Do reserve losses, foreign exchange depreciation and recessions in Emerging Markets mean that investors should exclusively focus on developed markets for investments in a post-Covid-19 world?

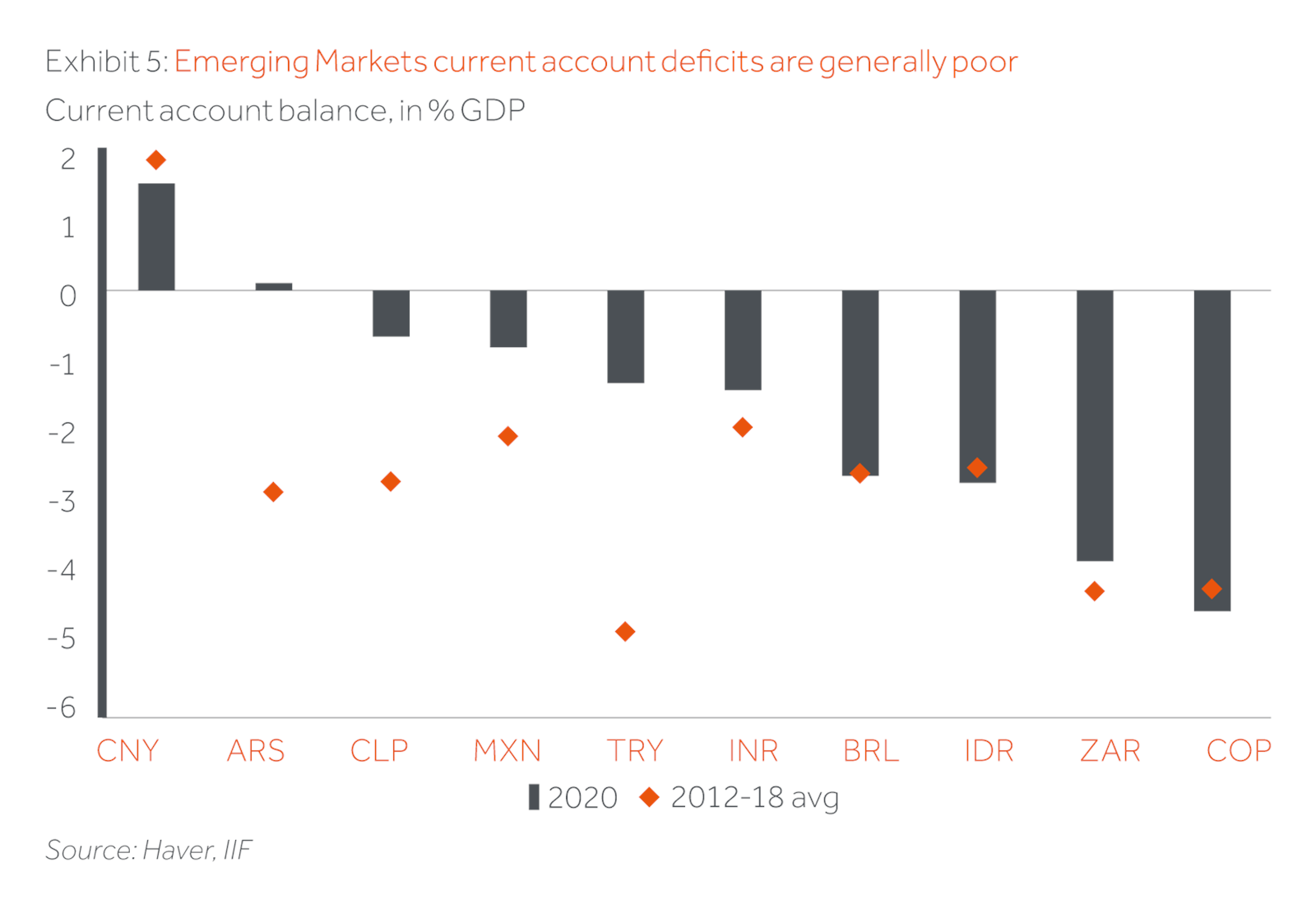

No one denies that Emerging Markets have their drawbacks. Very few of them run a current account surplus other than when in recession; even China is now in deficit, meaning that economic growth and financial stability largely depend on foreign capital inflows.

