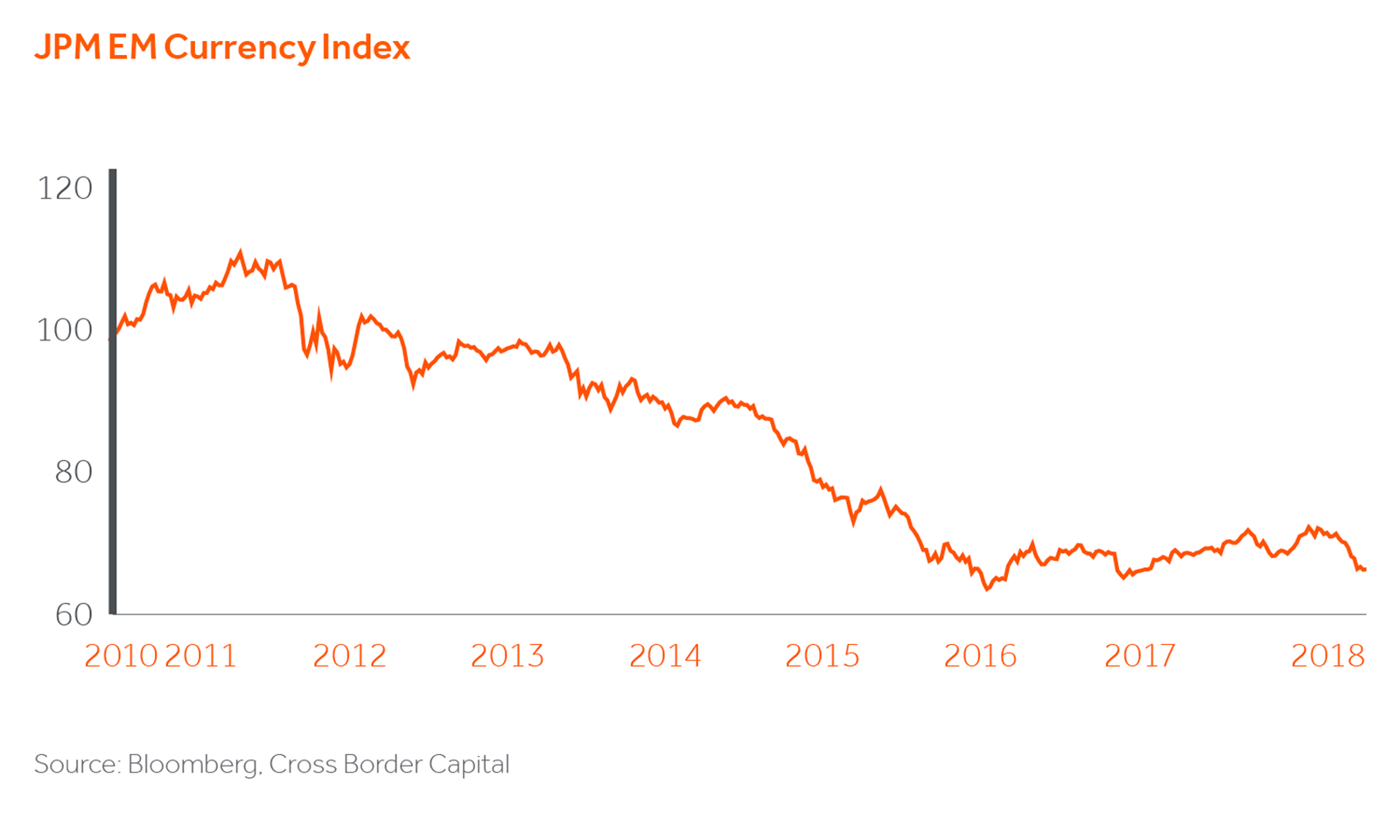

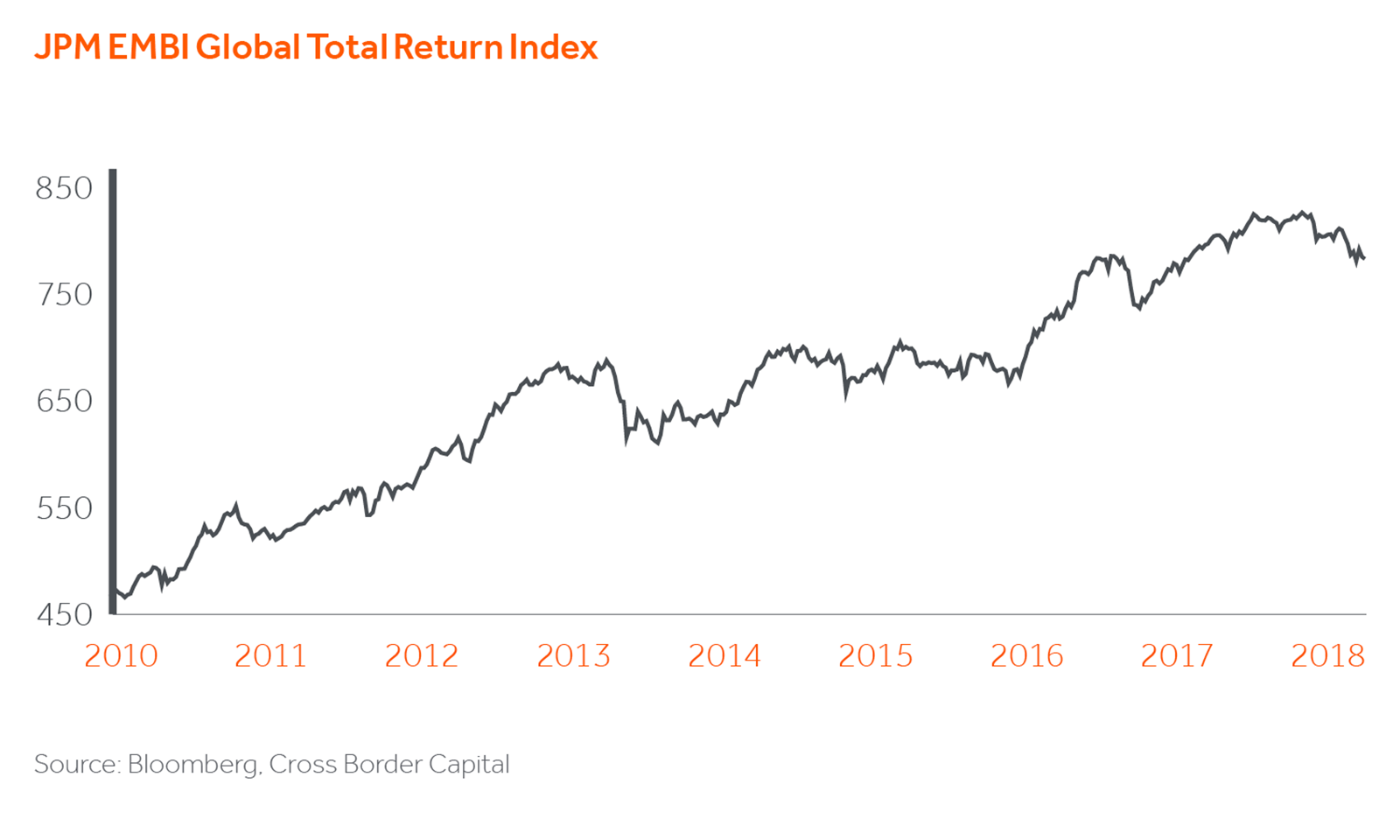

By now Emerging Market investors know that weakening currencies spell danger for returns. Bouts of extreme global volatility such as those which swept through the asset class in 1997, 2001 and 2008 had enormous impact on economies, businesses and capital markets. More regional crises such as that set off by the commodity slump in 2014-16 have similar effects on specific areas. And self-imposed wounds brought on by domestic policy mishap or political events (think Turkey and Argentina in recent months) have very specific country impacts.

The reasons vary by country but have one central theme, the vulnerability of countries which rely on portfolio flows to plug financing gaps left by shallow domestic financial systems. Whilst this has been the case for decades, the bulls argue that distinct regional and country differences exist which require closer examination.

