From being one of the poorest nations with GDP of less than USD5bn1 in 1967, Korea has grown rapidly to become the 11th largest economy in the world with 2017 GDP of over USD1.5tn. But the successful model of export and investment led growth that has driven this progress faces new challenges, and the rapid growth of the Chinese economy has threatened Korean pre-eminence in its key manufacturing industries including electronic displays, shipbuilding, mobile phones, steel, and even semi-conductors and automotive. Hence, there is now a need for a new growth model to foster not only export-led but also domestic growth to continue to improve quality of life for Koreans and to make the economy more robust against the volatility of a world pushing back on globalisation.

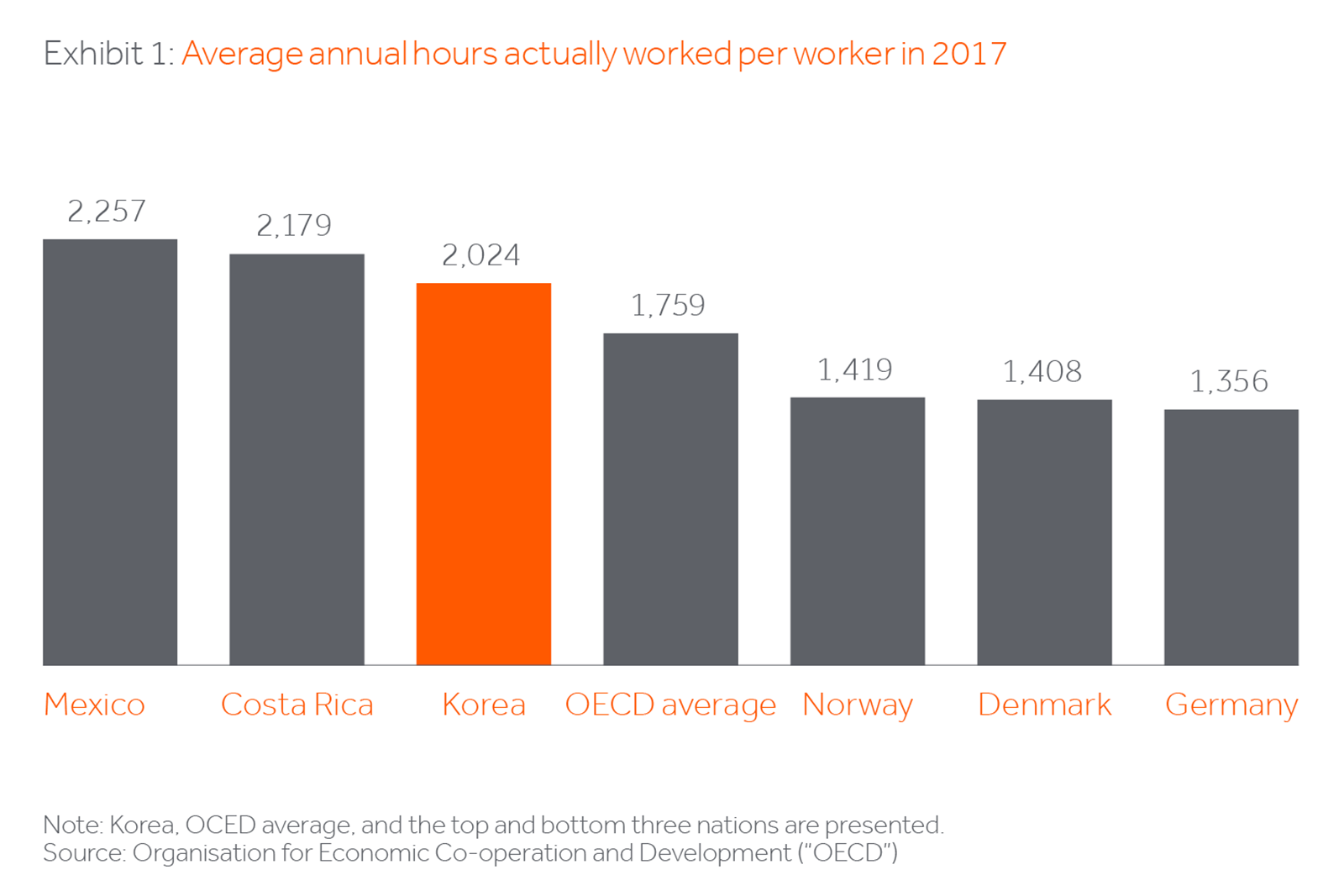