No one denies that the current crisis is enormous. Yet hold on before “emptying the baby out with the Covid-19 bath water”!

Twenty years back these flows were led by foreign direct investment, traditionally seen as stable capital with limited volatility.

Opening up of financial systems and more liberal foreign exchange regimes post the 1994-2001 Emerging Markets crisis mean that today, more than 80% of cross border flows to Emerging Markets come in the form of portfolio capital and migrant remittances.

In general in Emerging Markets, foreigners can own most of the debt in an Emerging Markets country. This makes the recipient country vulnerable to a sudden stop of capital flow.

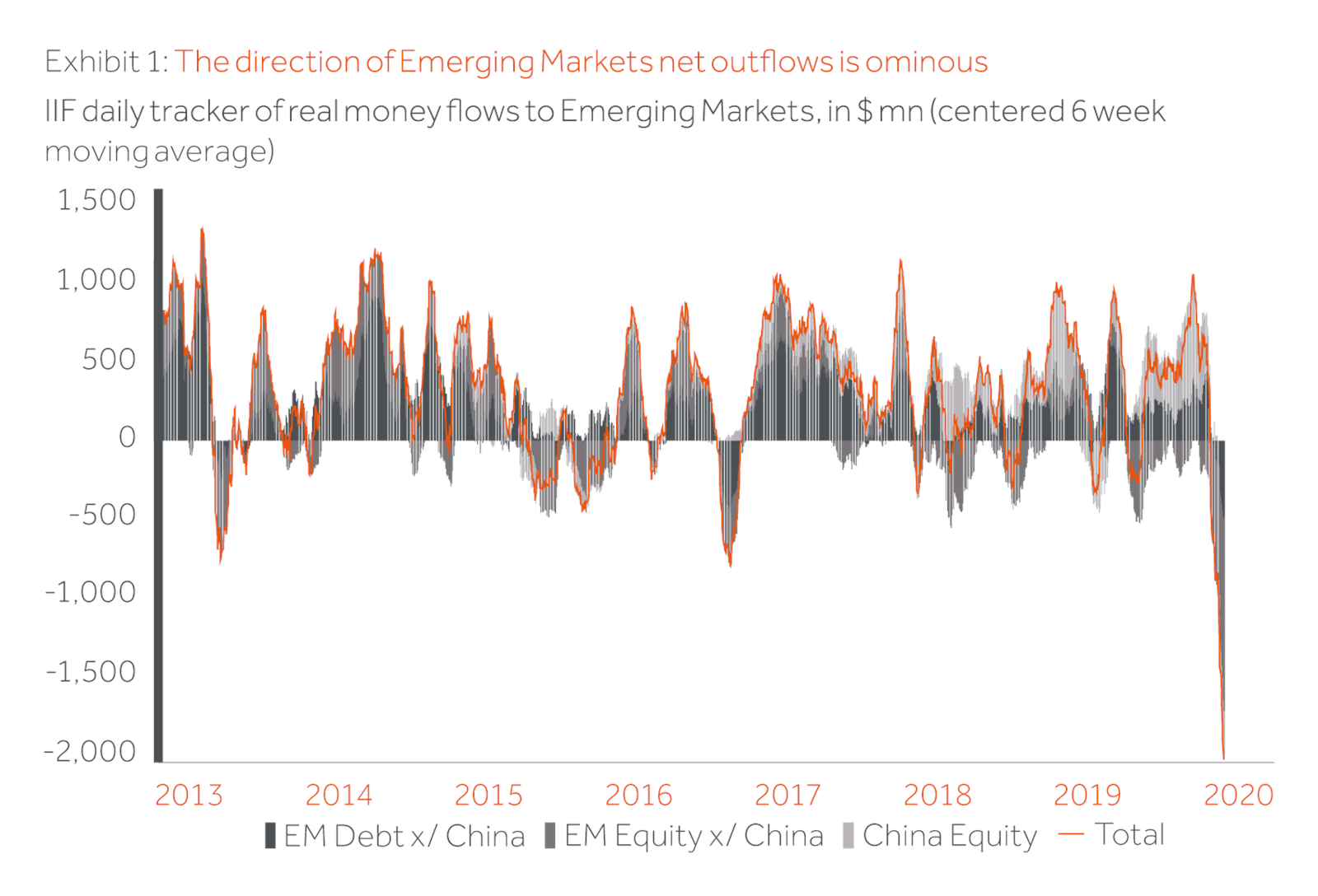

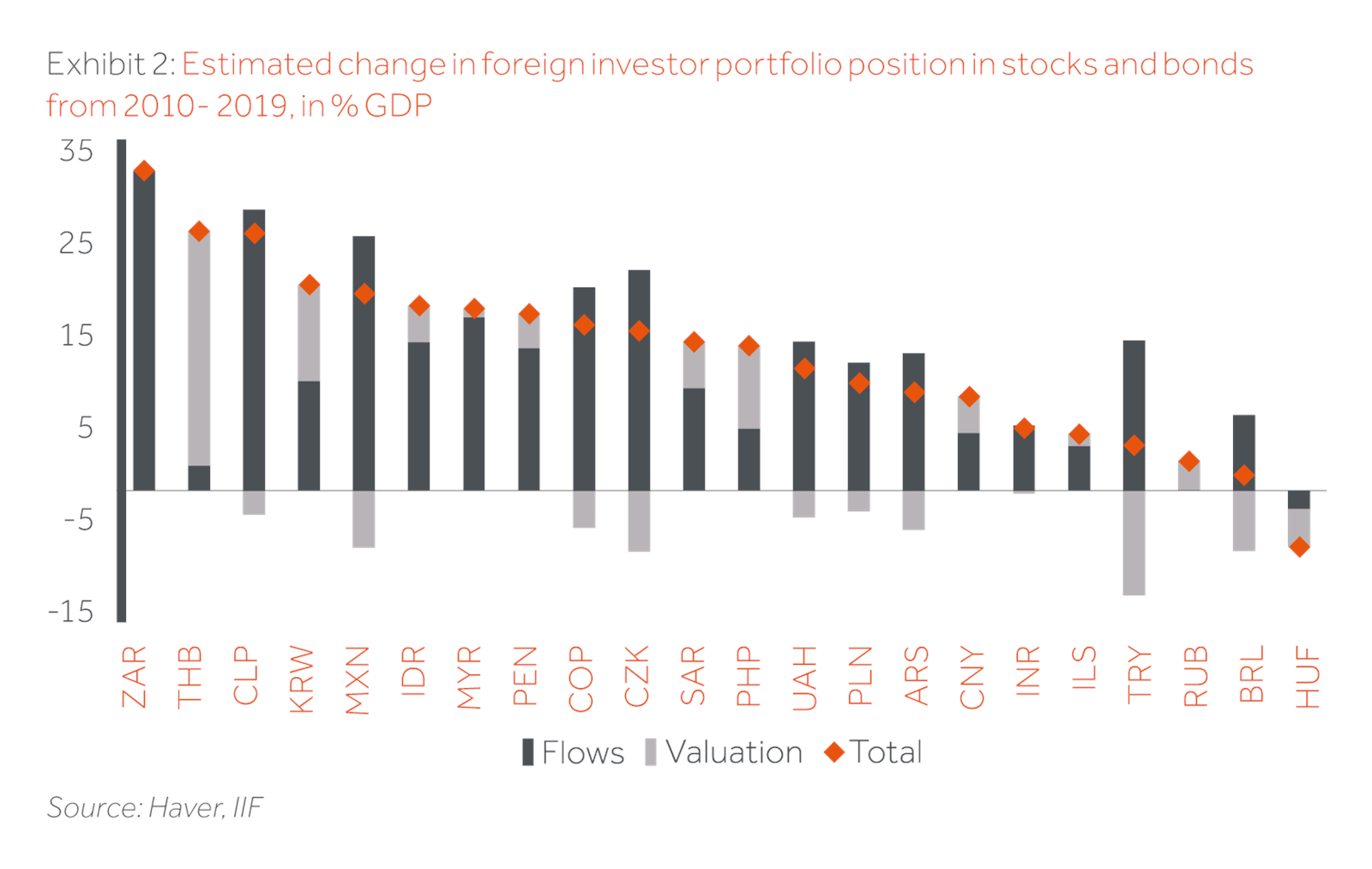

Estimated outflows in 2020 to mid-March from Emerging Markets countries are over $60 billion, an amount and pace which dwarves that of 2008 (Exhibits 1 and 2).

Prior to 2001 such flows saw destabilising currency dynamics under currency regimes fixed or pegged to the dollar.

Since then, FX reserves have been rebuilt and more flexible exchange rate systems introduced. Pegs do still exist, but the vast majority are in already dollarised countries, either trade based economies like Hong Kong or resource-based economies such as Saudi Arabia.