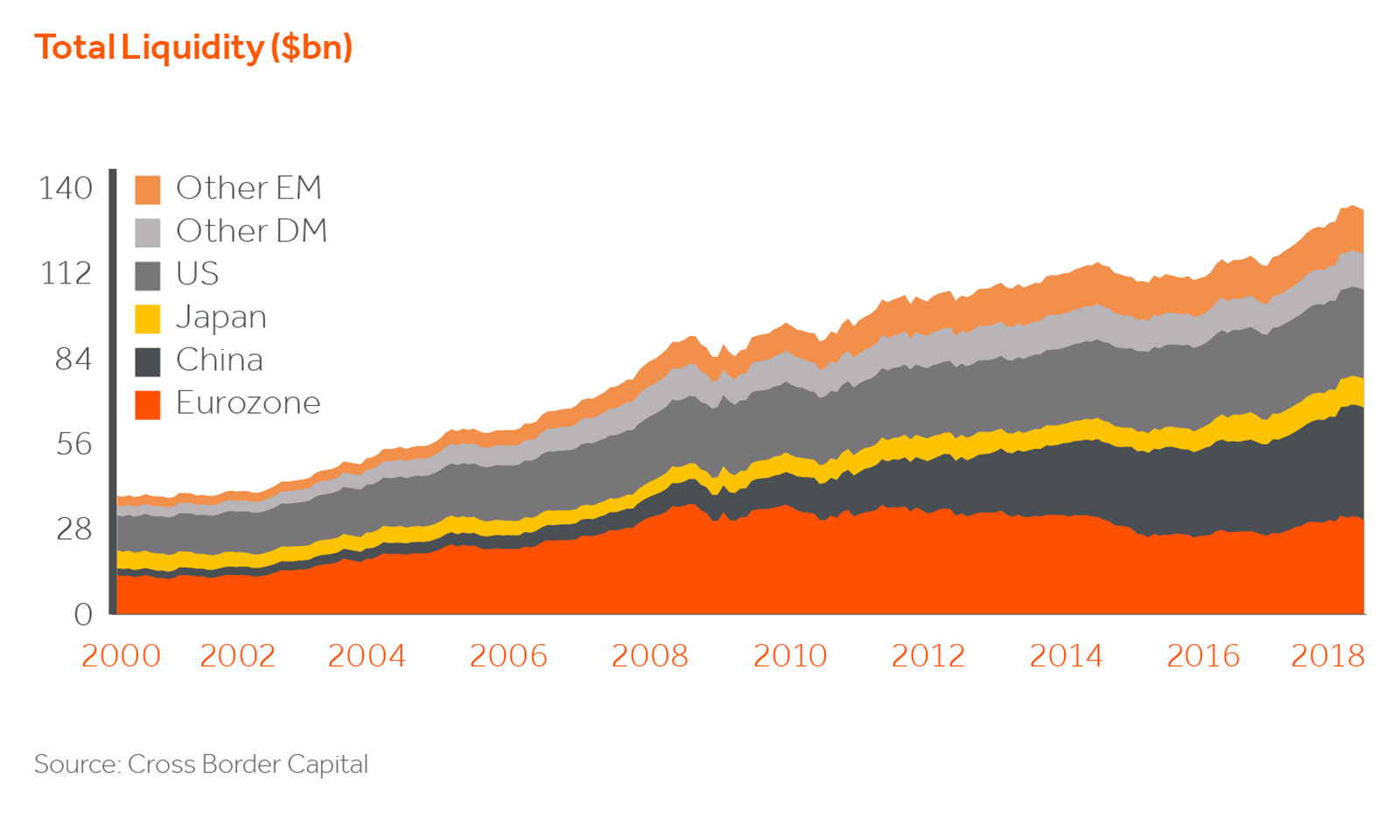

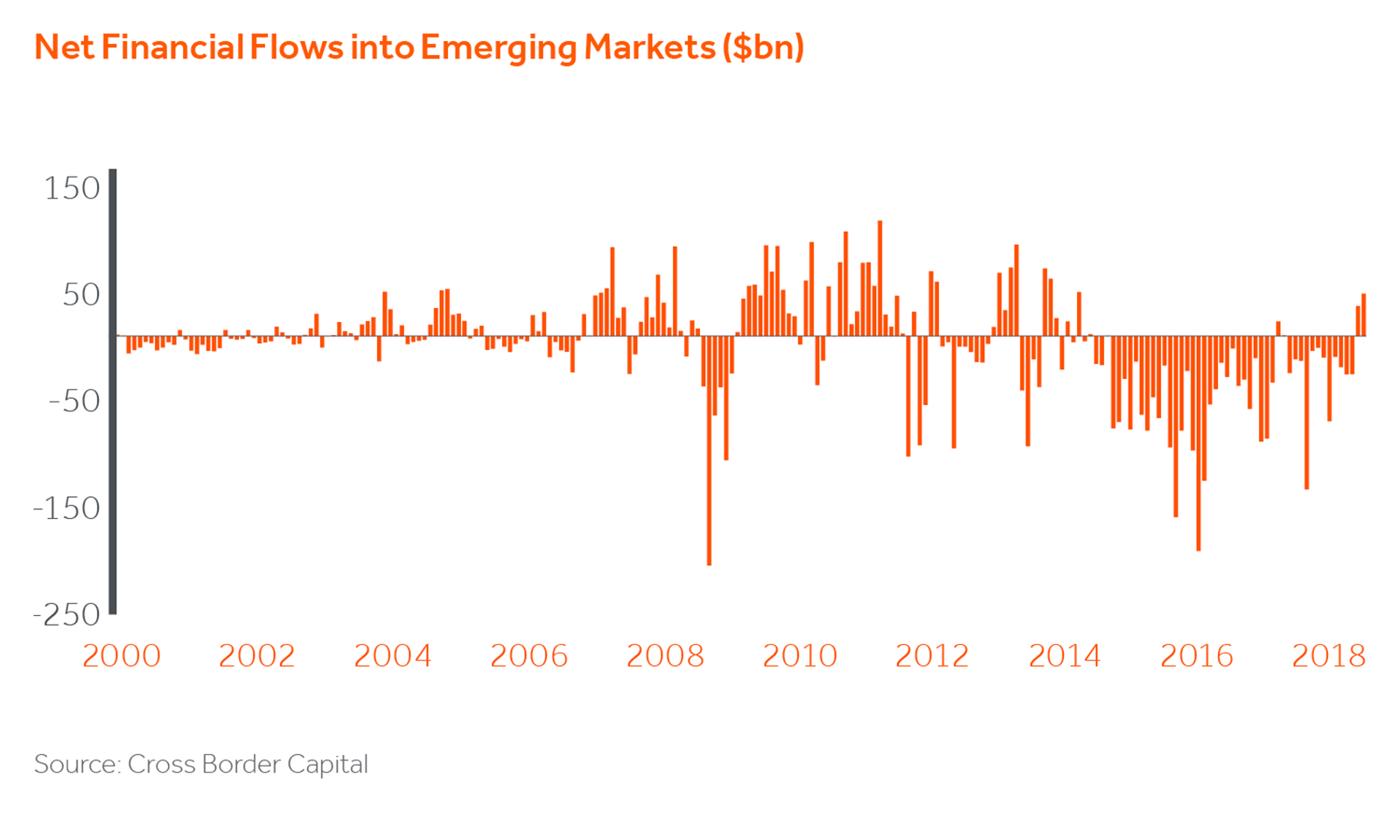

Clearly global financing conditions have tightened materially in recent months as seen in rising US interest rates and declining central bank balance sheets. The tidal wave of liquidity which allowed many third and fourth tier borrowers easy access to global capital flows has begun to abate both because the QE gusher is abating and because increases in global economic activity are pulling money out of financial assets and into capital investment and working capital needs.

The immutable rule of a tide going out-that you see who has been swimming without trunks on, also applies. In recent months there have been serious sell downs in the Turkish lira and Argentine peso whilst on a lesser scale South Africa, India and Brazil have seen their currencies start the familiar slip which has presaged difficulties in the past.

The bonds of recent frontier issuers such as Tajikistan and Iraq stand well below their issue prices. There have been substantial flows out of EM assets-US$12.3bn in May alone according to the Institute of International Finance. Is this the beginning of another difficult time for EM investors?

We suspect that these are passing clouds rather than full scale crisis. Why?