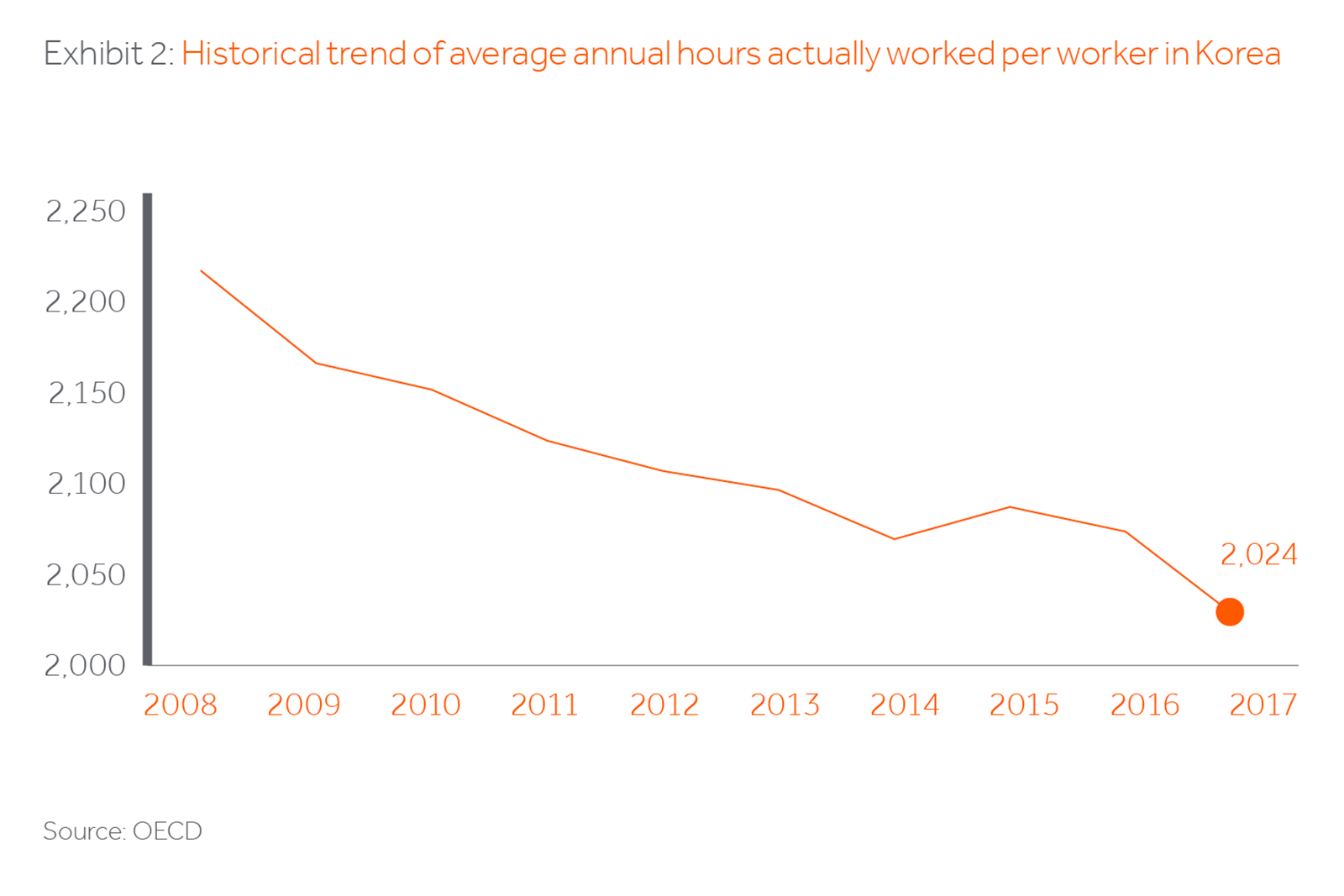

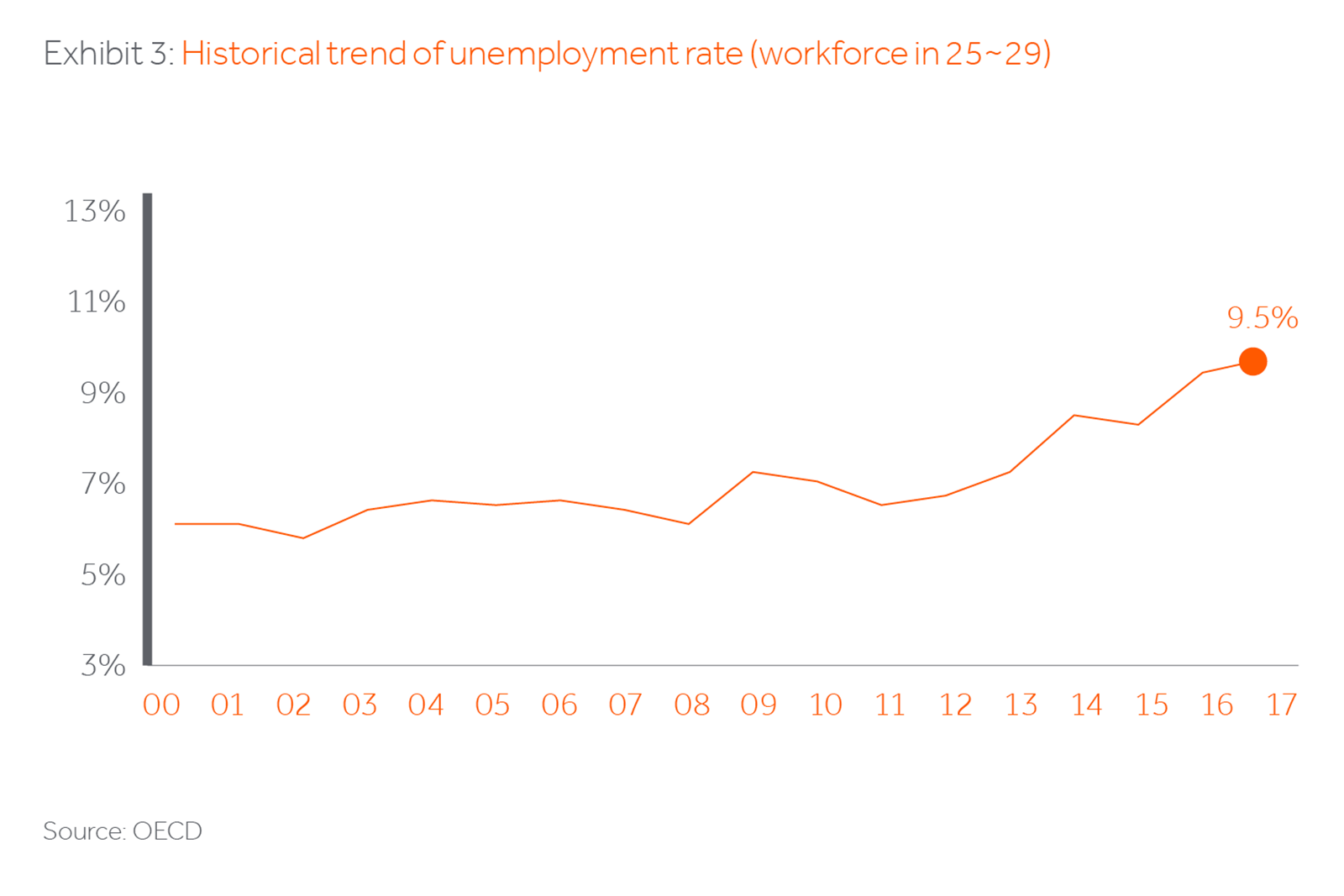

President Moon’s administration has been focusing on a wide ranging agenda aimed at improving growth potential through deepening social and industrial reform. Measures taken include boosting youth employment, supporting productivity through introducing a 52-hour, 5-day work week system, relaxing regulations and rules in various industries, encouragement of the birth rate by creating a more comfortable environment for younger generations to get married and raise children, increased public housing supplies and tighter regulations on multi-housing owners to cool down the over-heating housing market. The new regime has also expanded its spending on welfare of the retirees and the poor under its slogan of income redistribution.

