Africa: Is the African superpowers’ flu turning into pneumonia

How the mighty have fallen. There is no doubt that the economic fortunes of South Africa and Nigeria, once the leaders of the ‘Africa Rising’ narrative have suffered from adverse external factors, but to many commentators it seems that many of their current issues are self-inflicted. The importance of these two giants to the perception of the African continent amongst investors cannot be over-stated. With around US$600bn in combined GDP, they represent 40% of the Sub-Saharan economy, and have historically secured around 70% of total private equity investment. If they cannot reverse their current growth trajectory, what does this mean for the rest of Africa?

South Africa and Nigeria have several characteristics in common. They are the two largest economies in Africa, they both have a growing consumer class, rising urbanisation, and the potential to benefit from a ‘demographic dividend’. However, both are prone to cycles, exogenous shocks, and share some idiosyncratic political and cultural challenges. Their current problems may have had different points of origin, but both economies find themselves up against strong headwinds today. For investors, this could be both a short term problem as these headwinds place pressure on corporate profit growth, but could also be an opportunity for contrarian investors, particularly those with the ability to take a longer term view!

South Africa

Homegrown or Imported Challenges?

South Africa’s woes are almost entirely homegrown. For years now, the country has struggled with slow growth caused by structural impediments including high unemployment, labor challenges, industrial action, and electricity shortages. Although inflation has largely been kept in check, the currency’s penchant for roller coaster antics has become a widely watched indicator of EM volatility. That said, the volatility, at least in part, reflects liquidity with daily FX trades in the Rand equating to almost 20% of South Africa’s GDP, a very high level relative to other currencies. This certainly drives enhanced sensitivity to exogenous events like changes in the Fed rate, but local factors have still managed to influence volatility, none being more prominent in people’s minds than those linked to the revolving chair in the Finance Ministry.

‘Musical chairs’

