And while there are some signs of improvement in those countries which have been able to vaccinate their populations quickly, for many others, particularly in low and middle income regions of the world, the future remains uncertain.

One particular victim of the virus has been the drive for greater gender equality in emerging economies. Our research has looked at how epidemics – not just COVID-19, but earlier examples such as Ebola and Zika – affect different groups in society. What we have found is that these epidemics cause universal increased gender inequality. Many of the issues are even more pronounced in the Emerging Markets.

Epidemics tend to increase existing gender inequalities in two separate ways: by disproportionately affecting women’s health and physical wellbeing, and by exacerbating the economic disadvantage they face.

In terms of the impact on their physical wellbeing, the dislocation to health systems caused by countries switching more resources to the fight against COVID-19 has impacted women in particular through disruption to maternity services and reduced access to sexual and reproductive healthcare. This leads to increased maternal and neo-natal mortality.

In addition, 70% of the healthcare workforce globally are women, which means they are more likely to be suffering from the burnout and mental health concerns that the virus has caused. Meanwhile there has also been a trend towards increased domestic violence, particularly in countries such as Brazil and Colombia. Indeed in some places, particularly in the most economically-insecure areas, research suggests this has risen by 600% over the last year.

Globally we have seen an increase of more than 100 million women living in extreme poverty over the last 12 months. Women are picking up much of the costs which have come through the shutting down of routine life; taking on unpaid additional care work for example thanks to the closure of schools and offices.

This is a particularly acute problem in low and middle income countries due to the high proportion of women who work in the informal economy, which has often been more adversely affected than the formal one. The fact that people who work in the informal economy are less able to access Government social protection only worsens the outcome.

Why is it women who tend to pick up this unpaid work? There are three main factors driving the trend:

- the sectors they work in;

- the entrenched gender norms across many of the growth markets; and

- the gender pay gap.

