The Karaoke Presidency

Taking office on January 1st 2019 Jair Bolsonaro is Brazil’s third President in less the official four year-term mandate. Japan’s frequent leadership changes of the last two decades deserved the title Karaoke government-everybody can have a go. Brazil’s new President owes his election in part to the political chaos of the last few years which allied with a deep recession has fuelled a desire for change. Yet despite the change of face the nation’s problems and opportunities remain unchanged and deep set.

How we arrived here

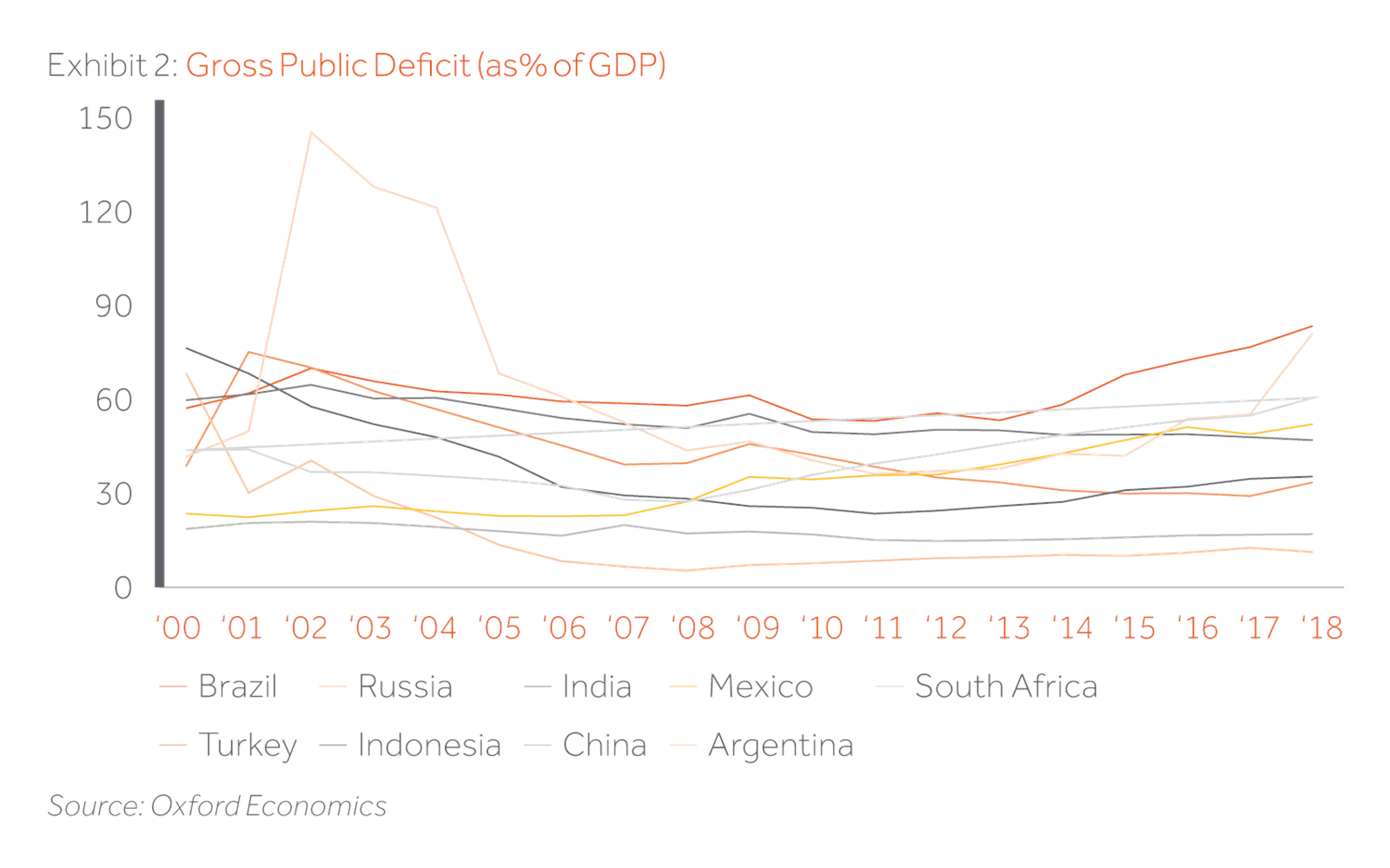

Its worthwhile briefly rehashing the last three years if only to understand why Brazilian electors are so focussed on changing the leader. Within two years of her 2014 re-election Mrs Rousseff faced impeachment arising from the unprecedented corruption scandal surrounding her predecessor and mentor Lula. With Dilma impeached and her vice president Michael Temer stepped up, launching a transformational plan focussed on reducing government spending, privatising unprofitable state owned enterprises and promoting social security reform. This hopeful start though which included strong congressional support was wrecked by the May 2017 allegations of Temer’s involvement in the Car Wash scandal. The consequent loss of support led to a period of inertia which dominated the remainder of his Presidential term. Meanwhile as a backdrop the country suffered a severe recession with GDP contracting by over 8% during the 2016-17 period,13 million job losses, an inflation spiked at 11% and a climb in public indebtedness from 60 to 80% of GDP.

