Investors love labels. Developed, Emerging and Frontier Markets are the most common groupings applied to economies, asset allocation and risk budgeting. Like it or not, these labels exist and are widely employed in investment decision making.

Consensus can blur reality and obscure opportunity. Within these major categories, wide differences exist. A global thematic investor like Actis seeks out opportunities wherever they exist. The homogeneity implied by broad categorisation has limited utility in assessing specific country risk. Fortunes have been lost rather than made in pursuit of consensus.

Consensus can blur reality and obscure opportunity. Within these major categories wide differences exist. A global thematic investor like Actis seeks out opportunities wherever they exist.

“Emerging Markets” as a catch-all label is a major culprit in creating misconceptions based around assumed similarity. Covering most of the global population, geography, resource production, and foreign exchange reserves, the 80 countries or more in this bucket have less in common with each other than the 25 or so developed markets. How is South Korea like Peru? Or Estonia and Qatar? Or South Africa and India? Yet they are all lumped into the one classification.

Equally, there are profound structural differences between many developed markets. Resource winners such as Canada and Australia clearly differ from France, Spain and the UK.

How is South Korea like Peru? Or Estonia and Qatar? Or South Africa and India? Yet they are all lumped into the one classification.

These broad characterisations have become increasingly misleading since first employed in the mid-1980’s. In this, the hand of indexation and risk budgeting hang heavy. Today, the idea of a 100-page report on the Nepal stock market as was written in 1992 (top tip Yak and Yeti Holdings) is quaint. More to the point, homogeneity has suffocated opportunity, with a handful of countries representing over 80% of most indices.

Across 80 plus countries, wide differences of opportunity are obvious. Yet common and lazy investment and media shorthand ignores this point. The weakest countries frequently dominate the dialogue. The case of Sri Lanka – a wonderful country with woeful macroeconomics – overwhelms the attractions of India just to the north in the mantra that EM is too risky, too corrupt and unable to deliver returns. ‘Four legs good, two legs bad’ to quote Snowball the pig in George Orwell’s classic “Animal Farm”.

Over the 40 years since the Emerging Markets label was first employed, other taxonomies have been tried. The investment graveyard is stacked with BRICS, MINTS, Next 11, Fragile 5 and other whims. Some struggled because the premise imploded (BRICS), others were more temporal or pejorative (Fragile 5). Most of all, the relentless march in liquid markets towards indexation obliterated incentives to differentiate. Worth noting that even the plethora of single country ETFs attract a fraction of the flows that go to the broader categorisations.

Given this, why bother to distinguish? Is there real investment opportunity in embracing diversity? We believe so.

Actis is a global investor with a particular heritage in the Emerging Markets. We have, as they say, real skin in the game. Our entire investment history – over 70 years, US$ 25 billion capital raised, and 43 countries – speaks to the value of diversity of opportunity. We are used to staring beyond the headlines to spot opportunity, whilst operating a disciplined approach to individual investment evaluation and managing risk.

We are used to staring beyond the headlines to spot opportunity, whilst operating a disciplined approach to individual investment evaluation and managing risk.

Discipline ensures consistent, objective, risk aware decision making. Our footprint is truly global, increasing the need for sub-categorisation as we seek opportunity. Our LP community and other stakeholders ask us to differentiate between countries in a consistent fashion and be able to explain decisions and outcomes using meaningful frameworks. Some of the larger and more diversified asset owners are also seeking categorisations to shape their own strategic and tactical decision making. Hence, we present here our new taxonomy of global investing.

