After years in which the public debate about energy policy focused mostly on decarbonisation, the crisis in Ukraine has forced stakeholders worldwide to revisit the energy trilemma. Although governments in the short-term are putting considerations to the fore to keep the lights on, energy security has taken a more prominent role in country’s long-term plans as the world observes European economic disruption and energy hardship as Russia cuts off gas supply. While Latin America may be far from the war, some countries have previously gone through energy security crises of their own, thanks to issues as varied as unreliable neighbours and unpredictable weather. The experiences of Chile and Peru – global pioneers when it comes to liberalising their power sectors – offer some important pointers about the way ahead for other parts of the world.

Both countries have successfully built resilient power systems, in the case of Peru, as well as high penetration levels of carbon-free generation (Exhibit 1). This is in sharp contrast to much of Europe, which is still overdependent on Russian gas. Indeed, South America was an early mover in liberalising its power sector.

“The experiences of Chile and Peru – global pioneers when it comes to liberalising their power sectors – offer some important pointers about the way ahead for other parts of the world.”

Exhibit 1: Carbon Intensity of Electricity, 2000 to 2021

Carbon intensity measures the amount of greenhouse gases emitted per unit of electricity produced. Here it is measured in grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour of electricity.

Chile was the first to pursue comprehensive market reforms beginning in 1978, adopting elements that traced their ideological foundations to Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek at the University of Chicago. By the 1990s, the liberalised power sector model was common across Latin America, driven by the poor performance of state-owned enterprises and the burden they placed on the region’s fiscal position.

Chile’s transition to becoming self-dependent yet clean stemmed from efforts to diversify sources of power generation and primary energy supply which were driven by forces outside its control. In the past, Chile sourced most of its natural gas from Argentina. So cheap was the supply from across the border thought to be that the country began to increasingly rely on it for power generation over its hydro power plants, which before the gas from Argentina arrived covered 80% of the country’s energy needs.

