Shami Nissan: Why are we at such a crucial junction with critical minerals and the transition to Net Zero?

Rohitesh Dhawan: The Northern Hemisphere has faced a relentless summer of extremes. July 2023 was the hottest month on record globally, with wildfires ravaging Greece, Syria, Canada, and Spain, causing a tragic loss of life alongside environmental devastation. The harsh reality of climate change is hitting populations worldwide, and scientists believe it is only a taste of what is to come. As temperatures soared, oil demand reached an all-time high, according to the International Energy Agency. While ambitious net zero targets have been set and investment in renewable energy systems is rising, the structural transformation of global energy systems to wean ourselves off of fossil fuel is at risk of remaining a distant dream.

What these events have brought into sharp focus is that the world is significantly off-track to meet the global goals set out in the Paris Agreement. There is increasing concern around the lack of raw materials required to create the clean energy the world so desperately needs. Supply of some metals and minerals will need to increase up to 20 times in the next 30 years, and people are concerned that this will lead to a mad rush for critical minerals which will only exacerbate existing social and environmental challenges. I don’t think anyone would deny that we are at one of the most critical junctures in the history of the mining industry. Society rightly expects that miners need to operate in a way that care for people and the planet, which is true for many companies especially those who have self-selected to be part of The International Council on Mining and Minerals (ICMM), but not of all.

Shami Nissan: How would you describe the risks we face as a result of this challenge?

Rohitesh Dhawan: When I think about the challenges, I think about the three S’ – ‘supply’, ‘strategic’ and ‘sustainability’. Taking ‘supply’ first. If we look at the supply vs demand equation there is a clear imbalance. We’ll need around 3 billion tons of metal to reach net zero by 2050 as essential building blocks of wind turbines, solar panels, and electric vehicles. This demand comes on top of their use in buildings and infrastructure that is also growing as the global population grows and becomes richer. There’s no shortage of minerals needed in the ground, but we are currently not producing them quickly enough, especially for commodities like copper, lithium, cobalt and nickel. Without doubt, we need to maximise supply from metals already in circulation and implement material substitution wherever possible, but even with maximum recycling, mining will need to grow materially.

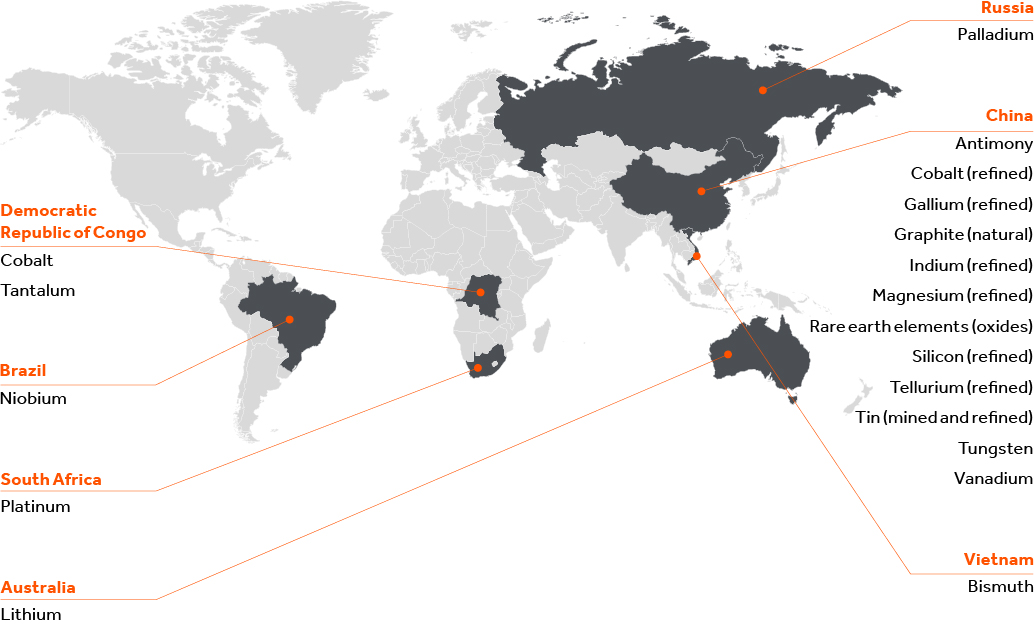

By ‘strategic’ I am talking about where these metals come from and the related geopolitics. Critical minerals are now a top-level national security and geopolitical issue, and that could shape both demand and supply for these commodities. We’re likely to see countries work unilaterally, bilaterally, and multilaterally to try and secure supplies, especially with and from other like-minded countries – the Minerals Security Partnership is just one example of this. This could exacerbate existing geopolitical tensions but could also lead to some unlikely alliances which would be positive.

Critical minerals are now a top-level national security and geopolitical issue, and that could shape both demand and supply for these commodities.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, ‘sustainability’. In short, the concern here is that the ‘cure’ isn’t worse than the ‘disease’. In other words, that in our rush to grow mineral supply to power the decarbonization technologies of the future we don’t end up with huge collateral damage to people and the planet. When done responsibly, mining is in fact one of the most powerful forces to meet all the Sustainable Development Goals but when done irresponsibly, it can cause real harm. We have so many good examples of responsible mining and the key is to make those the norm, and to continue to raise the bar.

Shami Nissan: The mining industry is poised for a large spike in demand, but is it ready to meet regulatory and societal expectations on sustainability, including how extraction, processing, refining and other processes are performed?

