Central and Eastern Europe is often seen as a major destination for investment activity thanks to its potential for economic growth and legacy underinvestment. But it has several unique features which can mean challenges for outside investors – particularly those in the infrastructure sector – who wish to deploy capital and take part in its transformation. Actis’ Neil Brown spoke to Lucyna Stanczak-Wuczynska, one of the region’s most respected bankers with close to 30 years’ experience in banking and private equity and a Strategic Advisor at Actis, to discuss the opportunities that may be available.

At the time of publishing, Central and Eastern Europe has been significantly affected by recent events unfolding in Ukraine. Short term, the crisis has both humanitarian and economic impacts; the humanitarian crisis is awful and real, and our hearts extend to those affected. Economically, in the short term we see raised risk premia for the region. This is not surprising – these types of crises often result in an immediate spike in volatility. The timeframe for this volatility is unclear at this point, though it is likely to persist for some time. Long term we believe the investment themes that we back – including the energy transition and the digitalisation of Central and Eastern Europe economies – will persist, and in fact may be accelerated by the tragic events that are unfolding. We recorded this interview before the events in Ukraine, but have decided to publish this piece given the global thematics are long term investment theses.

Neil Brown: Are there infrastructure sectors in Central and Eastern Europe that are more attractive than others? What are the region’s main infrastructure needs?

Lucyna Stanczak-Wuczynska: The whole region has witnessed remarkable achievements in the last few decades: doubling its GDP per capita, attracting foreign investors and emerging more resilient from the Global Financial Crisis.

In respect to infrastructure, despite substantial investments, there still remains a great deal of inefficient heavy industry in the region, including ageing or even obsolete energy assets, with a very significant continuing dependence on fossil fuels (especially in Poland, Czech Republic, Serbia and Moldova). This means low quality air for the population. There is less dense transport infrastructure than in the Western European Union but good – if still uneven – access to broadband. More structural reforms are needed, particularly when it comes to the efficiency and quality of governance at state-owned enterprises – around 70% of infrastructure assets are still state-owned.

I think the most important infrastructure need is better connectivity across borders – that’s both within the region and across the rest of Europe. That includes better rail, road and digital infrastructure. The second area of need is the energy transition towards low carbon and energy efficient infrastructure – as the share of renewable energy is still quite low, generally between 10% and 20% in the majority of the countries (especially in South East Europe and Western Balkans) and the path towards a Net Zero economy will require substantial efforts. And the third area is digital transformation, whether it is 5G, the ‘Internet of Things’, sustainable data centres, or access to flexible networks. Overall, I think the region is very open to transformation and has great prospects.

Neil: What should be the role of the public and private sectors? Should governments be providing regulatory and legal certainty, or are there other roles they can play?