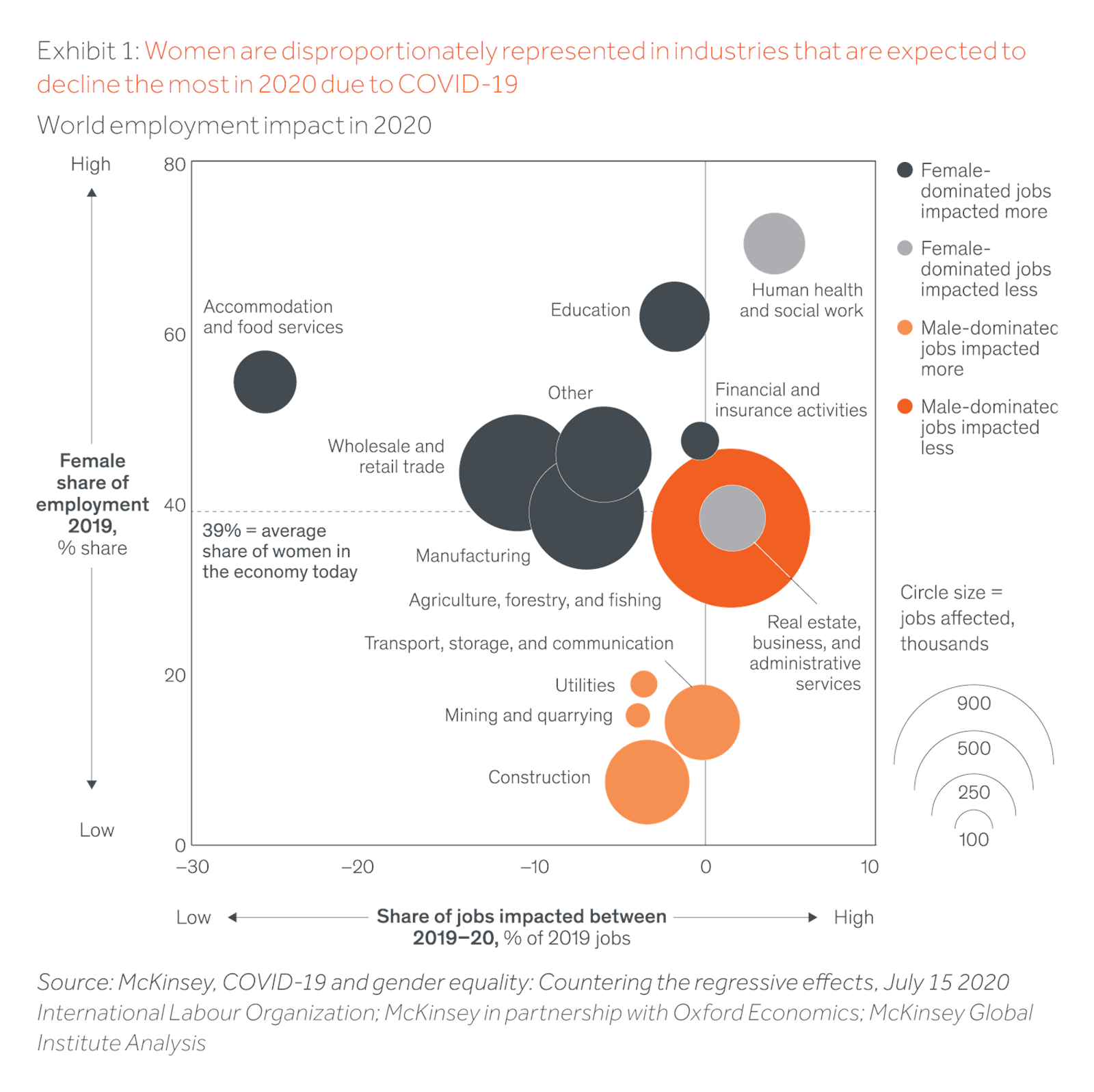

First, women are more likely to work in sectors that have been disproportionately shut down by the virus, such as retail, hospitality and tourism. Since their jobs no longer exist, they are most likely to be the ones taking on the increased domestic burden. Second, entrenched gender norms mean women are more likely to be seen as being the ones responsible for domestic work.

This has been compounded by COVID-19: research shows that existing norms tend to become more conservative during times of crisis. And third, the gender pay gap means it makes more sense economically for women – who in low and middle income economies are much more likely to earn significantly less or work significantly fewer hours – to remove themselves from the jobs market.

In some parts of the world, however, there are factors which mitigate this problem. In countries where people are more likely to live in multi-generational households, such as the Indian sub-continent, there is often a support structure in place to allow more flexible care arrangements which means women can continue to work. However, this obviously raises its own issues because it means potentially exposing more vulnerable people to the virus. The added risk of exposing elderly relatives to COVID-19 means this can be a difficult trade-off for families to make.

It isn’t just working-age women who are being affected disproportionately by COVID-19. The closure of schools due to the virus is also having a particularly negative impact on adolescent girls, most notably in sub-Saharan Africa.

These girls take on much of the household and domestic labour to allow their mothers to go to work. The bigger problem is that too many of them will never go back into education: the history of previous epidemics, such as the Ebola outbreak in west Africa in 2014-2016, suggests dropout rates among teenage girls remain high even after epidemics have been contained.

Indeed looking at past epidemics highlights just how bad their long-term impacts are on getting women into – or back into – the workforce in the growth markets.

A year after the Ebola crisis ended, 67% of men were back in work, compared with only 17% of women. And following the Zika outbreak in Brazil, 95% of women with babies born with Congenital Zika Syndrome are still out of work five years later. The fact that epidemics disproportionately affect women is therefore nothing new.

How can we start to effect change? The good news is that the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has increased awareness of these issues, and people are starting to pay attention. At the global level, the United Nations, the World Health Organization and the G7 for example are having conversations about the subject. It is now on the agenda of international policy makers.

However, we have yet to see the focus on the agenda lead to meaningful change at the national level, which is where most of it needs to take place. Where we have seen Governments in growth markets engage, it tends to be in terms of improving maternity care provision and making efforts to reduce domestic violence.

While these are both extremely important, they do not address the wider problem, which is getting more women into the workforce. This, after all, does not just resolve an issue faced by women: it also supports the wider economy. Governments struggling with stretched finances need data and examples to point out the trade-off between longer term developmental issues and short term fiscal strain.

While some high-income countries are tackling this by increasing child support and improving paid parental leave, not enough is being done in fiscally-stressed low and middle income countries. In particular the focus needs to be on ensuring better childcare and retraining women for the jobs that will exist in the post-COVID-19 world.

Investing in childcare for example, leads to a broader knock-on stimulus throughout the economy, as more women go back to work, and earn money to pay for services which in turn creates more jobs.

What is the lesson for investors from all this? They should constantly ask the companies they invest in how equal their workforce is at all levels throughout the business, what they are doing about gender parity, and what training they offer to women to help them access their jobs.

It is about fostering culture change in many of these places; it is about making opportunities available to women at the same rate as they are available to men.

Investors need to look beyond the financial returns and look at the impact of their investments on society. Investors have a responsibility to support these changes, to help overcome the inequalities that the virus has so clearly exposed and exacerbated throughout the world.