In previous Actis articles, I have discussed the role that both mobilising and then enhancing the productivity of human and physical capital plays in driving sustained economic development. Growing a poor economy with a rapidly growing population and a low initial capital stock is, in theory, relatively easy (though many countries, sadly and serially, fail). However, maintaining growth spurts beyond middle income status has historically been a rather harder endeavour requiring institutional changes conducive to sustainably boosting factor productivity.

No unique recipe has to date been discovered that guarantees economic development. However, successful transitioners have generally provided sufficient macroeconomic and legal stability to mobilise both domestic and longer-term foreign savings, which in turn facilitates increased investments in human and physical capital. An openness to international expertise, trade and more stable forms of capital such as direct investments in the real economy has also invariably been part of the special sauce shorter-term foreign capital flows are more vulnerable to swings in risks appetites and sudden stops such as occurred during Asia’s 1997 collapse or the 1994 Mexican Tequila Crisis).

The plethora of domestic savings and financial repression creates pools of domestic funded long term capital. This is ideal for the great asian infrastructure spend.

Asian economies east of the Indus River have accounted for a disproportionate amount of the successful transitioners. The process was led by post-WWII Japan, followed by the Newly Industrialised Country grouping of South Korea, Taiwan plus the city entrepots of Hong Kong and Singapore, and subsequently China and the original ASEAN Tigers of Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. More recently, other economies in the locale such as India, Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have also joined the party.

On various levels, the global backdrop appears increasingly unfriendly and unsupportive of further material gains. The developed world is grappling with post-inflationary indigestion while a land war is raging on the European continent.

Exhibit 1: Total Fixed Capital Formation as a % Of GDP

*Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and The Philippines

Source: DSG Asia Limited calculations based on Government and other supranational data

Exhibit 2: Inward Foreign direct Investment as a % of GDP

*Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and The Philippines

Source: DSG Asia Limited calculations based on Government and other supranational data

Meanwhile, US-China relations remain troubled and characterised by mutual mistrust and although the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is likely to see a decent rebound over the coming quarters as it exits its pandemic-era isolation, it is struggling with a range of structural growth impediments.

From adversity springs opportunity for the region though. The deterioration in Sino-US relations over the past decade has driven a push for supply chain recalibration, if not quite a full-blown decoupling. This may result – near-term at least – in less efficient and higher cost production, but the countries that can attract such re- locational capital stand to benefit.

As the world emerges from the pandemic, paused domestic capex plans can be resurrected and foreign investor due diligence exercises completed. Economies that are able to enhance their absorptive capacity capabilities, provide a welcoming and predictable investment climate, flexible labour markets and improved infrastructure should be well-placed to boost domestic investment and to also attract stronger flows of inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

The Asian economies surveyed here are, arguably, particularly well-positioned. Savings rates have been consistently elevated over the decades accommodating a higher rate of investment than generally recorded in other parts of the globe (Exhibit 1). For sure, not all investments have been necessarily productive while booms have given way to periodic busts when capital allocation quality has deteriorated. Nevertheless, the region’s longer-term productive capital accumulation has been far from poor overall.

This investment success has been based on both strong domestic and foreign capital mobilisation with annual FDI flows consistently in the 2-4% of GDP range (Exhibit 2). Indeed, the region has traditionally attracted a disproportionate share. Of the more than US$12 trillion stock of FDI UNCTAD records as being deployed to developing countries, developing Asia has accounted for around three-quarters, half of which has gone to China.

