More than a decade has passed since then-Premier, Wen Jiabao, remarked that the Chinese economy was “unbalanced, uncoordinated, unstable, and unsustainable.” Yet subsequently Beijing has seemingly lacked the political stomach to follow through on regular statements of rebalancing intent. In the interim, China has become a highly-indebted economy, still heavily reliant on fixed investment and government expenditure emphasising the primacy of the state over the private sector.

As a still-middle income country, China needs to continue to invest significantly for its future and retains ample potential to further boost productivity. Nevertheless, its borrowing binge over the last decade has driven indebtedness to developed world levels, and seen the external surplus cushion all but disappear. Meanwhile, in the context of ongoing and likely persistent trade tensions, 1 the strong trade tailwinds of the past threaten to shift structurally more to the fore.

Arguably this backdrop gives the authorities a strategic opportunity to introduce productivity-rejuvenating reforms under the cover of blaming nefarious outside influences for the slower interim growth that would likely transpire. However, should the appetite for even a modicum of pain remain weak, then a doubling-down on debt-fuelled investment-led growth cannot be ruled out with attendant risks to financial and currency stability. Whichever road Beijing chooses will have major impacts beyond its shores with correlations of China to Asian growth running around 0.8.

Economic growth can be delivered by employing an increased quantum of different factors of production (land, labour and physical capital), improving the productivity of these factor inputs, and finally by leveraging them up. In the immediate decades following the introduction of the Open-Door Policy in 1978, China was exceptionally successful in delivering on the first and second of these paths. The last decade has seen far more of a focus on the third. The period from 1978 to the early 1990s was largely a story of recovery and factor re-mobilisation in the aftermath of the chaos – economic and societal – unleashed by Mao’s Cultural Revolution. During this time, it took only a single unit of additional credit to deliver a single unit of nominal GDP.