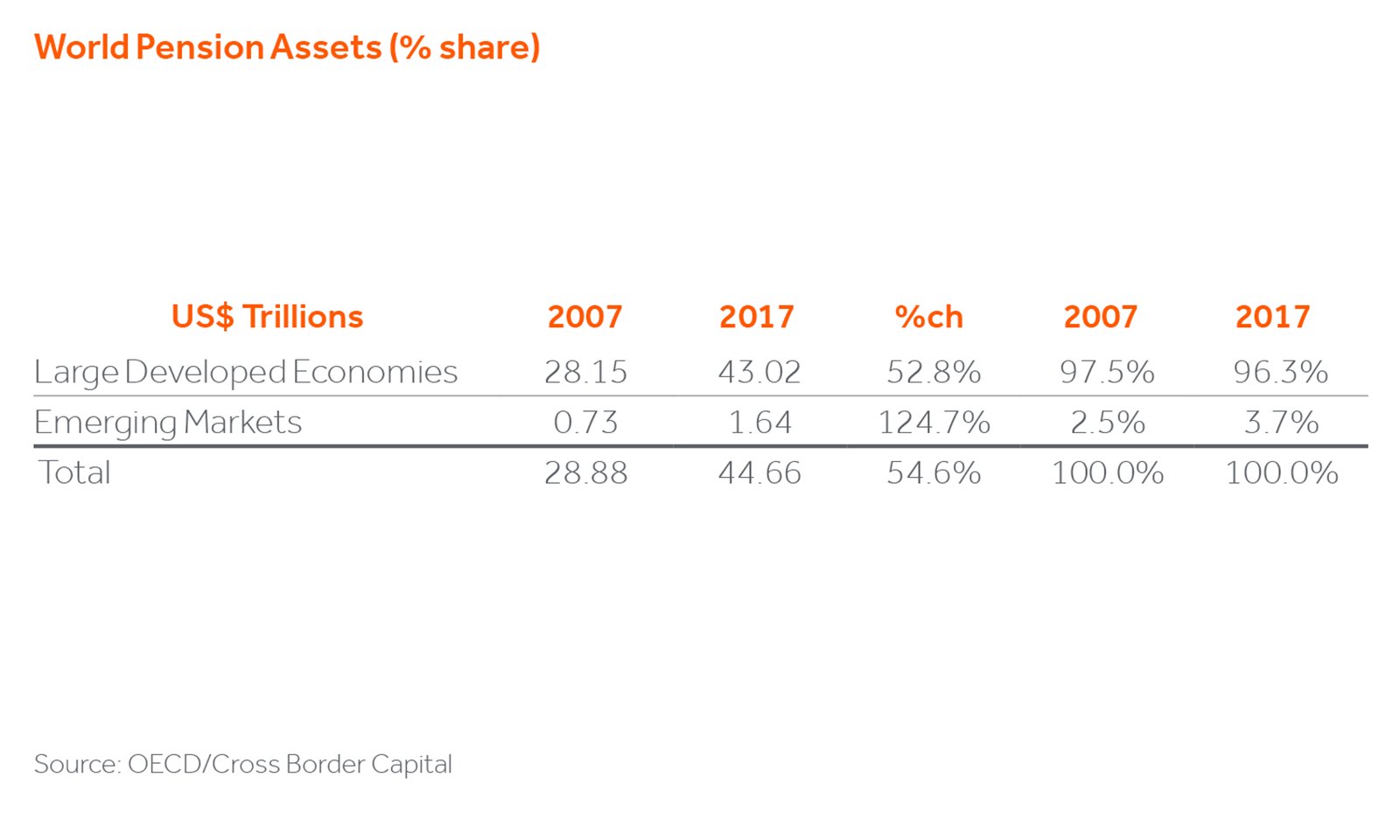

Firstly, by contrast with the 3 big global crises (1997/2001/2008) the domestic savings bases of EM countries are far bigger.

Not least the balance sheets of EM central banks are in general very healthy. The largest single EM-China, whilst struggling with domestic debt issues arising from mis-allocation of capital owes these monies to itself and not to foreign creditors.