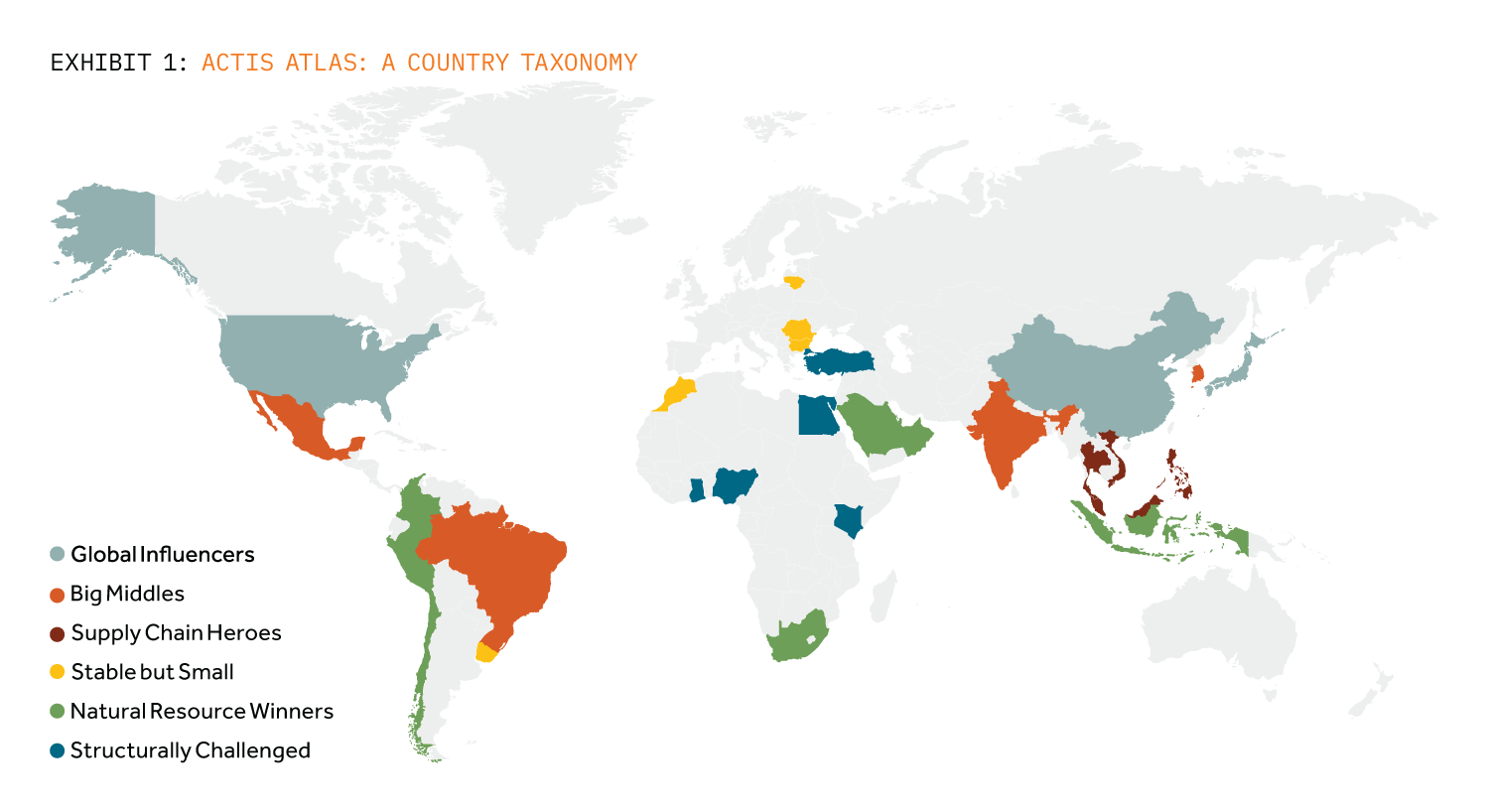

Let’s be clear – we don’t expect that EM or DM will die as labels. We don’t expect the process we have applied to be infallible or immune to criticism. We have applied a limited series of judgements, conscious of the virtue of simplicity over complexity. In consequence, we have placed countries in a single bucket even when they obviously span more than a single category (See Exhibit 1).

In short, this report helps unpack global investment opportunities beyond the two big, over simplistic, labels of Developed and Emerging Markets. We strongly assert that broad brush judgements which have no justification beyond simplicity, do not drive successful investment outcomes for longer term investors. We do recognise that some categorisation is essential to allow for appropriate benchmarking of opportunity and disciplined risk budgeting. We don’t hate labels; we simply think there are too few to be useful these days. Extrapolation can harm your wealth.

This report now falls into three sections. First, we outline our definitions and allocations. Second, in a longer and more detailed section we explain our methodology and provide proof statements. Finally, we summarise a few brief conclusions.