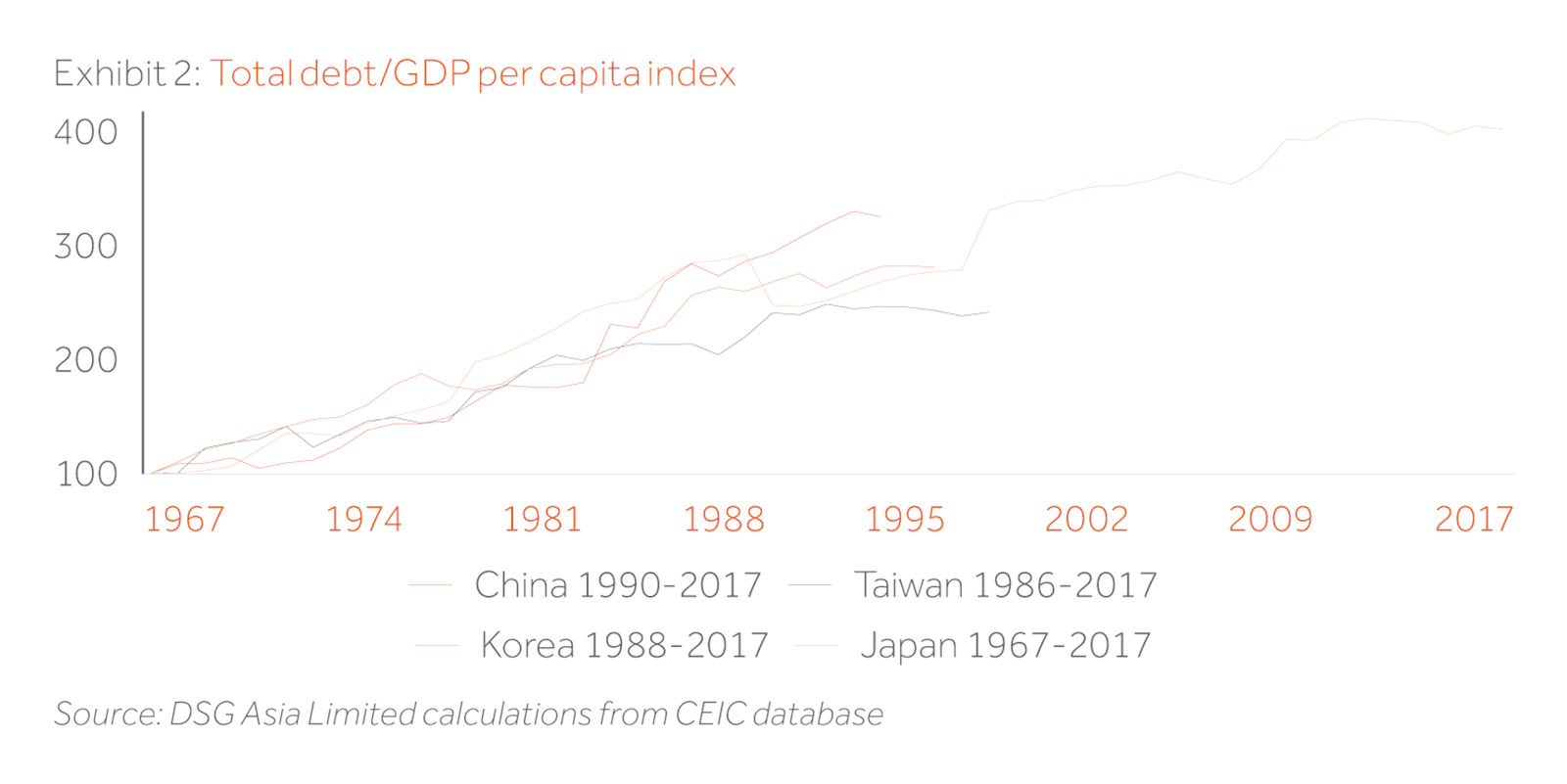

The decade-and-a-half from 1994, largely under the auspices of Premier Zhu Rongji, witnessed accelerated reforms and financial deepening, yet credit intensity only rose towards 1.5:1. However, post-2008, it has required three units of increased credit to generate an incremental unit of GDP. China’s response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis was a massive twin monetary and fiscal stimulus programme which successfully headed-off a severe economic downturn, but left the country with significant industrial overcapacity and high levels of indebtedness. For the next half-decade, the authorities attempted to rein in excesses but when growth again threatened to slow in 2015, the monetary and fiscal taps were again opened wide. This propelled debt ratios beyond those racked up by Japan in 1989 but at a stage of development more akin to Japan’s in 1970 (the chart above incorporates both variables).

Such comparisons can never be exact. Nevertheless, it seems questionable whether the financial system, in isolation, can finance growth from today’s levels of indebtedness in the absence of a recommitment to economic reforms aimed at rejuvenating productive potential. This is far from impossible since we must recall that China has generally found the capacity to deliver over the past four decades when faced by potentially existential challenges. Whether Xi Jinping’s re-emphasis of Party- and state-led control provides the mechanism to deliver such a productivity rejuvenation remains to be seen.