Hence, while currencies do plunge, the impact of capital flight on domestic banking systems is manageable, albeit painful, where fiscal deposits form a material portion of banking system liabilities.

Emerging Markets are not one size fits all, even though during sell offs it feels that way. We would broadly divide them into resource and non-resource driven economies.

Brazil, Chile and South Africa fall into the first group whilst China, Korea, India and Turkey are in the second. Some fall into both categories-Mexico for instance-but currency movements do seem to reflect the greater rebalancing risks of resource economies.

The single most important issue today in Emerging Markets is how that re‑balancing works. And the message is clear – recessions and currency declines have provided good risk-adjusted return opportunities for foreign investors.

There is no systematic relationship between immediately observed economic fundamentals and hard currency returns.

‘…Over the period 1900-2011 the quintile of countries with the hitherto weakest currencies produced materially better returns in dollars than countries with strong currencies…’

Dimson et al reported in Financial Times 2012

‘…History suggests that over the long-term exchange rate movements largely reflect-and cancel out-the impact of inflation. Exposure to exchange rate fluctuations should therefore not dissuade investors from holding Emerging Markets assets…’

Dimson, Marsh and Staunton Credit Suisse Investment Returns Year Book 2019

We have all heard the claim that Emerging Markets investing is first, second and third an FX decision. But one must pay attention to past lessons to benefit from future opportunities.

This reflects valuation arguments (e.g. UK asset valuations after Brexit) and the position in the monetary cycle where weak currency drives tightened domestic monetary conditions, putting downward pressure on local currency asset values.

Heavily sold currencies and depressed domestic economies allow two “bites of the cherry” for foreign investors.

The best major Emerging Markets stock market over the period 1993-2018 was Brazil at 11% pa, yet China returns were only middling at 5.1% over the same period despite superior growth and lower inflation. A one-dimensional strategy driven around GDP growth and sound investment decision making make for sub-optimal performance.