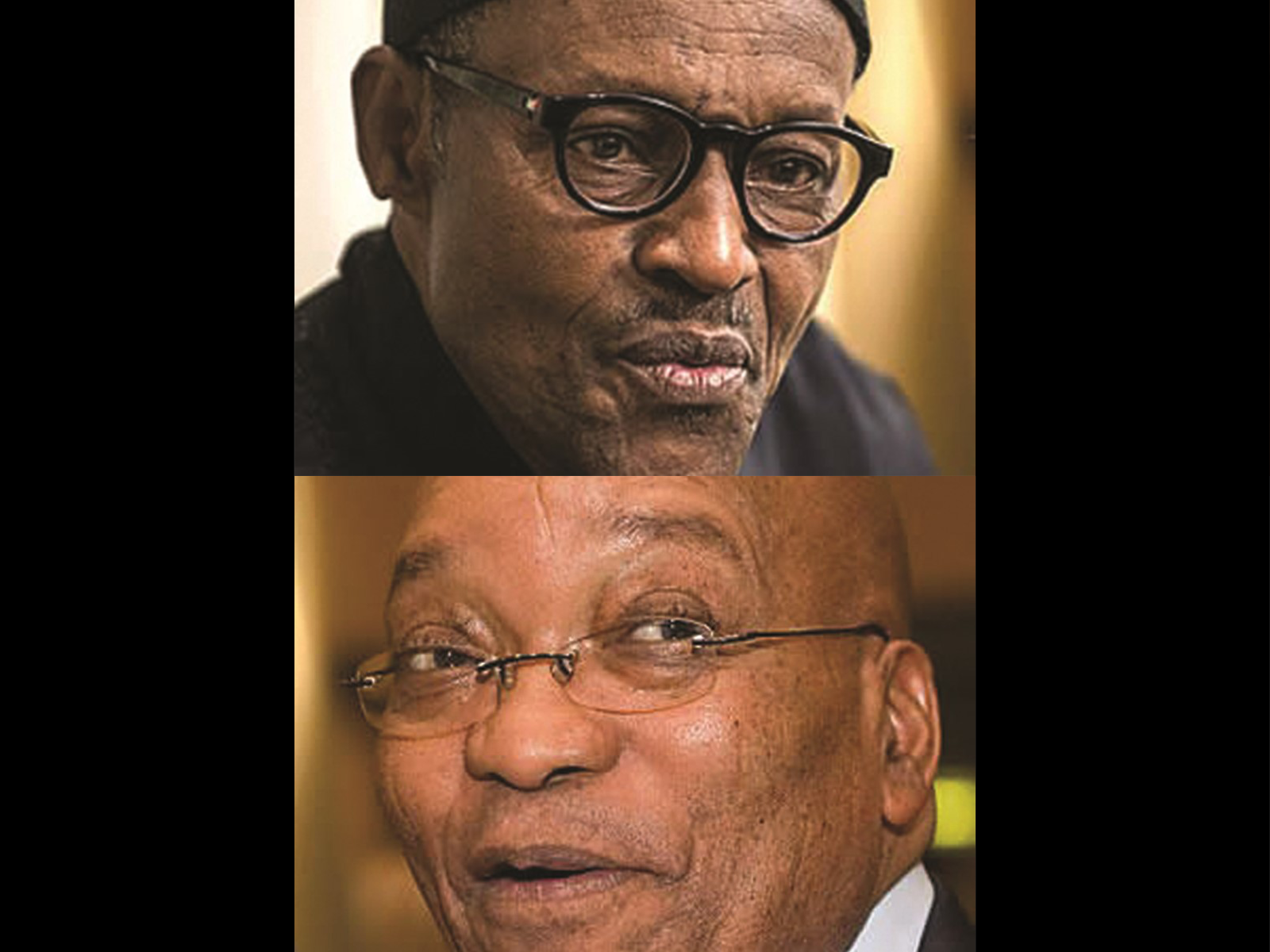

In December 2015, President Zuma replaced well-respected finance minister Nhlanhla Nene with a largely unknown politician, Des van Rooyen. The market reacted in shock with a steep depreciation in the Rand. Three days later and in reaction to pressure from the fallout, Zuma replaced van Rooyen with a previous, well-respected finance minister, Pravin Gordhan. Fast forward almost a year, and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) brings fraud charges against Gordhan, with the timing of the announcement and perceived ‘frivolity’ of the fraud charges immediately questioned, with allegations of political interference both within the ANC as well as from commentators and opposition parties. President Zuma has been accused of seeking unfettered access to the South African treasury – with Gordhan being the one person standing in the way.

Now, in early November, the charges have been withdrawn due to the inability to prove criminal intent, only to be shortly followed by news that Gordhan will be charged again before the end of the year! The new charges will relate to the so-called ‘Rogue Unit’ – a special division set up during Gordhan’s tenure as South African Revenue Service head to investigate tax evasion and other tax-related matters. It is therefore difficult to predict if we could see a new round of finance minister ‘musical chairs’ in the near future in light of recent events.

State Capture’

Adding to the political turmoil in recent weeks has been the much anticipated ‘State of Capture’ report on alleged state graft which Zuma, van Rooyen and minister of Mineral Resources, Mosebenzi Zwane tried unsuccessfully to prevent the release of. The report focuses on the relationship between Zuma and a wealthy business family, the Guptas, who it is alleged had undue influence over the recent ministerial changes in addition to having benefitted from their influence in the award of state company contracts. The report calls for a judicial enquiry and this is likely to be a protracted affair. All of this adds further to the calls from civil society and opposition parties for Zuma to resign or for the ANC to recall him, but at this stage we see limited probability that his hand will be forced.

Rollercoaster ZAR Reaction

The consequence of the Gordhan episode, unsurprisingly, is that the Rand has been ‘oversold’ relative to our fundamental value analysis. Prior to the Gordhan fraud charges, the ZAR was appreciating towards our view of fair value at c. ZAR12-13 to the US$. It slipped with the announcement of the Gordhan charges and recovered on the NPA withdrawing charges. The ZAR strengthened again on the release of the State of Capture report. We can expect to see a reversal again should charges be reinstated or if new charges are brought against Gordhan and, if when the music stops, he is out of a seat. However, the ongoing interplay between the developments around the Gordhan case, State of Capture report, and economic indicators will have a direct impact on the probability of a ratings agency downgrade, something that Gordhan fought so hard to stave off back in June.