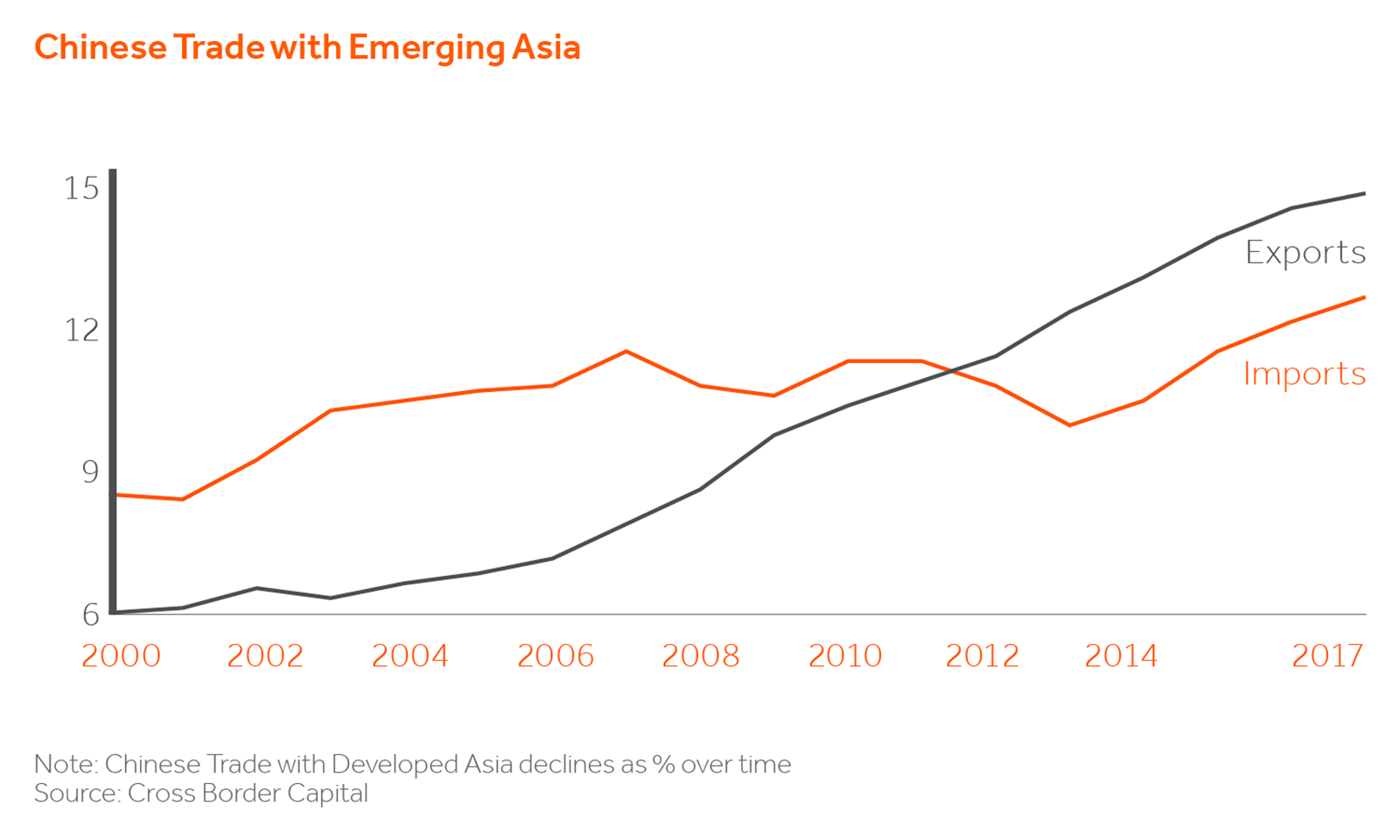

Secondly, the sheer size of the Chinese economy means that it can form a source of demand for client nations. The rising share of trade for Asian countries with China means that policy makers from Tokyo to Colombo are increasingly more interested in targeting their currencies against the RMB as opposed to the dollar. We expect this to be a multi decadienal process.

Thirdly, strong Central Bank balance sheets mean that these banks are under less pressure to raise rates as capital flows out unless there are significant spikes in domestic inflation. This is obviously more the case for the richer EM countries where domestic savings can absorb capital outflows. In Asia for instance last year nearly 75% of US$ finance raised came from domestic savers and currency volatility in many LatAm countries with large savings bases (think Mexico/Chile, Colombia, Peru) remains historically low.