However, this ambitious agenda faces challenges. One of the main challenges is associated with the rapid increase in the minimum wage as a part of the regime’s income led growth program. This is having a significant impact on individual proprietors and small companies that depend on minimum wage earners because these employers cannot easily pass the cost of the higher wage onto their customers.

In parallel with these changes, there is an ongoing shift in household priorities from saving to spending. Unlike older generations whose top priorities were thrift and saving, younger households focus on investments for their future including education and housing. An expensive and inefficient mortgage market consequently contributes to the lower savings rates we observe.

Korea country profile: quick facts

- Area: 99,720km

- Capital: Seoul

- Population: 51.8 million (27th, as of July 2018)

- Growth (%): 0.4% (2018E)

- Median age: 42.6 years (2018E)

- Unemployment rate: 2.7% (as of Jun 2018)

- Youth unemployment rate* (as of Jun 2018)

- Birth rate: 1.17 (2017)

- HDI**: 0.901 (very high, 18th, 2015)

- GDPA: USD 1.53 trillion (28th, 2017)

- Growth (%): 2.9% (2018E)

- GNI per capita: USD 28,380 (28th, 2017)

- GNI per capita (PPP): USD 38,260 (29th, 2017)

- Industry as % of GDP: 39.2%

- Service as % of GDP: 58.7%

- Exports as % of GDP: 44.2

*Economically active population who is 15 to 29 years old **Human Development Index / Source: World Bank, Central Intelligence Agency, United Nations, Statistics Korea, Bank of Korea

