On Sunday 28 July 2019, Egan Bernal, an unassuming 22 year old from the small town of Zipaquira, Colombia, achieved a highly improbable, others would say impossible, feat. He became the youngest winner of the Tour de France in the last 110 years, and the first ever South American to win the mythical cycling event. From incredibly humble beginnings – Egan trained on a hand-me-down steel framed bike in his early career – the young cyclist was shaped against consistent adversity in his youth, ultimately leading him to crown Col de l’Iseran, the highest paved mountain pass in the French Alps and the preeminent obstacle in the Tour.

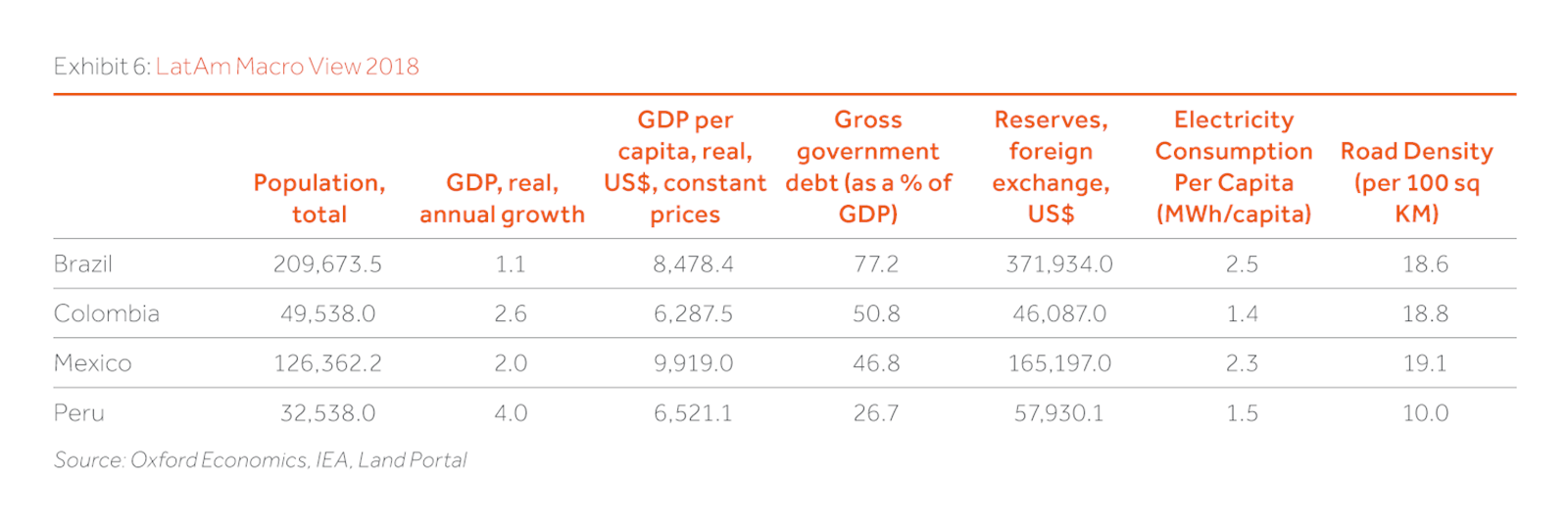

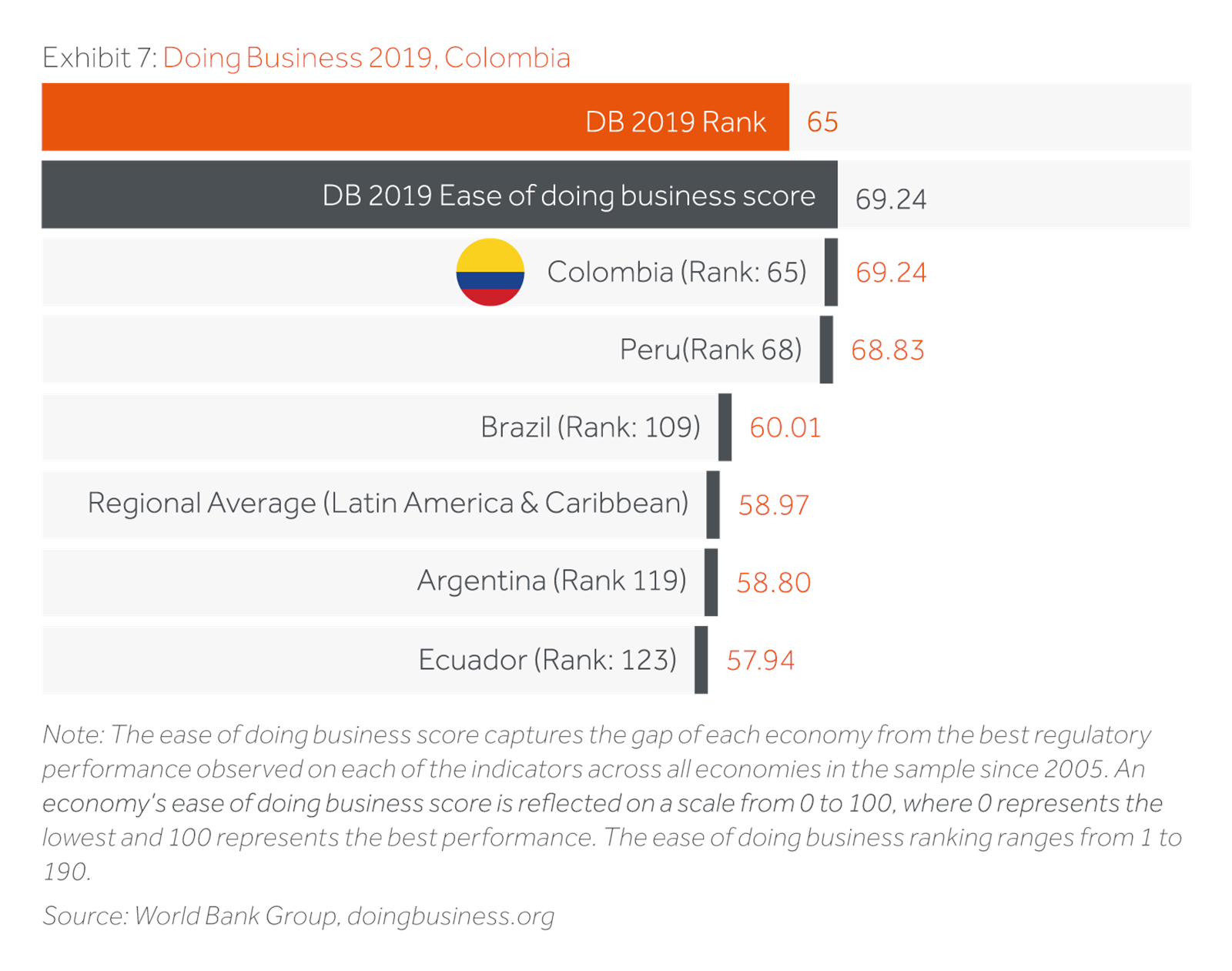

Colombia, the land of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s magical realism, is no stranger to improbable feats. With a population of 50 million and as Latin America’s fourth largest economy, Colombia is a core emerging market today. It has recently earned OECD status, following Chile and Mexico’s footsteps, and maintains an investment grade rating on the back of decades of orthodox macroeconomic policy and stable democratic rule. Colombia is the only Latin American country to have had no political coups in the last century and to have never defaulted on its debt. It has come a long way since its civil-war-torn past. Nearly two decades of consistent growth have more than halved poverty and made Colombians as prosperous as its more developed emerging market peers.