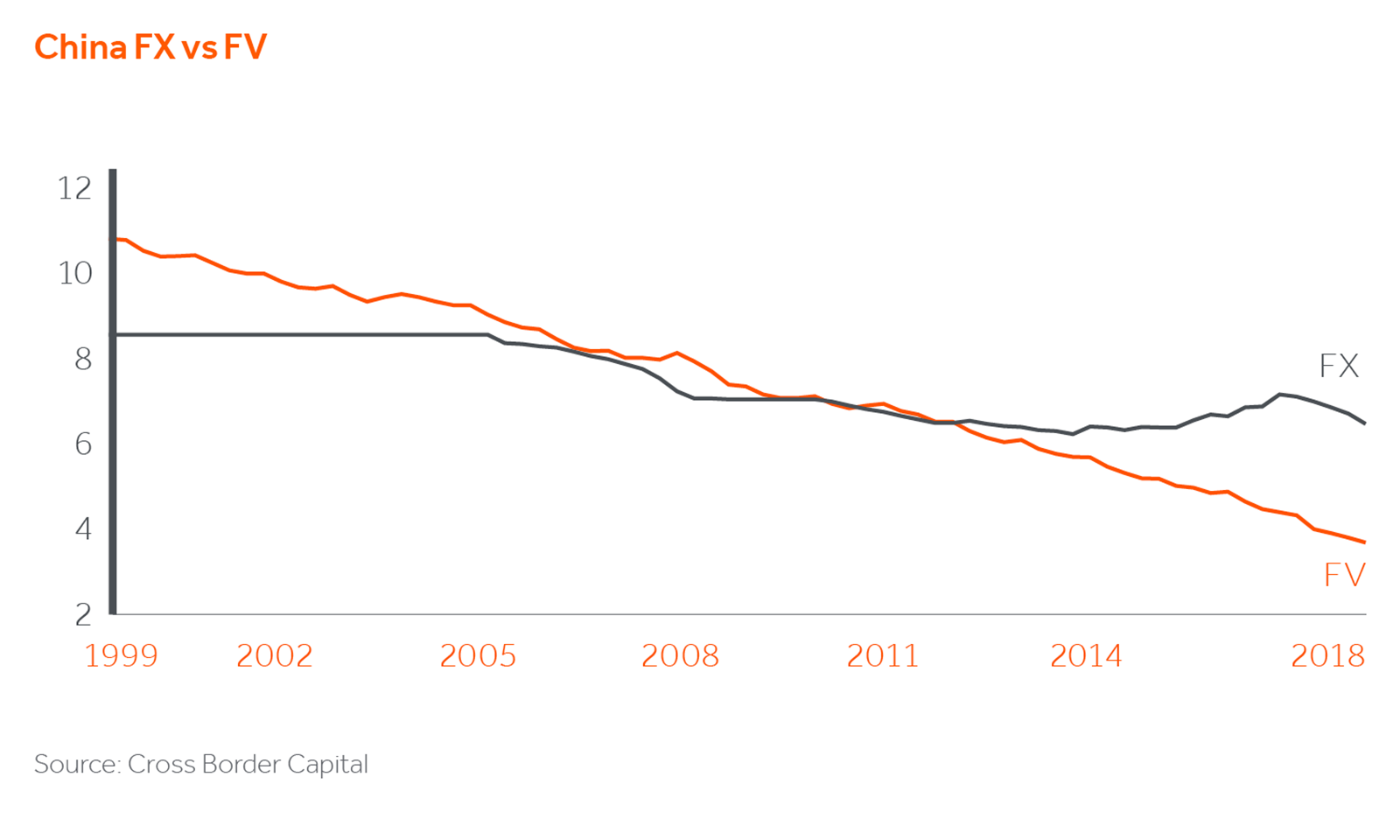

At Actis we fully acknowledge the importance of exchange rates and run our own models of currency values. At present despite some volatility we cannot see any major currencies which are noticeably over valued whilst the RMB appears undervalued which in turn is helping the financing conditions for many Asian countries.

Our portfolio companies in general are not reporting material changes in business conditions although many are rightly watching the development of trade diplomacy with considerable concern. Political developments over the summer include key elections in Mexico and Brazil (covered elsewhere in this edition) and continuing pressures for reform in Africa (covered in our sister publication African Voices). Our base conclusion and long term investment conviction is that EM fundamentals, whilst vulnerable to externalities (in particular trade diplomacy) are not in danger of collapsing even though individual countries face specific challenges in less propitious funding markets than those of the last 18 months.