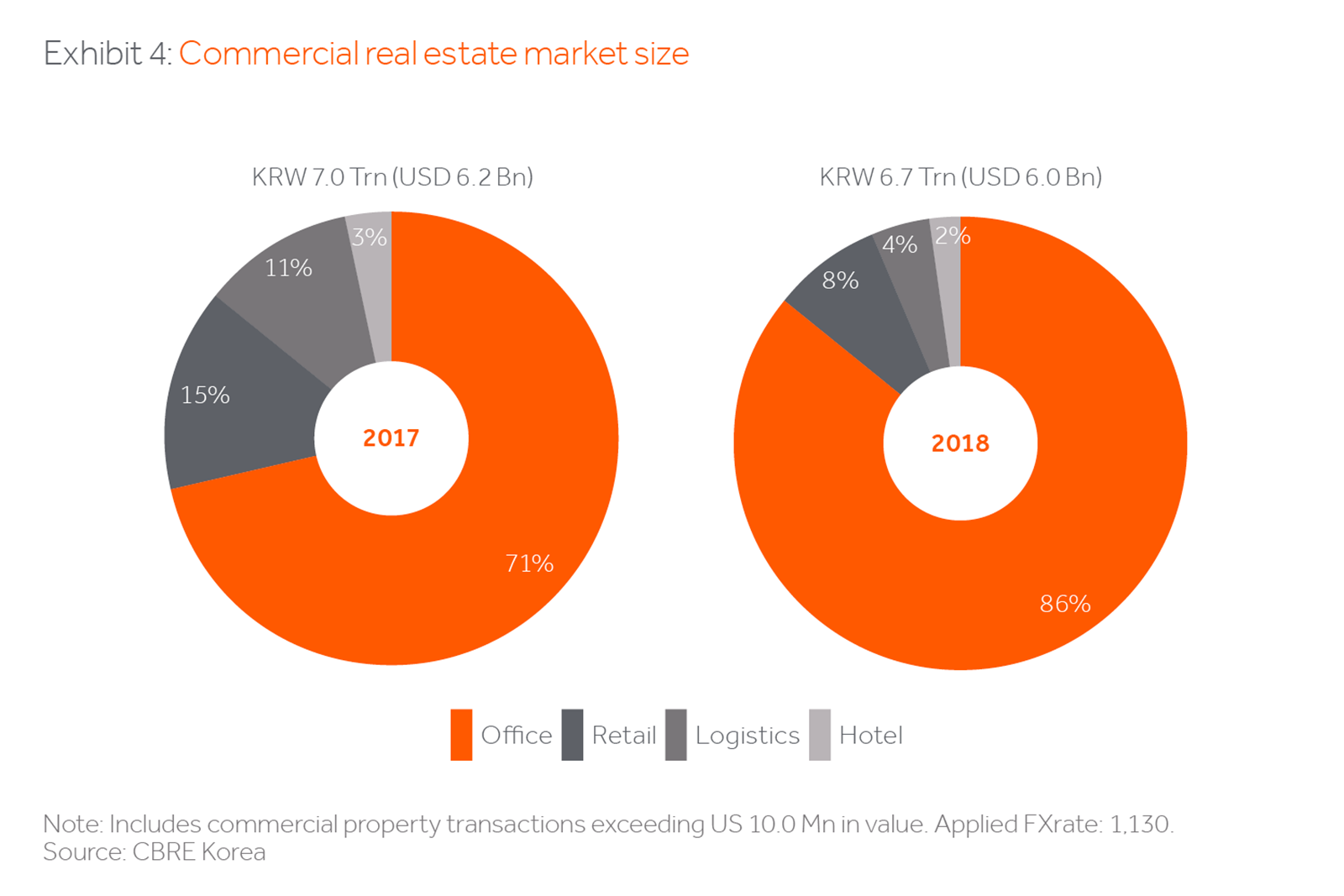

From our perspective as long term investors in the Korean real estate market, the lack of supply of high quality property provides us with investment opportunities at least attractive as those we see in other Actis markets. In the past, when supply was the priority, the model was to provide properties as cheaply and as quickly as possible. However, this has had its inevitable consequences, meaning many properties located even in the most prime areas are now deteriorating and are unfit for purpose. Apgujeong-dong, which is now one of the most prestigious residential zones in Seoul, was developed from farmland in the 1970s and is now hitting a major refurbishment cycle.