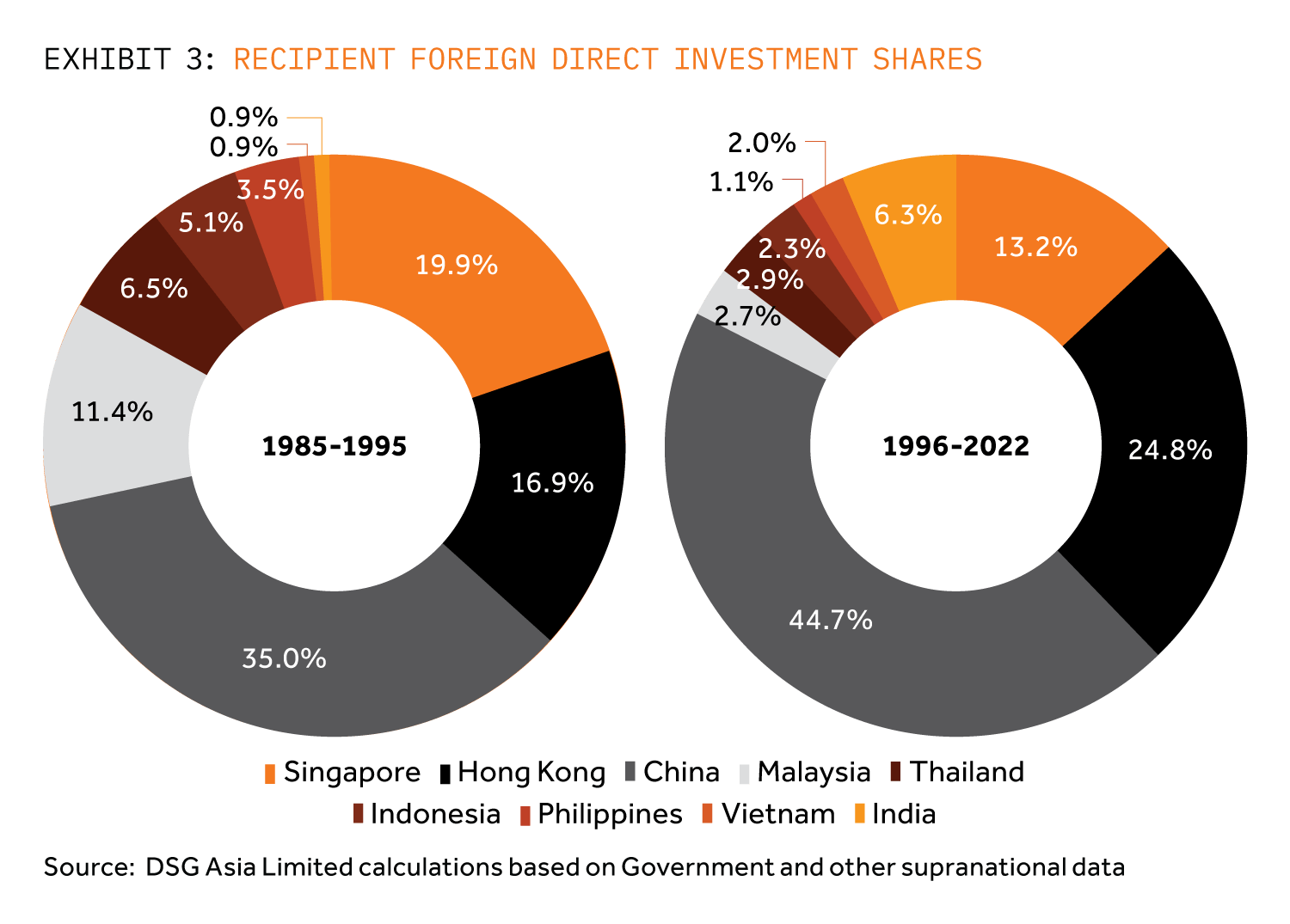

The ASEAN Tigers initially led the way in the 1980s accounting for a quarter of disbursements to the region (Exhibit 3). However, costs rose and excesses increasingly accumulated during the early-1990s at a time when China was accelerating its own reform and opening- up processes and could start to offer real scale. Hence the centre of FDI gravity shifted further north, albeit post the 1997 meltdown, ASEAN has once again started to receive sizeable foreign capital disbursements alongside Vietnam and more recently India.

It seems fair to assume that given the frigid state of great power international relations, the burgeoning trend of the past half- decade to recalibrate supply chains to make them less dependent on single suppliers will only continue. Physical resources can be somewhat more fungible with a (painful) lag but disentangling highly-complicated manufacturing supply chains is a costly and far-from immediate endeavour. Moreover, no other developing country can, at this juncture, match China’s sophistication and scale (nor the attractions of its internal market).

Nevertheless, if even a tenth of the productive capacity of the PRC – a number consistent with various foreign chamber of commerce surveys – seeks to relocate over the next decade, this would represent a huge amount of capital for smaller economies to digest. Hence the need to concomitantly upgrade infrastructure, logistics and energy capacities that do not trash the planet. Needless to say, these are all areas of Actis expertise.

More immediate cyclical challenges remain. The PRC’s re-engagement with the outside world should provide China’s neighbours with a decent enough cyclical demand boost – trade, education, tourism and commodities – which can help to put a floor under an already contracting export growth profile.

Furthermore, although fiscal deficits, understandably, widened across the region in recent years, public debt metrics remain almost universally manageable, foreign borrowing ratios are well shy of their danger zones, and currencies are generally cheap. Finally, balance of payments stresses are largely absent too, albeit the rise in energy costs has been somewhat uncomfortable.

Taken together, Asia still has the potential to grow faster than the rest of the world even if growth differentials narrow as trade shares rise. Equally the plethora of domestic savings and financial repression creates pools of domestic funded long- term capital. This is ideal for the great Asian infrastructure spend provided that government allows the private sector

to earn adequate returns and can absorb inflationary risks.