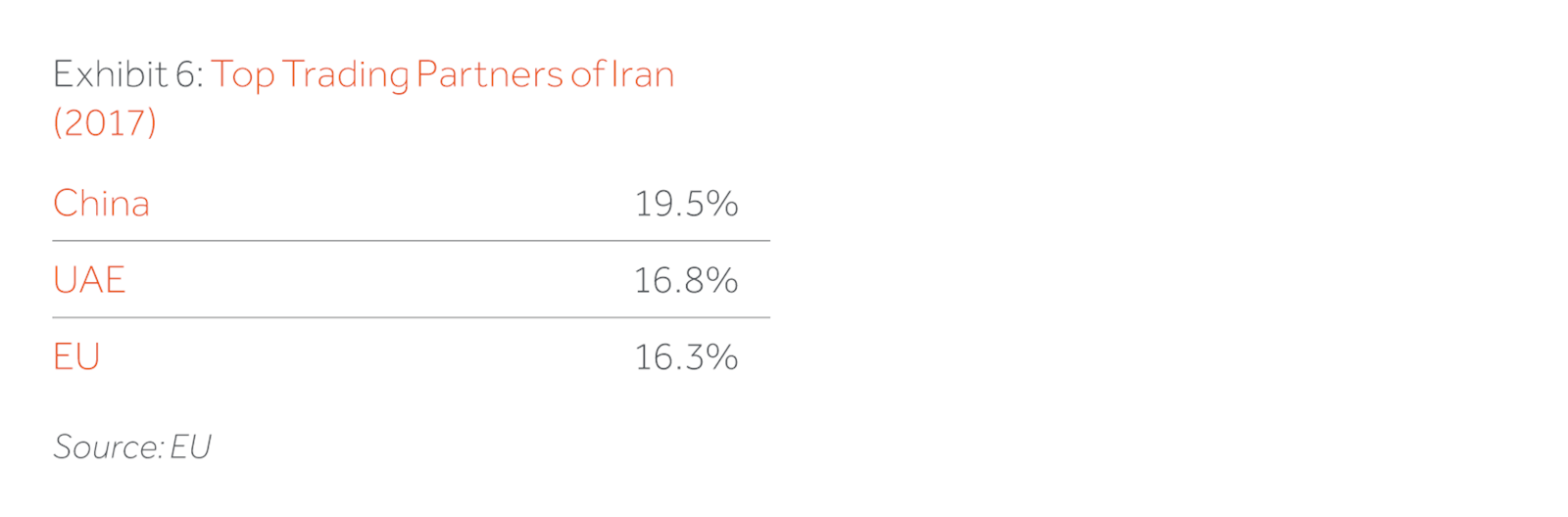

China– China sees Iran, with a deep history of trade, as a long-term link for Asia to the Persian Gulf and onwards to Europe. It will oppose US military action against Iran but will not act as a guarantor of security.

Threaten the GCC countries– Destabilise the UAE economy or attack the Saudi oil economy through proxy terrorism. The IRGC has threatened to escalate violence across the region if Iran is attacked.