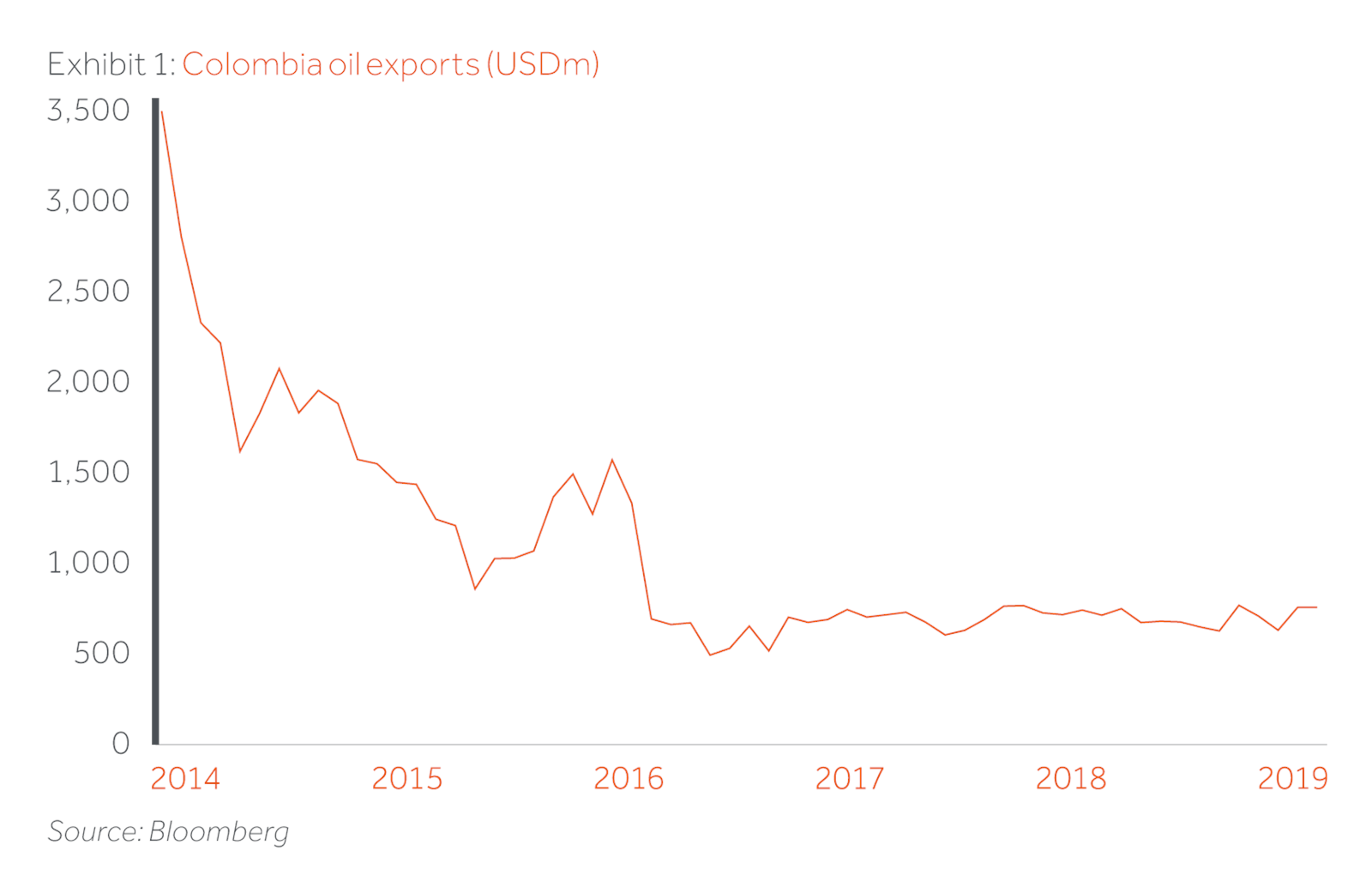

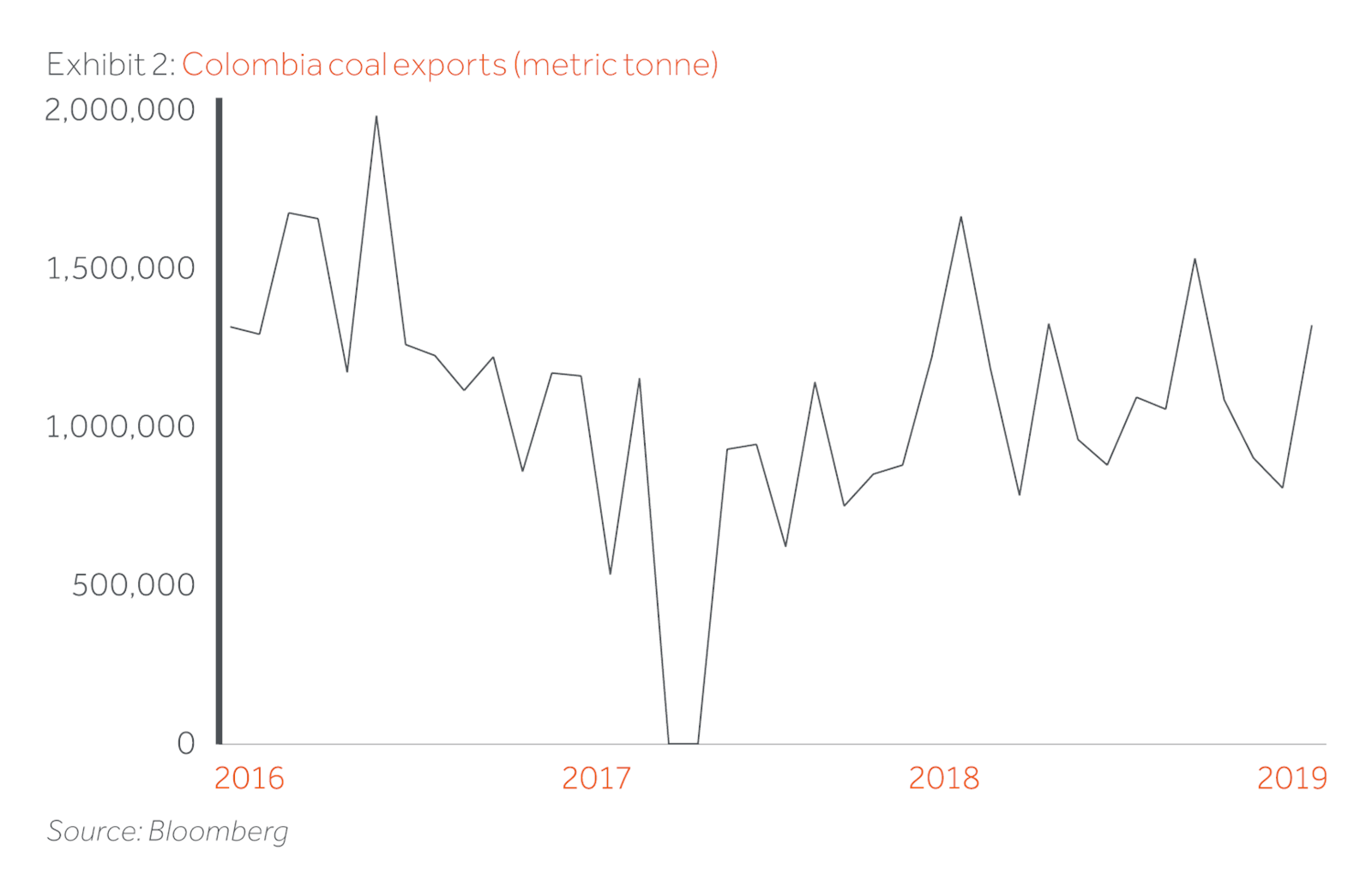

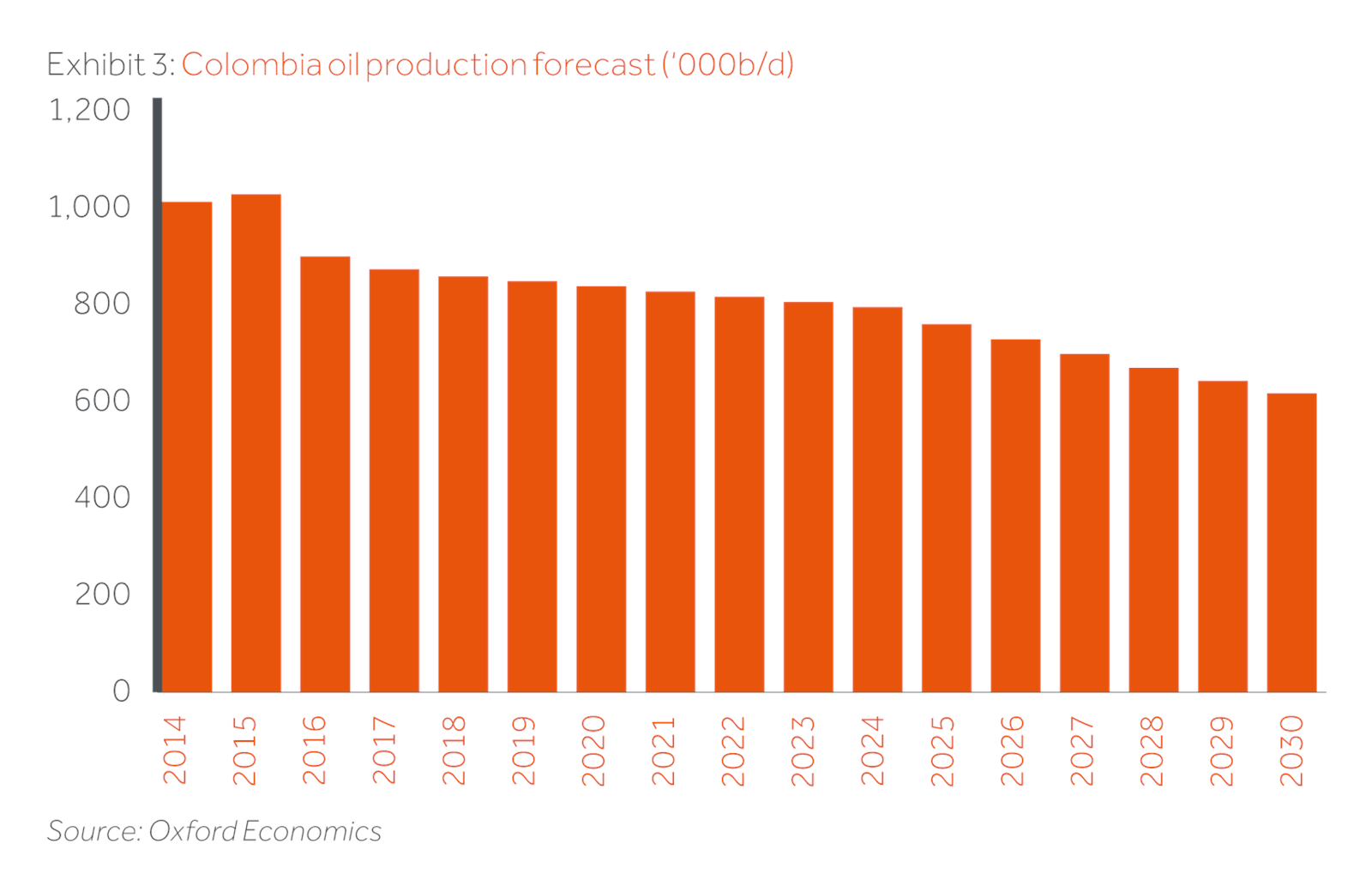

However, the country faces its own mountain pass. Three decades of oil discoveries and bountiful production, pioneered by Ecopetrol and subsequently by junior players, have made Colombia’s economy excessively reliant on the commodity. Over half of the country’s exports rely exclusively on oil and coal, two out-of-fashion products with an uncertain demand outlook. This has caused latent fiscal weakness, significant exchange rate volatility, recurring current account deficits, and increased foreign currency indebtedness, all held hostage by commodity price swings. All this amidst a forecast of dwindling domestic oil production, which could make Colombia a net importer by 2030. The country has one key mission; it must successfully diversify its economy away from oil and coal

The good news is that there are a series of identified policies and measures to achieve this and to battle the symptomatic weaknesses that oil-reliance has created. In particular, three actions are paramount: i) overcoming infrastructure bottlenecks that impede economic diversification, ii) implementing fiscal reform that provides solid ground to push forward a diversification agenda, and iii) proper implementation of a peace agreement to foster economic activity across the territory. The troubling news is that this requires significant political capital. One year into his term, Ivan Duque, Colombia’s young, centre-right, technocratic President, has lacked the political skill to implement this agenda. A protégé of former President and now Senator Alvaro Uribe, Duque has often fallen hostage to larger political forces at play, which have impeded swift action on these three fronts.