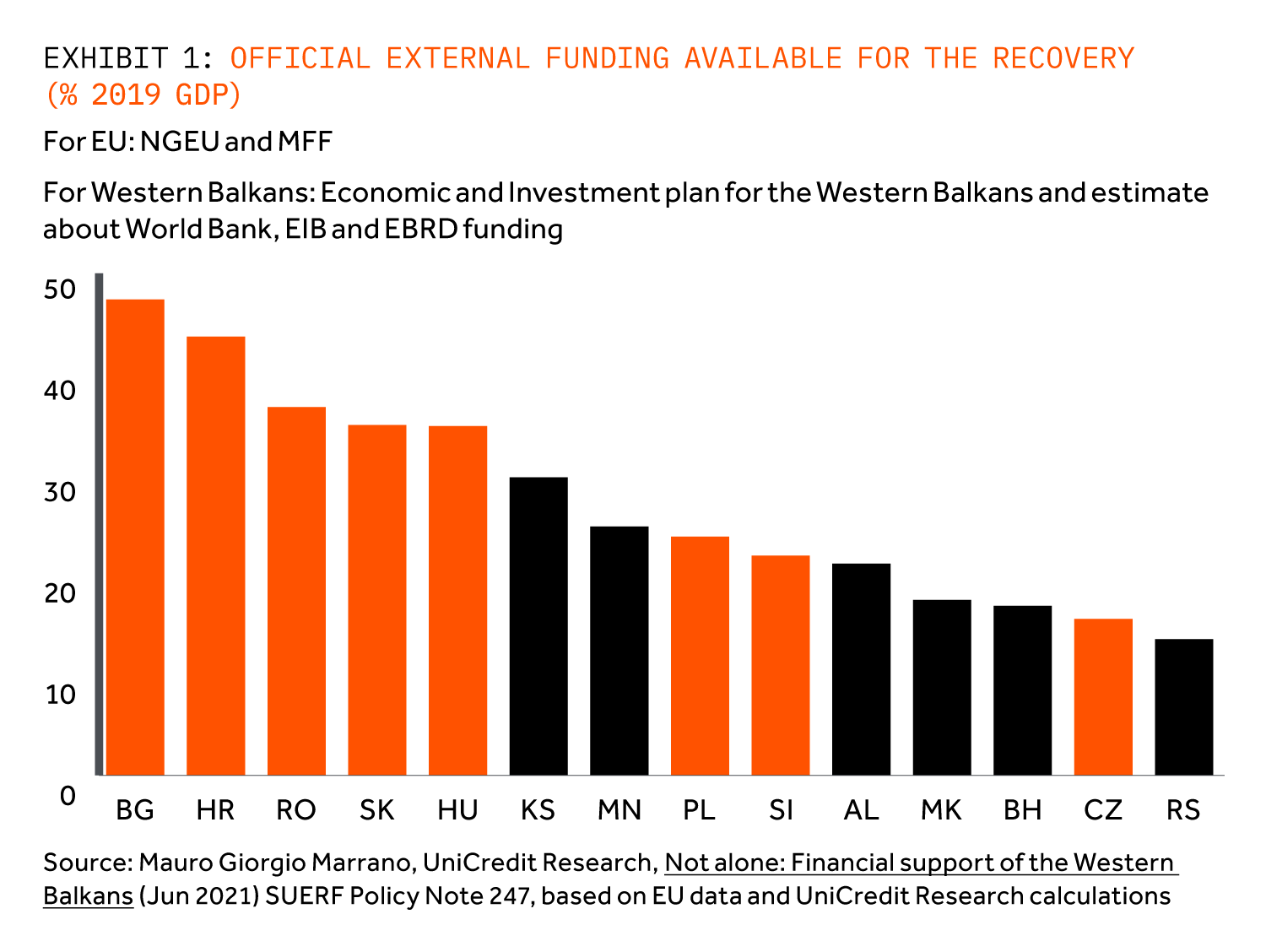

Lucyna: The sheer scale of infrastructure investment that is needed won’t be possible without the private sector. If we are to meet the requirements of the Paris Agreement, even with vast support from various European investment funds (in particular Next Generation EU and EU Multiannual Financial Framework funds, that may reach even up to 12% of GDP of some of the Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe countries, such as Croatia or Bulgaria), (See Exhibit 1) there will still be a significant need for private sector involvement. But how this cooperation between private and public should work is not always simple. Projects in the region can face challenges in terms of lengthy procurement, structuring, design and preparation. There are frequent cost overruns and delays. The major challenge is to deliver robust and bankable projects, with effective risk sharing between private and public participants.

Encouragingly there are now new systems of support for the renewable sector, greater transparency, stable legal frameworks and a favourable climate to do business. There is also greater support coming from international and local development finance institutions. There are some landmark public-private partnership projects in the region, in particular in the motorways sector.

Neil: Thinking more about what you’ve just said, how do you think Central and Eastern Europe compares with the rest of the continent? Are there things that are unique to the region?

Lucyna: What really distinguishes the region is the pace and dynamic of economic growth. There is also huge capacity and appetite for research and development (R&D) and technology in Central and Eastern Europe, linked to the large, well-educated population in the region, particularly in fields like engineering. And finally, this is a large and important region at the crossroads between the West and the East.

Neil: What is the role of lenders and debt in the infrastructure ecosystem – is the availability of credit a constraint in Central and Eastern Europe?

Lucyna: Credit is available, the issue is usually mainly about how to make a project ‘finance-ready’ or bankable. I believe there is still a need to strengthen the financial system in the region. It is dominated by the banking sector: nearly 90% of the economy is financed by banks. And those banks are generally liquid and hungry for attractive transactions. When you add in multilateral institutions and other local development banks, it’s clear there is no lack of available financing (at least in the near future). But this will change over time as infrastructure portfolios grow and tenors get longer, so this may come up as an issue at a later stage.

What is missing are well-developed and integrated local capital markets – institutional investors and local pension funds could have been far more present than they have been, particularly when it comes to long-term investments. There are a number of green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds out there, but this is all still really in its infancy and would benefit from greater depth.

Neil: How would you summarise the effect of infrastructure in the region?

Lucyna: Infrastructure is a great enabler of economic productivity, but it also has effects beyond that. Good examples are the clean air programmes in the region (with the support coming from the EU). If you look at them, you see that when there are improvements in specific infrastructure such as more sustainable district heating and greater electrification, you end up not just with a more productive economy but with longer life expectancy, better health outcomes and a number of other positive flow-on effects. Irena estimates that the economic value of avoided air pollution in the Central and South East Europe region is estimated at between EUR5bn and EUR20bn per year in 2030. Better infrastructure has broader social impacts leading to greater inclusion. The whole impact is multi-dimensional. Looking forward investing in clean and smart infrastructure will not only provide a boost to short-term growth, but bring longer-term resilience of societies.