Rohitesh Dhawan: I have personally seen a very clear and genuine commitment, particularly on the part of ICMM members, to take steps to address societal and regulatory concerns. However, we as a mining industry must put our hands up and acknowledge that performance has not always met expectations. We don’t have the trust and confidence of society at large. It’s not hard to pinpoint why – the collapse of the tailings dam at Brumadinho, Brazil the events at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia and well publicised incidents of corruption have all contributed to this.

What is less widely reported are the examples of responsible extraction and good practice which are taking place across the industry. One great example is the work Anglo American is doing at their Quellaveco project in Peru. Working with communities and the regional government, they have gone above and beyond the legal and regulatory requirements for a new mine. This includes agreeing 26 specific commitments relating to water management, environment, and social investment. They have also provided 29,000 local jobs through the construction of the project and an expected 2500 now the mine is in production. It is these kinds of positive examples that we not just need to talk about but ensure that we learn from and encourage all miners globally to adopt.

Supply of some metals and minerals will need to increase up to 20 times in the next 30 years.

Shami Nissan: What should investors (like Actis) do/demand?

Rohitesh Dhawan: I am going to use two examples to illustrate what investors can and should be doing. Firstly, on tailings. Tailings are a byproduct of mining, consisting of ground rock, organic matter and effluents. If not managed properly, tailings can have adverse impacts on the environment and human health and safety, with pollution from effluent and dust emissions being potentially toxic to humans, animals or plants. Investors played a critical role in supporting the industry’s journey towards more responsible tailings management. This was through the Principles for Responsible Investments’ role alongside UNEP and ICMM in developing the Global Industry Standard on Tailings management. There is an unwavering commitment from ICMM members to implement the standard, but we need to also see this from the wider industry. Here actions of investors such as the Church of England have been critical. They have said publicly they will vote against boards who are not implementing the standard. Investors should look to take the same approach for other key challenges – help to identify good practice, then apply pressure on companies to implement.

The second example looks at what investors should be doing. I believe that in some cases, the rhetoric of investors does not match action. A good example of this is the issue of nature and biodiversity. I have heard many investors speak about this issue publicly, but I have heard that these issues are not being brought up in direct engagements with companies. It is not simply a case of challenging companies publicly; investors must be willing to offer their support to companies to drive the change needed.

EXHIBIT 1: TOP PRODUCERS GLOBALLY OF THE 18 CRITICAL MINERALS

Note: Country with the highest production of each critical mineral; refers to mined production, unless otherwise stated. 5-year average production 2016-2020.

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, Resilience for the Future: The UK’s Critical Minerals Strategy (March 2023).

Figure contains data from the UK Critical Intelligence Minerals Centre, British Geological Survey © UKRI 2022.

Shami Nissan: Nature & Biodiversity is a huge growing topic. Nature-positive mining – will it ever be possible?

Rohitesh Dhawan: When considering this it is important to note that ‘nature positive’ refers to the state of nature and is not a description of an activity. So, we should avoid describing companies or sectors as being nature positive or not – at least until the metrics and standards for nature are sufficiently well developed. The mining industry therefore has an opportunity to create a nature positive future, by minimizing our negative impacts on nature and contributing through conservation and preservation activities.

The most critical task, which ICMM members have committed to doing, is to apply the ‘mitigation hierarchy’ with an ambition of no net loss of biodiversity. This means taking steps to first avoid negative impacts on nature as far as possible, minimizing those that can’t be avoided, remediating any residual impacts, and only using offsets as a last resort. ICMM members have also committed to not exploring or developing new mines in World Heritage Sites and to respect legally designated protected areas – something that I think should be a baseline expectation of all mining.

Mining companies also have an opportunity to contribute to nature positive outcomes beyond their immediate operations. Some members are leading actors when it comes to conservation, restoration, and preservation of biodiversity and nature. For example, Vale helps protect nearly 1 million hectares of land across the world, including 800,000 hectares in the Amazon. Or that Anglo American is using eDNA to manage, measure and share 30,000 data points on water quality and biodiversity to achieve a net positive impact in North Yorkshire.

Shami Nissan: Circular economy and recycling – will we get to a point where we don’t need to mine at all because all that we need is in circulation already, or is that fantasy land? Will we have to resort to deep sea mining?

Rohitesh Dhawan: The reuse and recycling of metals already in circulation is critical to help the world meet demand. However, this alone will not be enough to service the expected rise in demand for key commodities. We will still need to see a significant growth in primary production. For example, 2/3rds of the copper mined since the 1900s is still in circulation. Copper production, however, is expected to double between now and 2050 to meet demand. This is the same across several other critical minerals. We will still need to responsibly increase the supply of new metal, but we must work to supplement this with the reuse, remanufacture or recycling of existing materials. It is especially important this is done through mechanisms that value the durability of materials. Specifically on deep sea mining, it can be a source of critical minerals, but the risk of harm is significant and not yet fully understood. While mining on land is not without risks, we understand and can control associated risks better than we currently can in the deep seas and no ICMM member currently engages in Deep Sea Mining.

Shami Nissan: What makes you optimistic/hopeful?

Rohitesh Dhawan: There are so many examples of mining in harmony with nature and people, and I’m really hopeful that we can make those the norm. Even when we start from a bad place, we can still end up where we need. For instance, consider Ite – Peru’s largest wetland. It is a pristine and thriving 12km long wetland where I saw crystal clear water, flamingos, and other incredible birdlife – it’s a completely idyllic natural ecosystem. 20 years ago however, it was the opposite. Mine waste (tailings) had been deposited there for several years, and it was a barren and lifeless wasteland. Southern Copper, through their restoration project, has helped turn a landscape which was degraded into something that is healthy and thriving. It gives me hope that even in the most challenging circumstances the industry, communities, and regional authorities can work together to create a more positive future.