The Electorate Answers Back

Deeply disillusioned Brazilians headed to polling stations on October 21st and 28th to elect lower house seats, 1/3 of the senate, state governors and a new president. The electorate delivered a damming rebuke to the status quo. Nearly 50% of Lower House members have changed, the biggest turnover rate in the last 20 years, only eight of 32 Senators seeking re-election survived and of course Bolsonaro a polarising figure was elected to the Presidency. Brazil following Chile (Sebastian Pinera), Paraguay (Mario Benitez) and Colombia (Ivan Duque) in choosing right wing government in part because of economic failure or disillusionment.

The new man and his finance guru

Brazil’s new leader first emerged in the 1990’s as a member of the Lower House where he has sat now for 28 years. During this time, Bolsonaro a retired military officer adopted a conservative position on social affairs and a centre-left bias in economic affairs (of which he protests limited knowledge). He voted against privatisation and the Real plan designed to combat rampant inflation yet later on supported the Labour reform and public spending caps proposed in the Temer administration, signalling a shift towards the right which later became the motto of his Presidential campaign.

Bolsonaro’s presidential ambitions surfaced in 2016 when Dilma’s impeachment allowed air time for those disillusioned with the political community. His espousal of conservative social policies and zero tolerance for corruption quickly attracted political support, becoming a social media celebrity. In turn this popularity caught the attention of Paulo Guedes, an economist from the University of Chicago with a distinguished financial sector resume including being a founder of BTG Pactual a leading local investment bank and later on as a private equity player investing in education. Between them, Guedes and Bolsonaro, devised a libertarian market friendly economic plan focussed on reducing the size of government and tackling fiscal deficits through reform and privatisation.

A new style election and line up

The election itself was marked by high turnout and heightened use and awareness of social media-over 53% of Brazilian adults use social networks according to 2017 estimates from the Pew Research Centre. In the election there was clear evidence that social media was highly effective in gathering votes at all levels. Bolsonaro had only 34 seconds of TV time yet gathered over 55 million votes via social media. The new framework to control election corruption and spending saw the winner spending only R1.5 million on his candidacy in contrast to the R34m of the runner up and the R1.5 billion spent to elect Dilma including corruption practices unveiled by Car Wash.

‘Bolsonaro had only 34 seconds of TV time yet gathered over 55 million votes via social media.’

Particular focus has fallen on the Guedes team who will shape economic policy. They include Joaquim Levy also from the University of Chicago who was Chief Financial Officer of the World Bank and Minister of Finance during Dilma’s second term leaving prior to the impeachment process. Mansueto Almeida,an MIT economist, has been retained as Secretary of the Treasury and Roberto Campos Neto formerly Head of Treasury for Santander Bank has taken over as President of Brazil’s Central Bank (note there is a state-owned bank called Banco do Brasil that is a different institution).

Currency and financial markets have initially at least liked what they see with the real rallying sharply to apparently overvalued levels below 3.8 after the election and the Bovespa index exceeding its previous record . Bonds too rallied with the sovereign spread contracting initially by 50 basis points despite declining sentiment towards emerging markets.

How long a honeymoon?

Paraphrasing Ronald Reagan,’it’s the economy stupid’ answers the question. The good news is that inflation expectations are well anchored allowing some room for manoeuvre on the monetary front. There is also some modest recovery in domestic demand, always the driver of the economy. Against this the Institute of International Finance, a leading research institution believes that it is rare for an Emerging Market country to recover lost output and growth rates for 8-10 years after a recession of the severity experienced in 2015-16. In turn this puts the spotlight on fiscal imbalances with a yawning and growing social security deficit driven by an ageing population and decades of under provision. Barring structural reform succeeding and given potentially anaemic growth the chances of government debt rising sharply from an already elevated 80% of GDP are material. Putting this in perspective, the tensions between Italy and the EU over a 2.4% fiscal deficit would be met in Brazil with cries of delight with a deficit nearly 2.7 x larger.