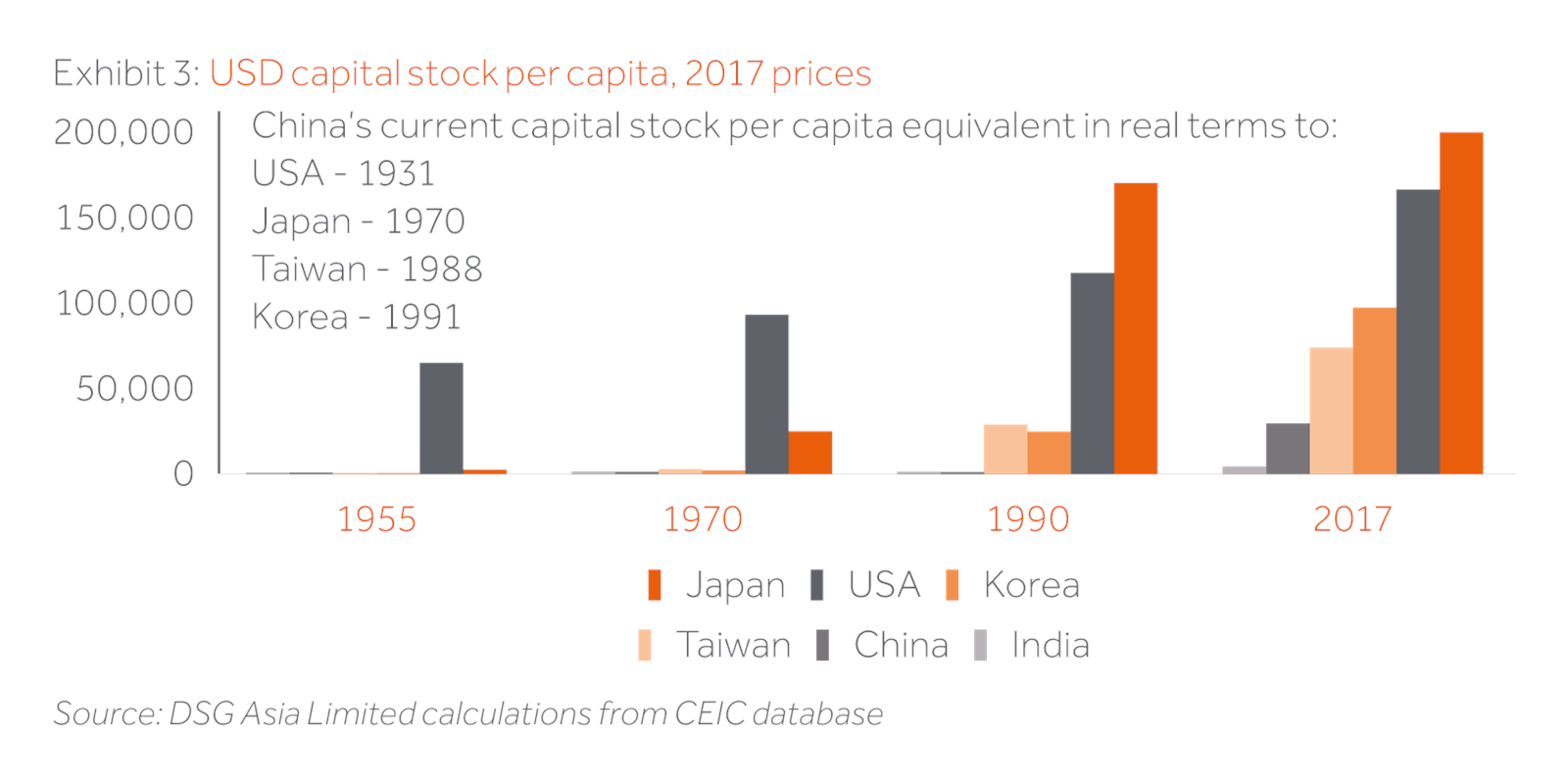

The media may be awash with stories of wealthy Chinese investors buying up global assets Nevertheless, although a small percentage of 1.3 billion people translates into a large absolute number of rich investors, China remains overall a rather poor country. In constant US dollars, per capita income and wealth are only at levels achieved in Japan in 1967, and in 1986 and 1988 in Taiwan and Korea, respectively. It is a similar story with per capita capital stock – the value of a country’s physical infrastructure, plant and equipment. A first-time visitor to Beijing, Shanghai or Shenzhen may dispute the comparative figures charted above, but one does not need to travel too far outside of the major urban centres before one soon encounters areas of significant poverty.

Furthermore, as a country matures, the composition of the desired capital stock also changes as the onus shifts from initial accumulation, to productivity and general welfare enhancing investments. Constructing a first road or railway to a remote location will boost productivity and connectivity considerably. Building subsequent duplicate links will deliver, at the margin, rather less of a bang for the renminbi. Middle income countries with decent core infrastructure extract superior medium-term benefits from investing more in higher quality housing and local transport, as well as better education, healthcare and environmental protection. The downside is that such “softer” investments deliver less of an immediate boost to headline growth than do major infrastructure and heavy industry projects.

Beijing is of course not unaware of these challenges and has unveiled a regular flow of policy initiatives and exhortations over the past two decades in an attempt to rebalance its economy away from a reliance on investment, heavy industry and exports, and more towards consumption and services. Some progress has been made for sure but the unwillingness to officially recognise that such a transition has never been achieved elsewhere, absent an extended period of slower headline growth, has remained a fundamental and ultimately overriding contradiction.