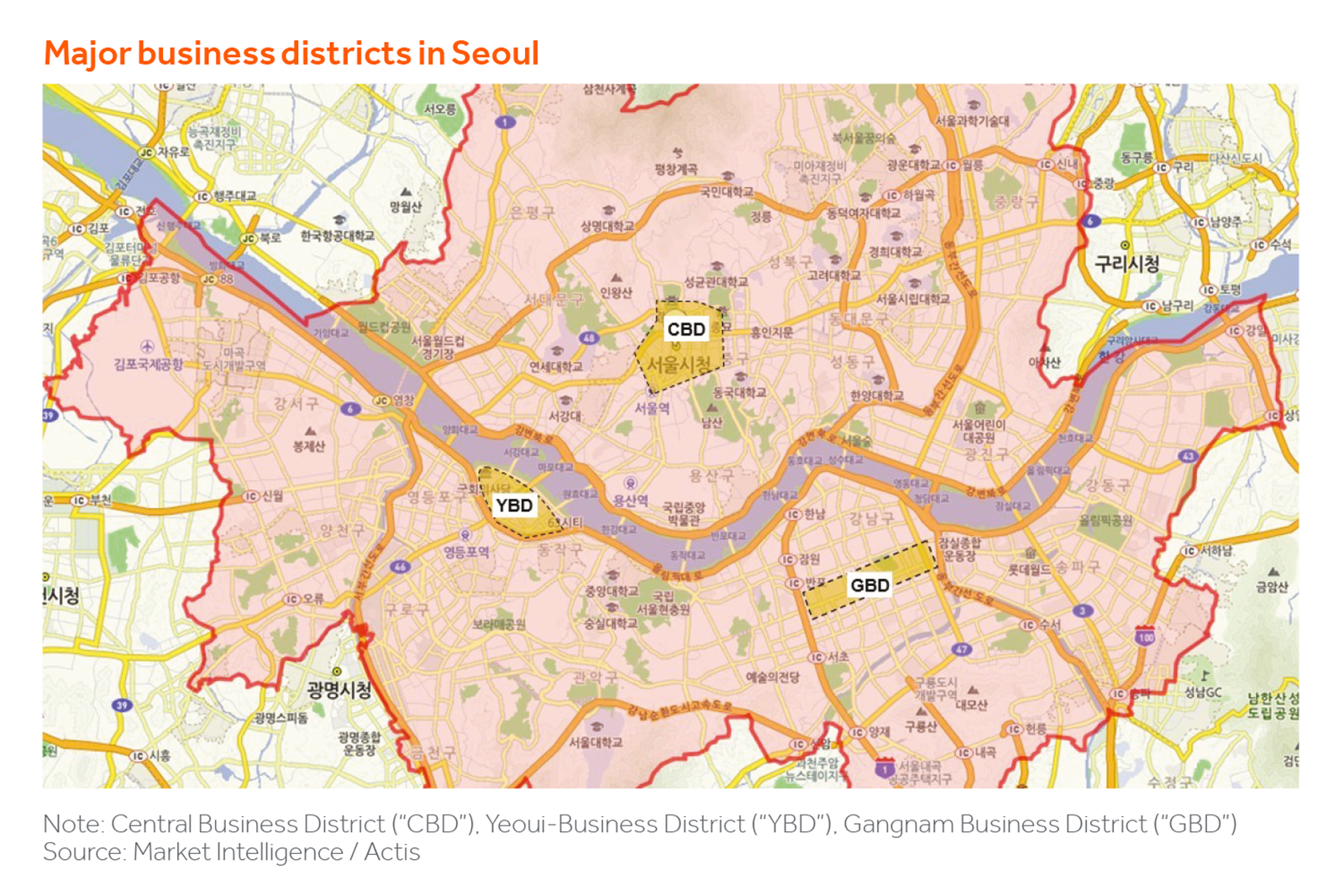

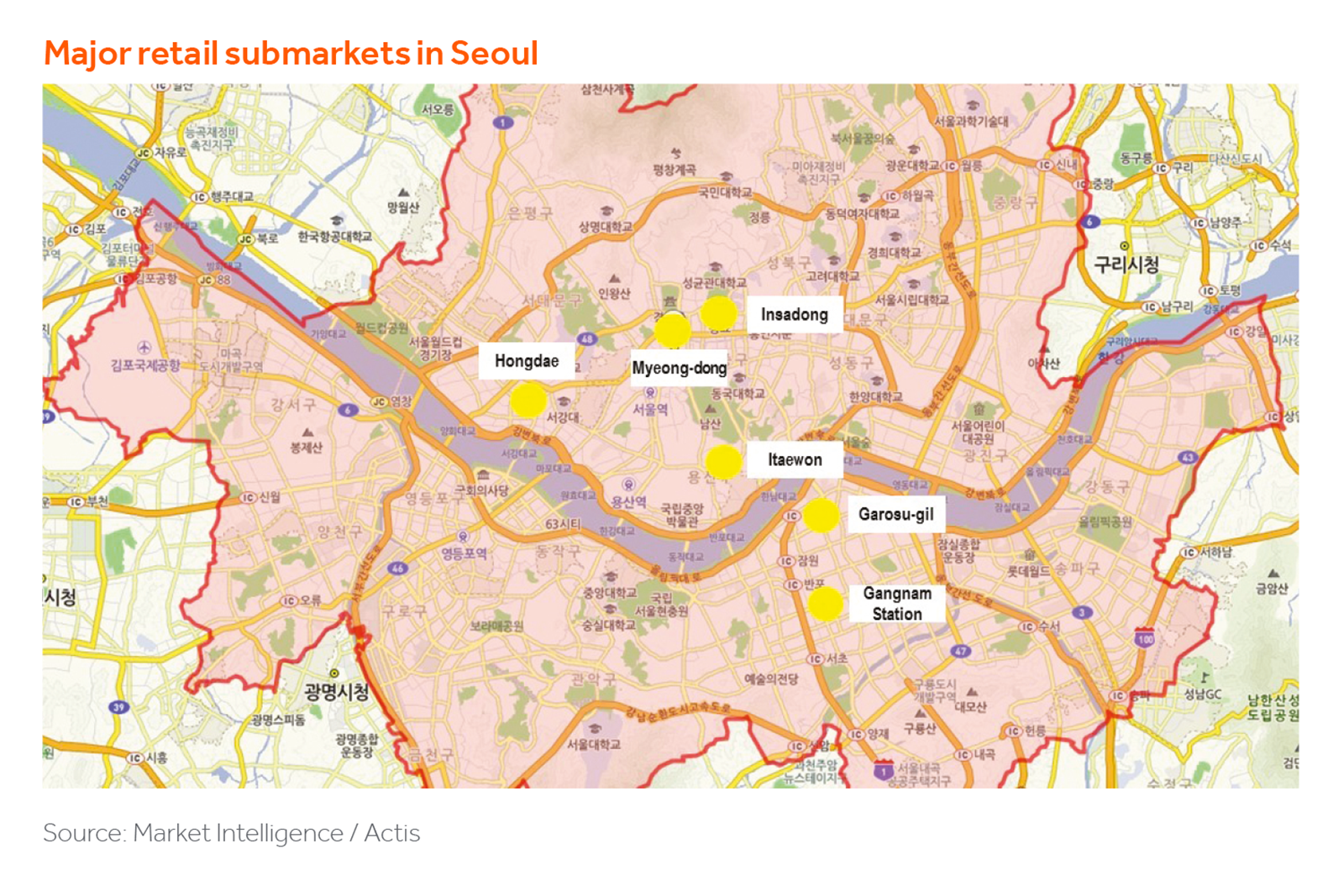

This mismatch between demand and the quality of existing supply is largely mirrored across all types of property – retail, offices, hotels and industrial, as the sophistication of end user demand has evolved faster than quality of the existing assets. As a result, needs for redevelopment or renovation of such unsatisfying properties have continued to grow. This trend is most evident in Seoul, and the focus of our business has always been and is likely to remain Seoul for the foreseeable future.