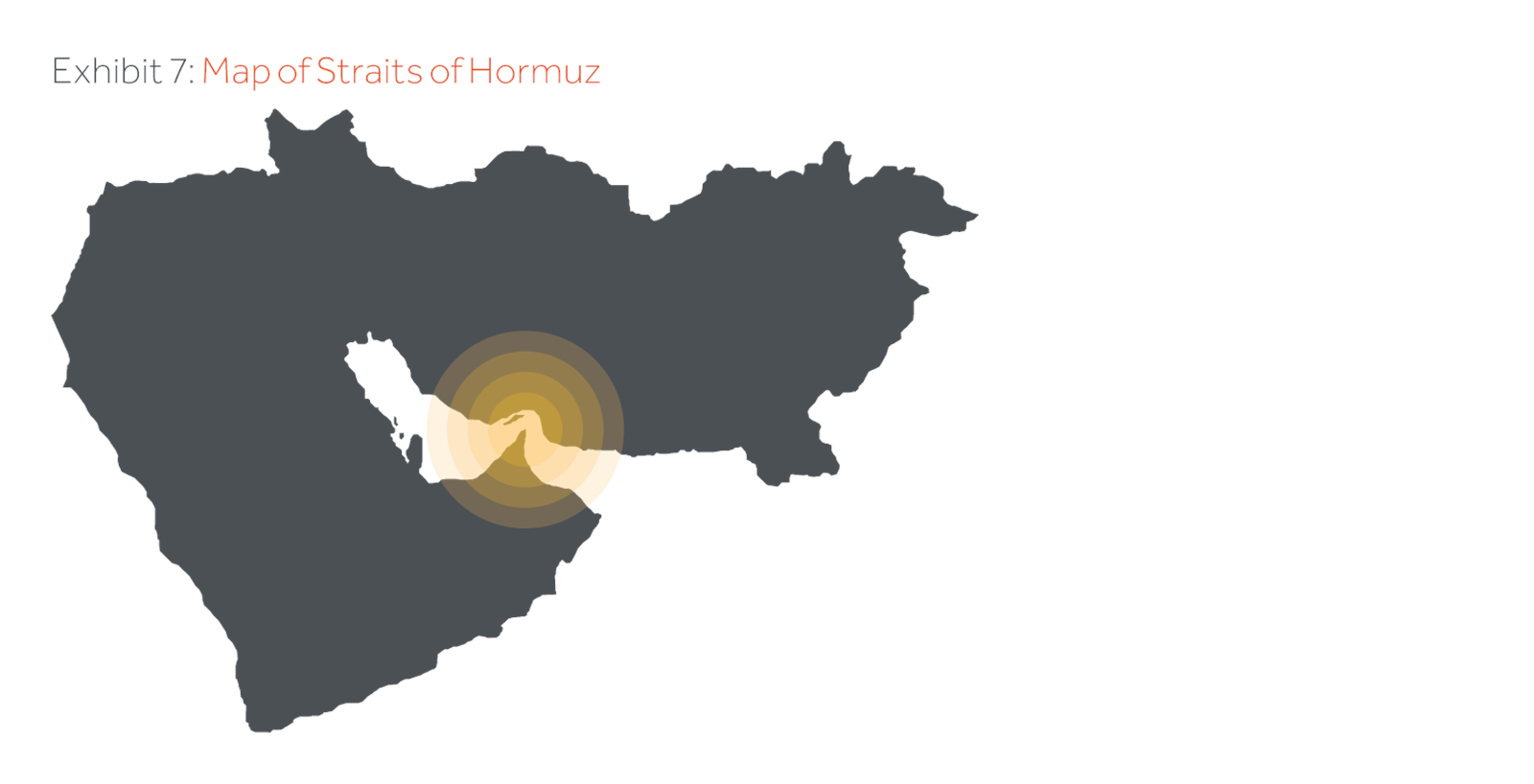

Block the Strait of Hormuz– Either selectively to some countries’ ships, or to all commercial shipping. Whilst this would provoke an international response, it would not lead to the invasion of Iran.This would only be worth doing if Iran’s oil exports were already blocked, otherwise Iran would be blockading itself.

Terrorist attacks– in Western Europe by Hezbollah. These would be deniable but would make the European electorates question why they were getting sucked into a dispute with Iran.

Threats

The US– The US will never accept the Islamic regime in Tehran. To accept Pompeo’s 12 demands would be a surrender of sovereignty which no state could accept. A combination of sanctions, cyber attack, and limited conventional strikes to destroy elements of Iran’s defence forces could bring Iran’s formal economy to a standstill. The US believes a failing Iranian economy could result in civil unrest and threat to the regime.

United pressure from the international community – was what forced Iran to accept the 2015 nuclear deal. If that international consensus were re-established, and became harder line, it would be problematic for Iran.

Iranian policy options

Iran will feel there is no good deal to be done with the US but recognises the status quo is not sustainable. Therefore, something needs to change.

The balancing act– If the big powers remain disunited on their policy Iran has a much better negotiating position. Therefore, Iran must not inadvertently bring them together in a way they did in 2015.