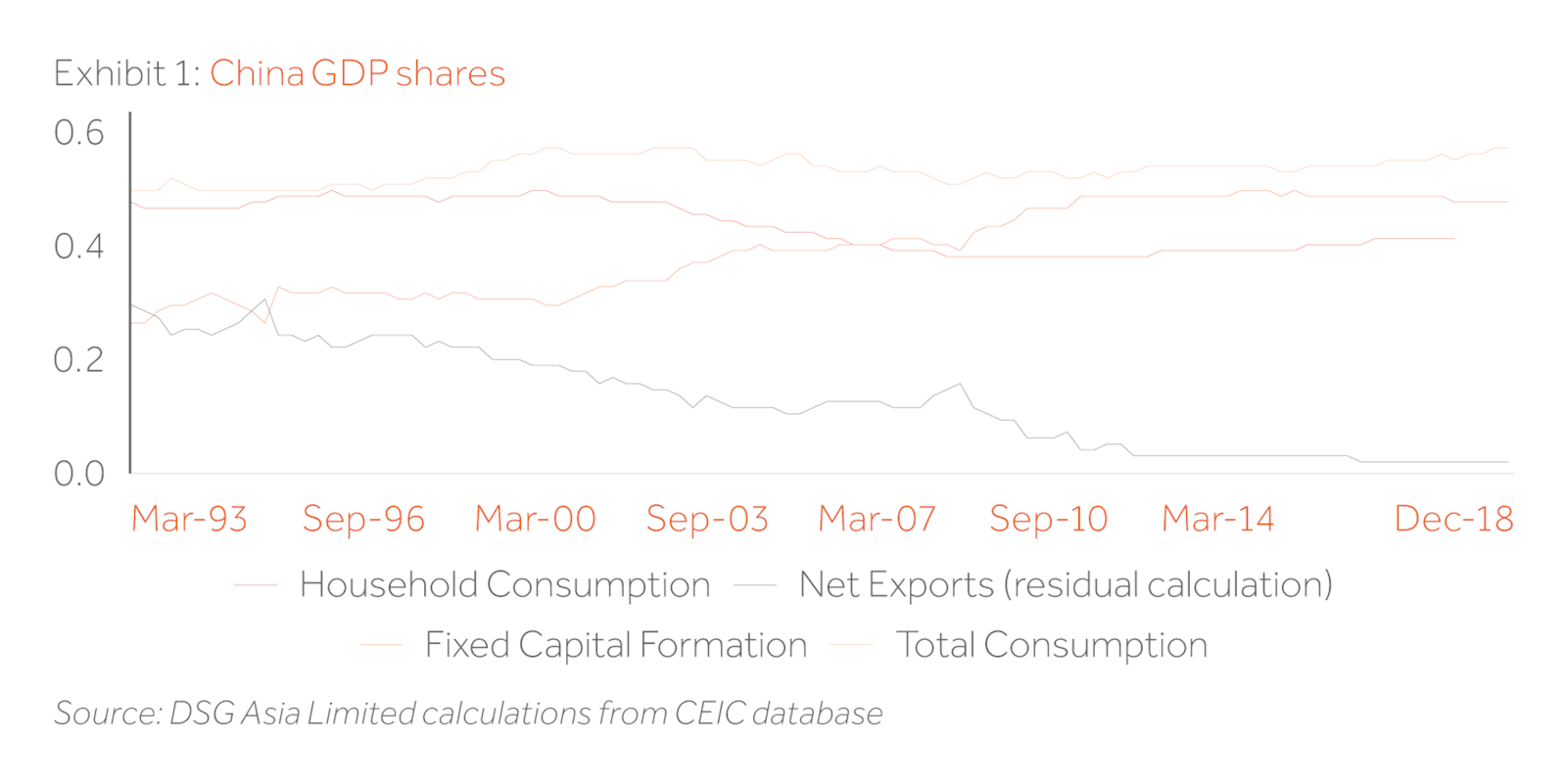

Prima facie, a much-reduced current account surplus in the decade following the Global Financial Crisis – from 9% of GDP in 2008 to only 0.4% last year – suggests that significant rebalancing has indeed been taking place. In reality, economic growth has remained significantly reliant on credit-fuelled investment. The household consumption share in GDP meanwhile has only edged up from 36% to a still rather low (by global standards) 39% of GDP.

Furthermore, in the context of President Xi’s desire to re-prioritise the leading role of the state sector, while the share of exports in GDP has fallen from 31% to only 18% over the last ten years, state companies now only account for 12% of total exports compared to 21% in 2008 and two-thirds in the mid-1990s. Conversely, foreign and Chinese private companies now comprise 42% and 46% of the total respectively. One might fairly assume that the ascendance of the non-state’s export share is a reflection of its superior efficiency and international competitiveness. Curtailed global trade and cross-border investment flows, and increased domestic resource allocation towards less efficient state entities, do not bode well for a productivity renaissance.