And whilst the rapid policy-driven additions to supply seen in earlier cycles have contributed to this issue, barriers to institutional investment in the asset class have also had an impact. Up until the mid-1990s, there was no concept of an indirect real estate investment vehicle. The only practical way to make an investment was direct asset purchase by companies or individuals, which resulted in heavy tax consequences. Hence, properties were mostly owner occupied during this era. However, this was changed after the Asian crisis in 1997, when the government introduced an indirect investment mechanism that offered unprecedented tax benefits. This new model was a part of the government’s effort to increase foreign currency reserves by attracting foreign capital and to boost the rapidly shrinking domestic economy by encouraging growth of the real estate market. Creating instruments such as Project Financing Vehicle (“PFV”), Real Estate Fund (“REF”), and Real Estate Investment Trust (“REIT”) made real estate a major investment asset, as it opened up the market to foreign institutional investors that were quickly followed by newly emerging domestic institutional investors.

The Asian crisis also contributed to the advent of the current development model. Prior to 1997, most development had been led by construction companies using their own equity. However, most construction companies faced severe liquidity problems during the crisis, and were forced to stop making long term equity commitments and instead focus on cash flows generated by construction activities.2 Their role in the market has since been filled by small local developers.

This model has been in place for the past twenty years and has contributed to the evolution of a number of characteristics unique to the Korean market. First, most development properties are strata-titled because local developers have insufficient equity capital to complete a full site development and must rely on interim cash inflows generated by presales.3 Second, most of these strata titled buildings were poorly built and managed by separate owners leading to accelerated dilapidation. And finally, the control of development projects in essence remains with construction companies because local developers cannot raise debt capital without credit enhancement and a payment guarantee from the construction companies. So you have a market where investment capital is fragmented and local developers struggle to extend their role beyond title aggregation and securing permits and approvals. Last but not least, institutional investors cannot find sufficient projects to meet their investment appetite because there are simply not enough quality assets, and yet demand for institutional quality cashflows keeps growing.

The Actis Asia Real Estate team developed an institutional development model to try to take advantage of these characteristics, which we refer to as “build to core”. In essence this involves working with high quality operating partners locally to create core assets that will appeal to institutional investors both domestically and internationally. Two recent hotel development projects, in which we invited a top local operator (Shilla – a subsidiary of Samsung Group4 ) to partner with us as the master lessee, providing both a minimum rent guarantee and an assurance of quality for the market, evidence this success, with both attracting strong demand from domestic institutional investors, leading to an exit by selling the assets to the two largest domestic institutional investors, National Pension Service (“NPS”) and Korea Investment Corporation (“KIC”), respectively. We are currently engaging in the development of a mixed-use hotel and retail facility in a core location through a JV partnership with a major local retail operator (GS Retail)5 that will also operate the facility backed by its minimum rent guarantee. This is a strategy that local developers cannot imitate given both liquidity constraints, but also the lack of relationships with key corporate partners in the market.

And one other feature of the Korean market is worthy of note, particularly to those more familiar with our African and other Asian markets. When we commit to a construction contract with a delivery date and a budget, standard Korean practice is for the contractor’s commitments to be met to the letter, to the nearest Won and to the hour. Not something our colleagues elsewhere in the real estate business often enjoy.

2 This is largely the same even nowadays except a few cases where such development projects are deemed to be extremely profitable with no land title aggregation issue or supported by the government.

3 Developers are allowed to initiate strata sales in parallel with construction commencement. However, the ownership title can be transferred to the buyer post construction completion. Hence, once the buyer signs a purchase contract, he/she is required to place an initial deposit simultaneously (typically equivalent to 10% of total purchase price), after which the buyer periodically makes interim payments (typically up to 50% of total purchase price). Post completion of the construction, the buyer makes a final payment for the title transfer (typically within 1~2 months post completion).

4 Hotel Shilla Co., Ltd (“Hotel Shilla”) is the top local hotel brand, which is a subsidiary of Samsung Group. Previously known for a five star hotel brand, the company has actively expanded into the business hotel segment and is currently operating 13 hotels across Korea. 5 GS Retail Co., Ltd (“GS Retail”) is a major local retailer and a subsidiary of GS Group, which is another major Korean conglomerate focusing on energy, construction, and retail businesses.