China, France, Germany, Russia and UK (in Iranian trade order) continue to support the JCPOA accord but each has a distinct set of national interests to support. Iran calculates they will not abandon the nuclear deal without a credible alternative.

Pressuring the European countries to make up the economic shortfall of US sanctions by threatening to reduce compliance still further may go too far. They risk one of the E3 triggering the dispute resolution process that could result in a ‘snapback’ of U.N. sanctions. Iran, supported by Russia, is demanding that crude oil is included in the EU mechanism (INSTEX) for avoiding sanctions.

In a similar vein, further action against shipping in the Strait of Hormuz risks pushing the E3 towards the US position.

Tread carefully– with China, urge increased oil trade and bank the Chinese commitment to a big Belt and Road Initiative investment. China is supporting the export of Iranian oil, but their official imports of Iranian oil are at a three-year low, reflecting perhaps China’s concern over the US trade war.

Succeed with Russia– Part of that would be to win the war in Syria. It would mean a stronger block of mutual support. Turkey’s rapprochement with Russia, means there may be a deal to be done there.

Demonstrate regional reach– Iran will continue to build its strengths, in war technologies, in regional alliances, and through support for Shia militias. The US has been unable to stop this; Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen have got stronger over the past 10 years.

More radical options– If faced with unbearable pressure on the economy, Iran has many options for causing disruption in the West, through cyber and/or terrorist attacks, further disrupting the Strait of Hormuz, and as a last resort, a regional conflict with Israel. Iran feel they would survive a regional conflagration, albeit at a heavy price, but the Gulf monarchies would be more vulnerable to revolution from within.

Think long-term– The nuclear programme is seen as essential as a long-term guarantee of Iran’s sovereignty. In the shorter-term, elements of it are a useful bargaining chip, but not to be given up entirely.

In summary, the key question is whether Iran buckles under extreme pressure or lashes out. US policy assumes a rational reaction with concessions made to relieve economic pressure rather than risk internal unrest and regime change. This ignores the nationalist ideology of the revolutionary elite running Iran and their successful deployment of asymmetric offsets which the US finds difficult to counter. Red lines for the US would be targeting of US military personnel or closure of the Straits of Hormuz. Tehran’s line in the sand is US military strikes on Iranian territory. Crossing one or either of these positions would represent an immediate and noticeable escalation of current levels of political risk with far reaching implications beyond the Middle East.

Prof. Nicholas Beadle

Nick is a former private secretary to successive Secretaries of State for Defence and a cross-Whitehall senior adviser on policy for operations. He led the Cabinet Office Afghanistan/Pakistan Strategy and Communications teams from 2008-10 and served in Baghdad in 2004-05 as the coalition’s senior adviser to the Iraqi Ministry of Defence. He has also worked in No10 and the FCO, and on NATO, European Union, and UN policy. His final post before retiring from the Civil Service was in the National Security Secretariat on the Government’s response to the Libya uprising. Nick became a Senior Associate Fellow of the Royal United Services Institute in January 2012. Nick is a founder member of the Risk Officer’s Number, an empirical approach to economic and geopolitical risk.

Clovis Meath Baker CMG OBE

Clovis Meath Baker was seconded to GCHQ as director of intelligence production from 2010-13. Prior to this he filled senior Foreign Office roles dealing with the Middle East, counter-proliferation and Iran, and regularly attended meetings of the National Security Council, the Joint Intelligence Committee, and COBRA. He has served abroad in Afghanistan (the first time during the Russian occupation, the second time immediately after the fall of the Taleban regime), Czechoslovakia (during the Velvet Revolution), Turkey, Pakistan and Iran. He is an Associate Fellow of the Royal United Services Institute. Clovis is a founder of the Risk Officer’s Number.

Timothy Voake

Timothy is the CEO of Voake LLC and was previously a founder of Eddystone Capital, a long/short equity hedge fund based in New York. Prior to this he was a Managing Director at HSBC, heading Asian and Emerging Markets equities in the US. In 2015 he was made a Consultant Fellow of the Royal United Services Institute. Tim is a founder of the Risk Officer’s Number.