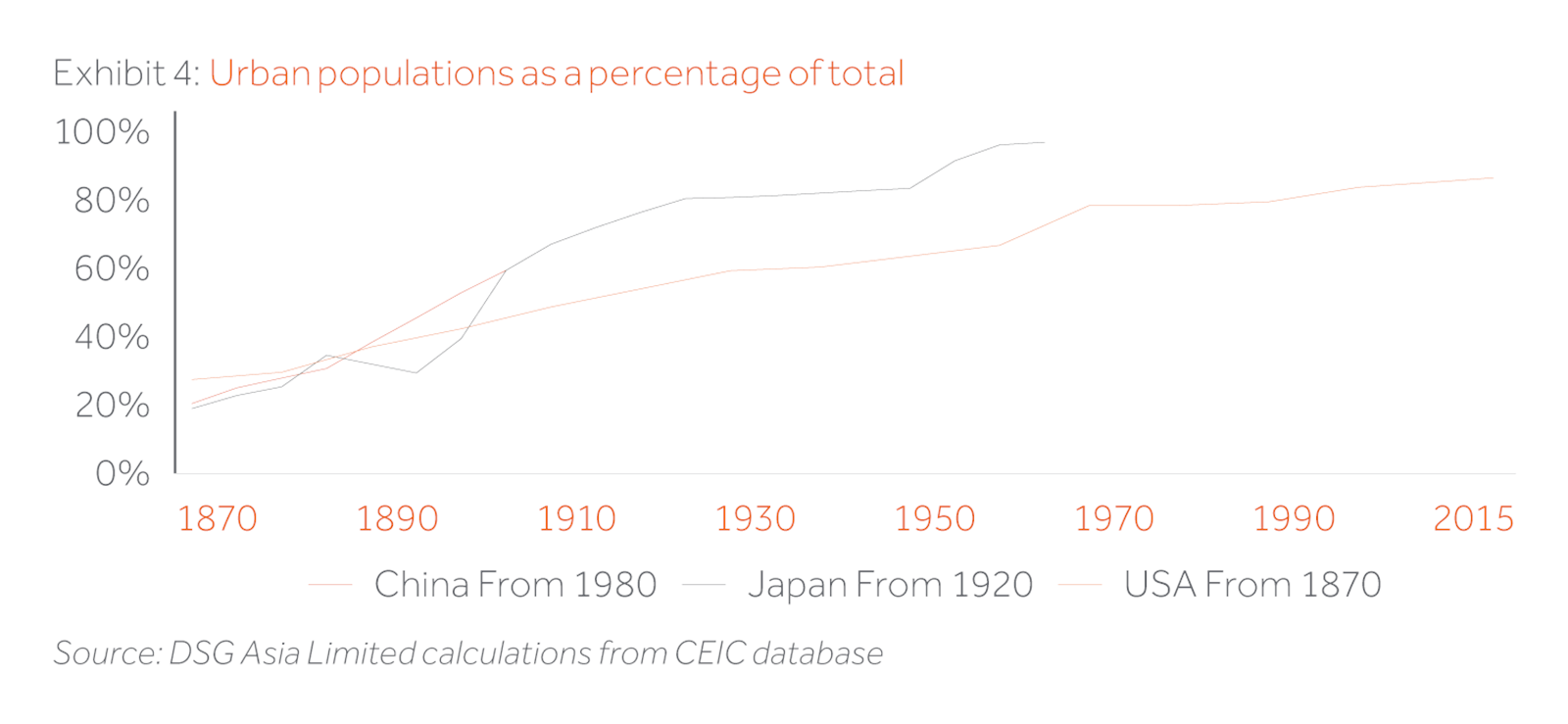

Nevertheless, China still has plenty of avenues for expenditure that could drive a resurgence in productivity and help propel the economy towards upper income status. For example, while the PRC has urbanised rapidly over the past four decades, based on the historic trajectories of the US and Japan, it still has significant potential to shift further masses from the countryside to the cities.

Furthermore, a fair proportion of those who have already moved to urban areas are currently housed in sub-standard housing and only have access to substandard social services. Ongoing building out of urban transport networks and slum redevelopment programmes, combined with deeper reforms to the household registration or hukou system, could unlock significant source of new growth potential. Of the 60% of the population deemed as urban residents, less than 40% have an official urban hukou.

There is no doubt that the range of macro challenges currently facing the Communist Party are daunting. Yet its past record over the past half century gives rise to cautious optimism that when push comes to shove, the Chinese leadership will pursue policies that further deepen and build on previous structural reforms. Xi Jinping has definitively made himself personally responsible for “The Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.” He now has to deliver.