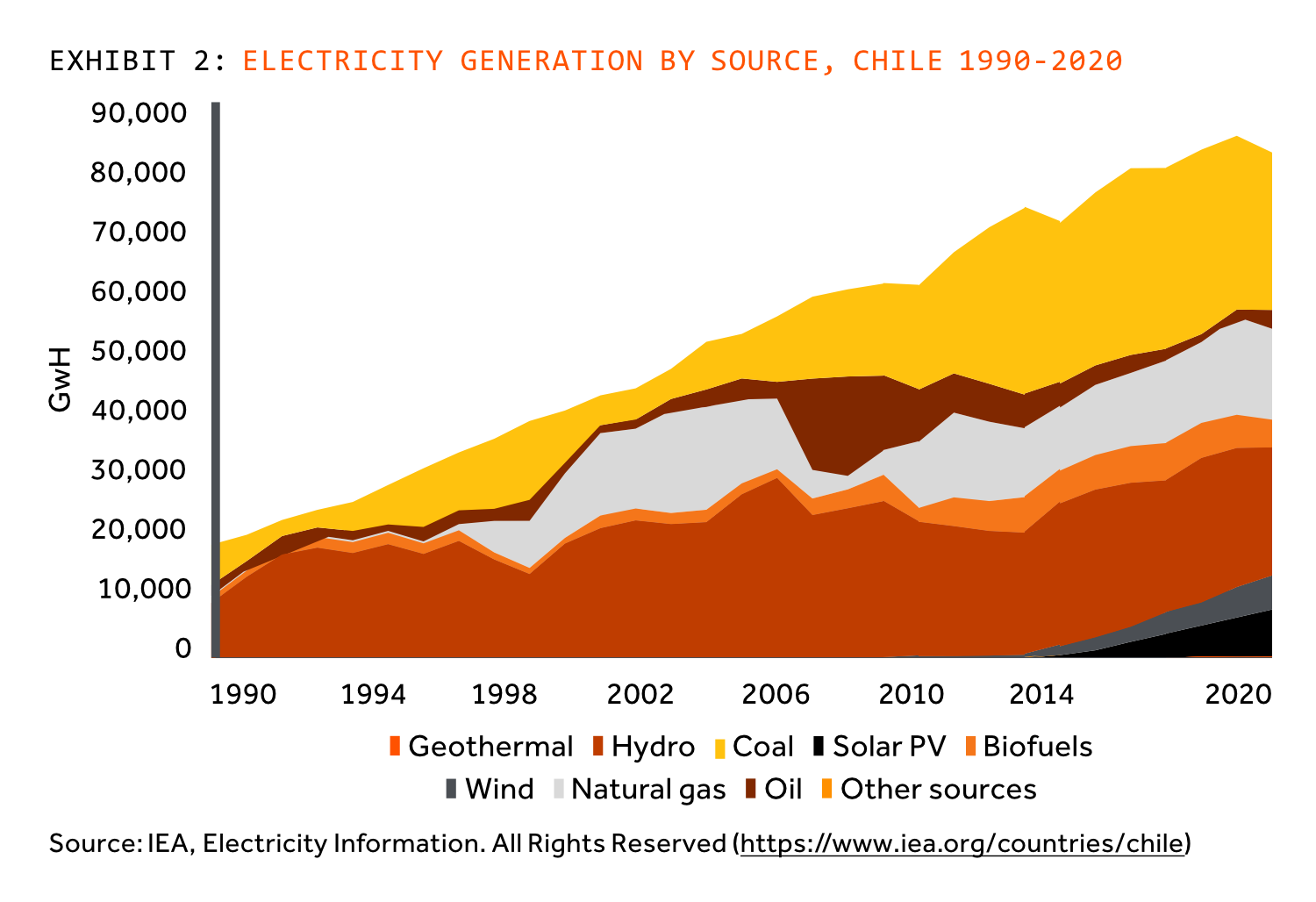

However, Argentina cut off supplies to Chile in 2004 to prioritise its own domestic energy needs, forcing Chile to act quickly. It built two regasification terminals to supply the country, reducing its cross-border dependency. Although the country was forced to turn to coal to fill the gap caused by the withdrawal of supply from Argentina (Exhibit 2), it also successfully introduced a series of incentives and regulations to foster more sustainable energy production. As part of its decarbonisation goals, generation companies signed agreements with the government to retire over 1,000MW of coal-fired generation within the next 5 years and close the remaining plants by 2040. In fact, this timeline has been accelerated, and it is expected that half of the coal generation fleet will be retired by 2025.

On the back of energy requirements from distribution companies, the country tendered high price Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for renewables. Thanks to its competitive bidding framework, it was able to boost competition in supply auctions and improve system operations, while regulating capacity to ensure adequate generation. As a result of these efforts, Chile has seen a meaningful increase in renewables penetration, while achieving decreasing costs. The first vintage of renewables auctions in 2013 saw PPAs priced in average at $129/MWh. In 2021, prices in the renewables auction averaged as low as $24/MWh, before raising to $37/MWh in the latest round in 2022 on the back of inflationary pressures across the supply chain. In any case, as lower priced power increases its share of the generation cost to distribution companies, end users expect to see declines in their electricity bills going forward.