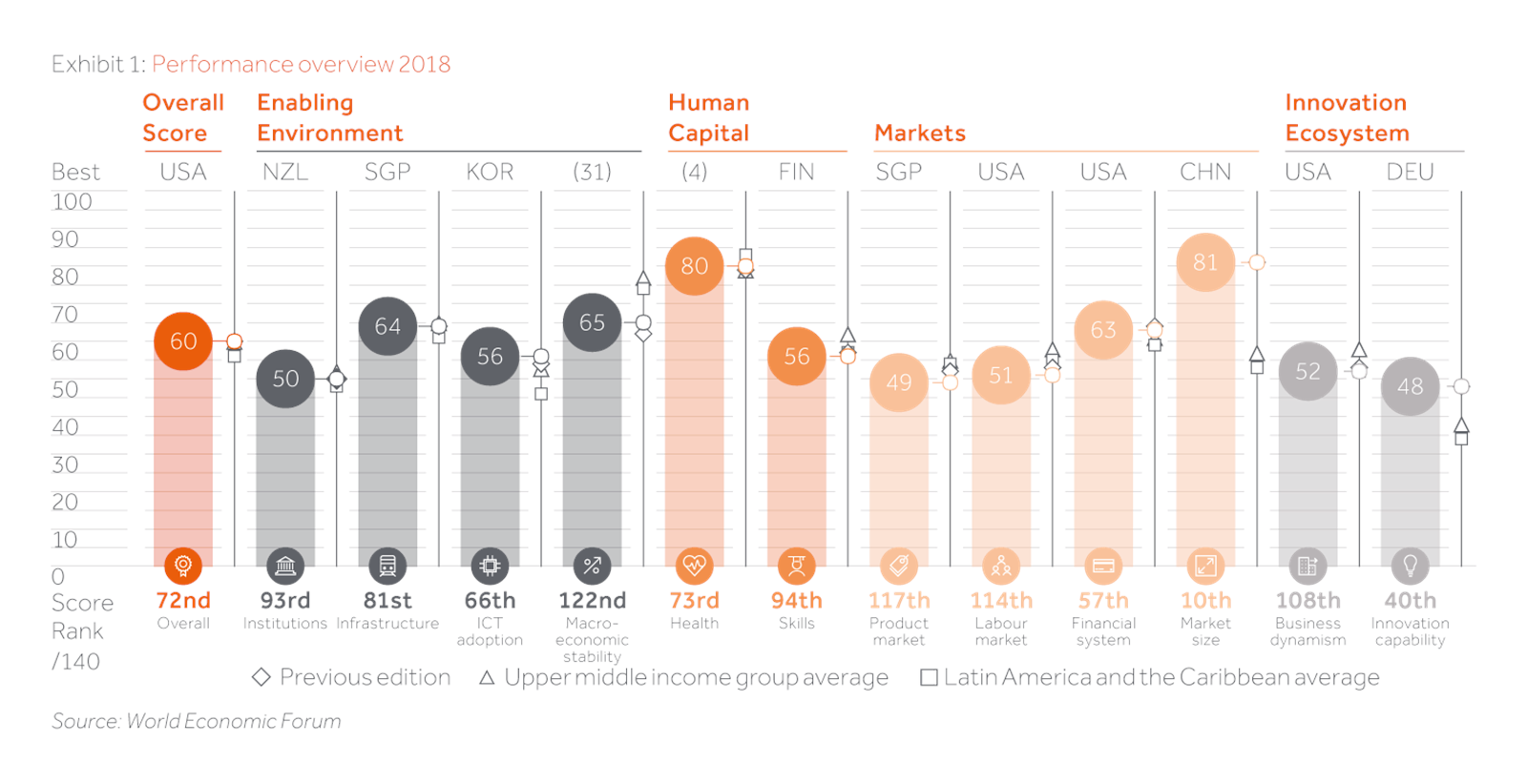

Raising productivity is essential to delivering sustainable long-term growthrates sufficiently and to avoiding a debt trap. The Lula/Dilma legacy is inward looking as far as trade relationships and therefore increased investment and productivity are concerned. The number of state-owned companies-418- is the highest in the OECD which has crowded out investment in areas like infrastructure and education. This is reflected in Brazil’s lowly ranking in a series of world business metrics.

Matters are hardly helped by the external environment with Argentina in recession and China’s changing growth agenda away from capital intensive led expansion. On the other hand Brazilian exports to China expanded in 2018 at a faster rate than before.

Long-term investors are still cautious on Brazil despite the short-term recovery signs, the heightened volatility observed in EM currencies markets doesn’t help too. In the local infrastructure market, even though the fundamentals are supportive, the availability of sources for long-term financing is a question mark with decreasing activity from development banks coupled with an incipient local capital market traditionally focused on short-term, in this context the anchored inflation and maintenance of low interest rates are key. Consumer-driven investment theses are also dependent from more sustainable and concrete actions able to promote sustainable growth and boost productivity, at the moment investors haven’t removed the perception that recent recovery may have been a chicken flight.

The Final Word-Carnivals don’t last forever

Time is short for the Bolsonaro team not least to harness the support currently enjoyed in Congress. Bolsonaro’s political ability to preserve such support will be detrimental for the success of his mandate, moving away from the polarising narrative that dominated the Presidential campaign and adopting a conciliatory approach.

The two key areas-tackling the fiscal deficit and boosting productivity are inter dependent. Short term fixes arising from privatisation won’t solve the longer-term growth puzzle. Lack of success would see a deep fiscal challenge as the Bolsonaro government seeks to accomplish reforms and attract the investment essential to solve deep seated productivity problems.