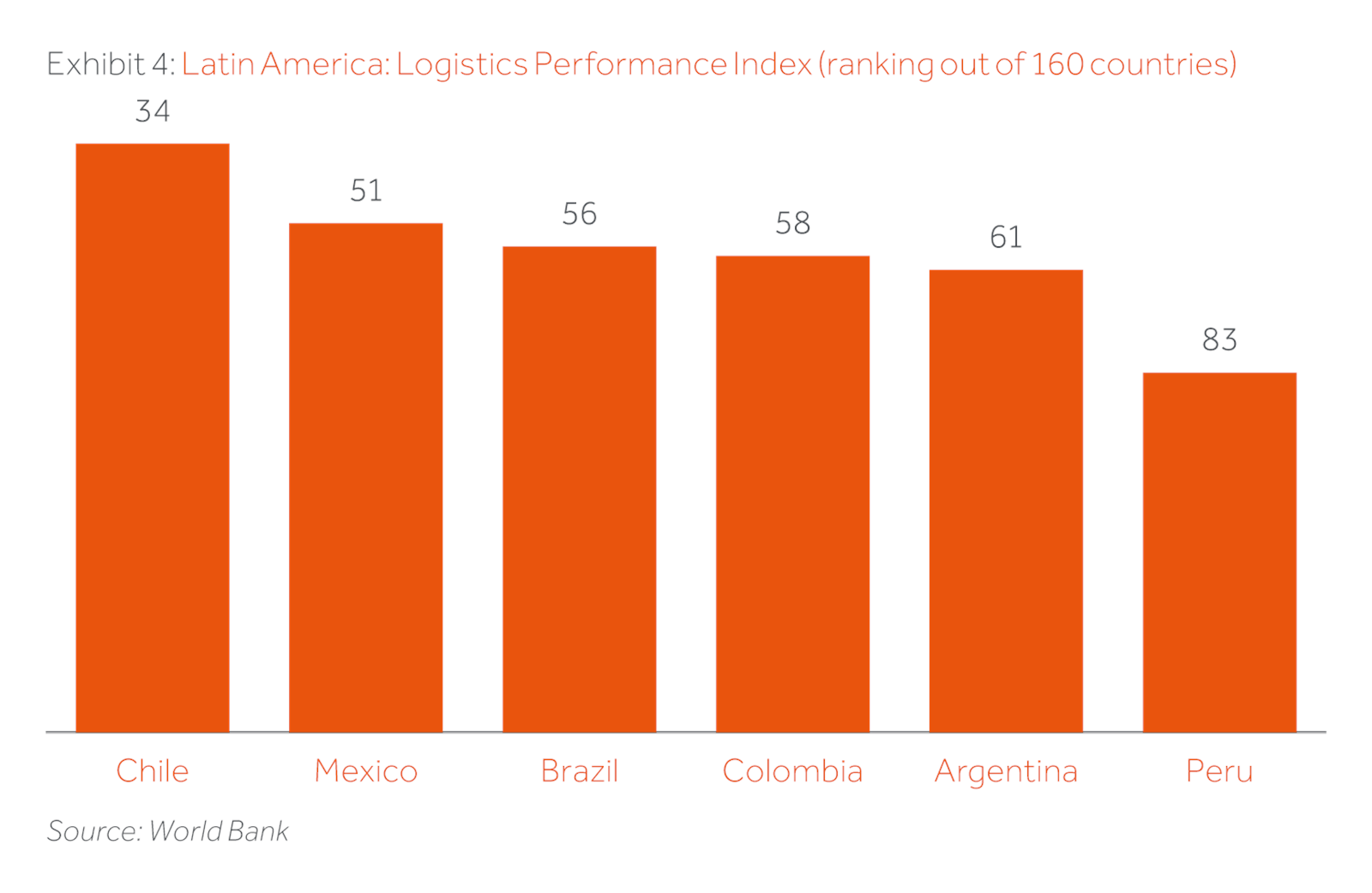

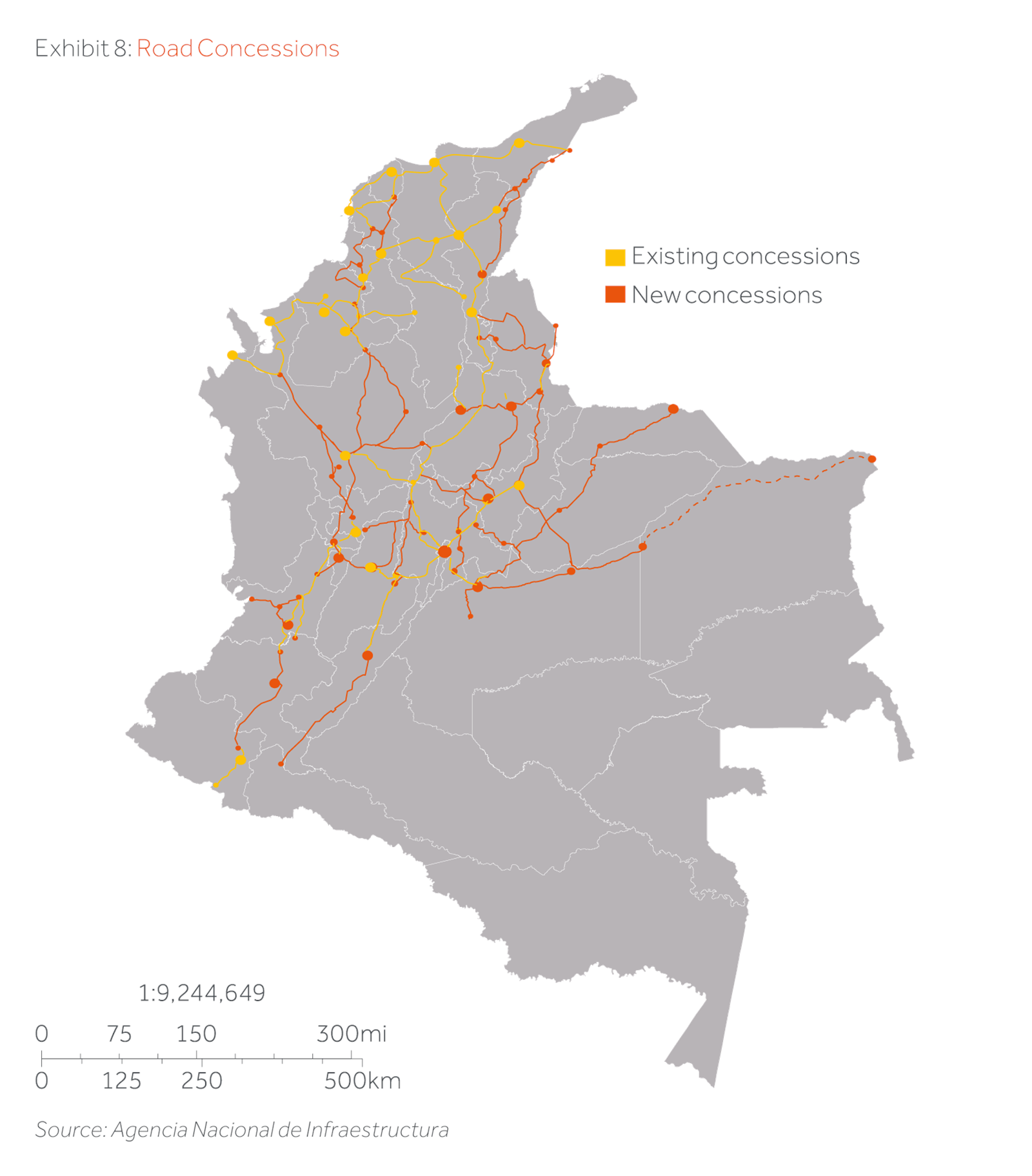

With a highly fragmented geography, it is not surprising that Colombia has significant transport infrastructure gaps. The Andes break into three separate mountain ranges in the country, creating a dramatic topography. The same mountains where Bernal trained also create severe logistical barriers for Colombian entrepreneurs to get their product across the country and overseas. As an example, an emblematic 90 km two-lane mountain pass ironically called “La Linea” (The Line) which connects the Pacific port of Buenaventura with the capital Bogota often takes 5-10 hours for truckers to cross. This has impeded cluster formation and economies of scale hindered the creation of new productive industries and raised costs for exporters. The country has the most to gain from transport infrastructure investment out of all its Latin American peers based on several studies. An emblematic road initiative called 4G, fostered by the prior president and launched in 2014, set out to tackle this challenge. Thirty projects came up for tender in total. Five years later the initiative has had some success but has also had challenges. Several projects were mired in the Odebrecht corruption scandal, and the contract and risk structures offered failed to attract broad foreign investor and lender participation resulting in construction delays. The administration needs to take note of this first round’s shortcomings to accelerate the creation of a robust transport infrastructure network.

Finally, diversification must stem from all corners of the country. In late 2016, the government signed a peace agreement with revolutionary armed forces FARC ending a 60-year conflict. There are multiple theories on what the much awaited “peace dividend” will bring for Colombia, with optimists stating it could increase structural long term GDP growth by as much as 30-50 bps. Meanwhile the short-term costs of implementation of the agreement are high, with over 70% of these borne by central government. Achieving a lasting peace will require thorough implementation of a peace accord, which in turn requires significant funding and political will.

Like Egan Bernal, Colombia and its President face their own versions of an upcoming Col de l’Iseran on the horizon. In its push to successfully diversify the economy and enable Colombia to continue on its solid trajectory, the country must relentlessly prioritise its policy objectives and leave aside less fruitful political bickering. Meanwhile, President Duque must learn quickly from his first year in office and garner the political support for his well-oriented policies. This might involve some key cabinet changes and a willingness to step down from his technocratic pedestal to engage with his political reality. Let’s hope that like Egan, he is sharpened by adversity too.