Nigeria

It’s More Than Just Oil

Nigeria is experiencing the worst recession in 20 years with Q2 2016 GDP falling c.2% year-on-year. Foreign reserves fell to the lowest levels in 11 years and inflation is at a decade high of 18%. Oil production dropped by 35% from 2.15 mbpd in 2015 to 1.4 mbpd in 2016 due to the impact of militancy in the Southern oil producing region. The economy relies heavily on oil – 70% of government revenues are earned from oil and oil accounts for 90% of exports. The slow pace in diversifying the economy, together with the ongoing oil price slump and a drastic drop in oil production has seen Nigeria suffer a shock with further weakness expected through to the end of 2016 and into 2017.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (‘CBN’) abandoned its US$ currency peg on 20 June 2016, after 16 months of economic deterioration. This was clearly unsustainable and the Naira (‘NGN’) lost over 50% of its value once the peg was removed in June. The Naira is now trading around NGN315 to the US$. This is in line with our view on fair value. However, the NGN is still trading at a significant discount to the official rate in the parallel market, and the differential between the official and parallel market rate highlights the lack of liquidity in the market which has not seen any significant improvement due to rationing by the CBN. Our FX model suggests these are structural liquidity issues rather than representative of the Naira’s fair value, but this is cold comfort for companies and individuals seeking to access dollars in Nigeria.

The country has plans to diversify the economy, to widen its tax base (6% of GDP vs SSA average of 14%), and to increase revenue from other sources to decrease reliance on oil. In addition, planned investments in infrastructure (which will be largely funded by debt), reflect a recognition by Government of the need to restore confidence in the economy and prop up growth. Should the oil price strengthen in 2017 or production volumes return to more normal levels, this would boost reserves and help stabilize the Naira. That said, we see no obvious short term catalyst for a spike in oil prices, making production growth the key driver the Government can influence. How easy it will be to restore public order in the Delta in a period of declining real wages and high unemployment is unclear. The planned infrastructure projects should also improve the ease of doing business in Nigeria and improve investor confidence in what is a challenging market logistically. However, all of these improvements will take time and will require significant public sector investment, suggesting that in the short term, conditions will worsen further as real incomes continue to decline.

So Is the Glass Half Empty or Half Full?

It’s not all doom and gloom for Africa’s superpowers. Despite today’s headwinds, the long-term drivers of investment for both countries remain intact. In South Africa, notwithstanding the impact of political events, economic indicators are offering early signs of a recovery including a decline in the rate of inflation acceleration and potential monetary policy easing. In Nigeria, a recovery in the oil price together with implementation of the government’s expansionary budget which is expected to yield results in 2017 will offer some relief to the economy. Positive effects will then filter through for consumers and into other sectors of both economies. Clearly though, both will continue to cast a long shadow over the Continent into 2017, which may well lead to more attractive asset pricing in markets that are less impacted by the economic factors affecting the local giants but nonetheless suffer from a degree of contagion in investors’ minds.

We have seen demand for quality assets in both markets remain steady. Our recent exit from Tekkie Town (which is subject to regulatory approvals), a shoe retailer in South Africa, and our investment in Azura, a large (459MW) gas-fired power generation facility under construction in Nigeria, are examples of how local knowledge and sector insights can be powerful tools for seeing the value during times of low visibility and high uncertainty.

In 1997 it was the Asian debt crisis, in 2008 it was the global financial crisis, in 2011 it was the Arab Spring. Investing in growth markets will always be punctuated by geopolitical headwinds and global exogenous shocks, but the silver-lining is that this creates opportunities to find high quality investment opportunities. The outlook may be blurred for Nigeria and South Africa as they navigate through their respective sets of issues, but these giants will eventually awaken from their slumber with their long-term fundamentals still intact.