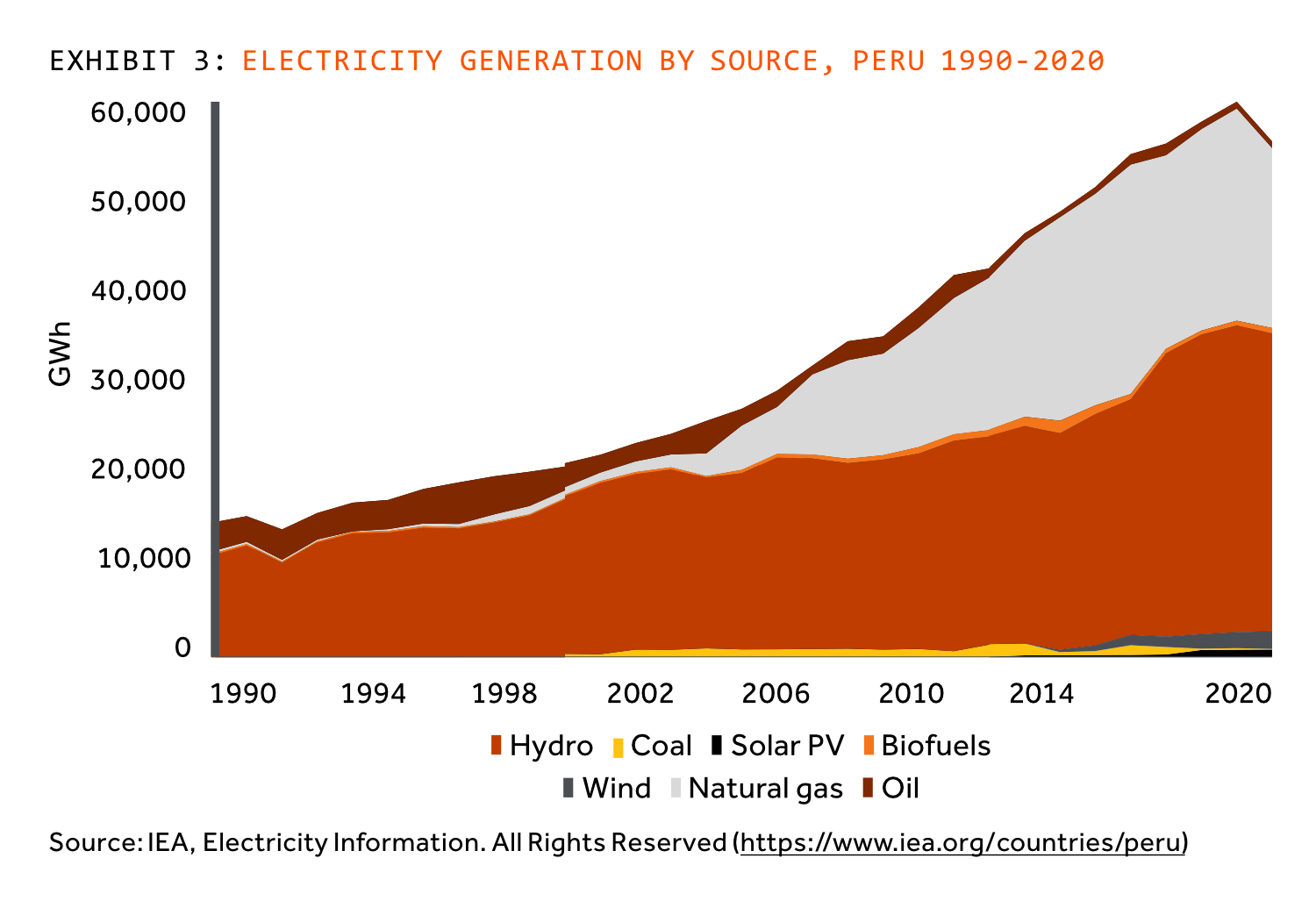

Peru faced different issues. Its supply constraints did not come from geopolitical problems, but from changing climate patterns. Until 2004, hydroelectricity generation met 80% of the country’s requirements with the balance mostly from fuel oil and diesel. However, a series of droughts exposed the system’s weakness and galvanized the country to invest in Camisea, a natural gas project which created the necessary infrastructure to supply energy in a secure way. Hand in hand with that went the buildout of natural gas fired generation plants. Today, the generation matrix is split 50/50 between hydro generation and natural gas fired generation, with a nascent renewables’ environment (Exhibits 2 and 3). This combination of locally sourced natural gas and hydro + renewables results in energy wholesale prices that hover in the $20-30/MWh area for 2022 – some of the lowest in the world.

The lesson for others when it comes to Chile and Peru is of the dangers that can arise when you are overdependent on a single, or dominant, source of energy. To combat the problems they faced, both nations refocused domestic political priorities on energy security, diversifying energy production and ensuring security of supply, demonstrating the important role governments can play in driving change. Competitive bidding was vital for both markets, establishing public auctions for contracting new generation capacity and therefore responsibly transitioning each of the countries’ matrices to a secure and sustainable mix. The region also accepted natural gas as a transition fuel, a viable, affordable, and reliable option to accelerate the decarbonisation process. Meanwhile the competition engendered by the processes helped keep costs relatively low.

“On virtually every type of reform measure, Latin America and the Caribbean has been a pioneer.”

According to a 2019 World Bank report entitled ‘Rethinking Power Sector Reform in the Developing World’Peru and Chile faced vastly different problems, and have vastly different energy generation mixes. Yet both in their own way found a balance between energy supply, access, and the transition. Countries in Europe could well learn lessons from their experiences.

Alberto Estefan and Maria Cox work in Actis’ Energy Infrastructure team in Mexico City