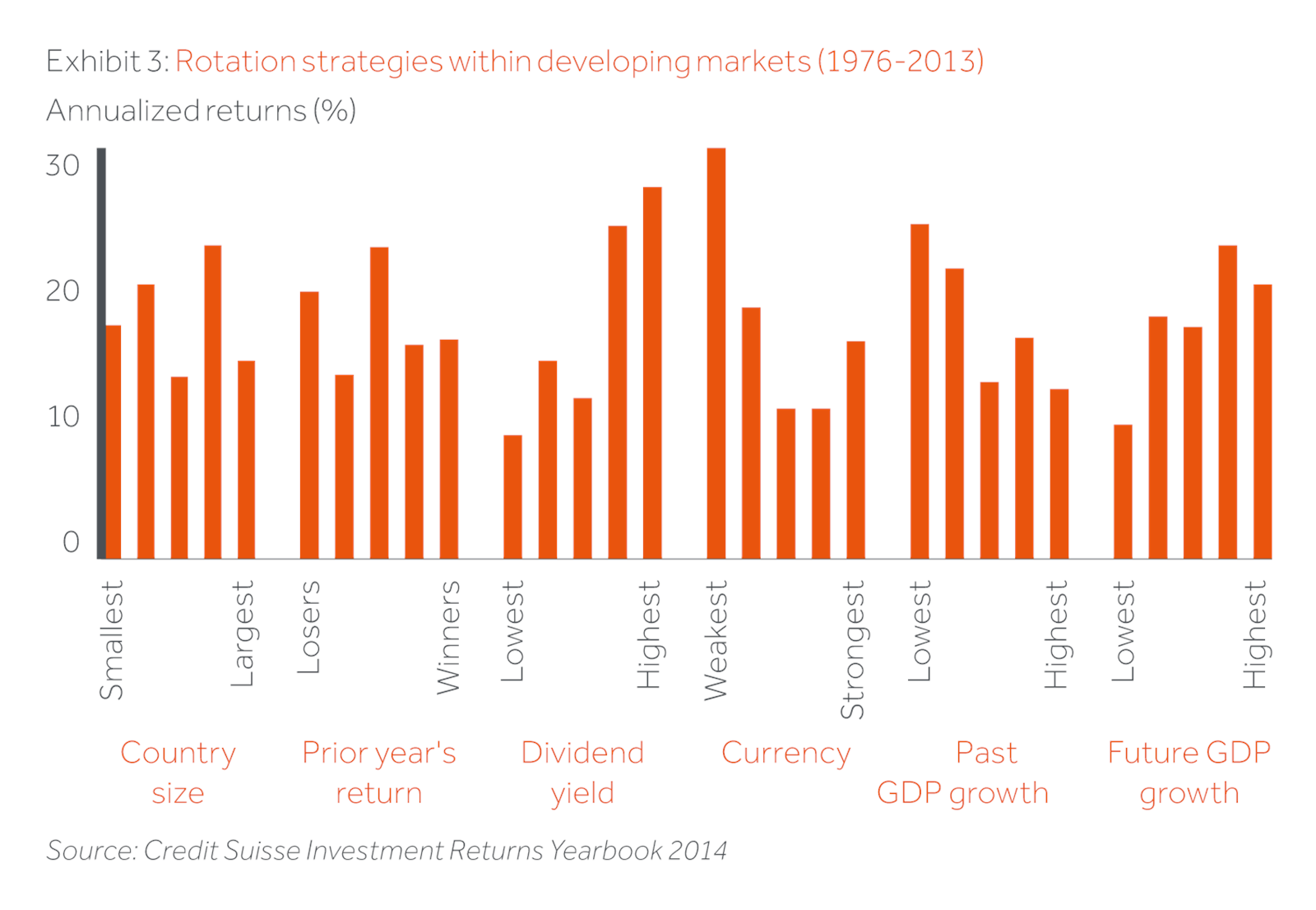

The above 2014 analysis from Dimson et al (Exhibit 3) in fact shows no connection between currency and subsequent returns, indeed it suggests that the best returns come after a currency drawdown and a growth slowdown. This sine qua non is intuitive since a weak currency is accompanied by a reversal in flows, followed by tighter domestic monetary conditions.

So in a post Covid-19 world, all assets must be cheap…right?

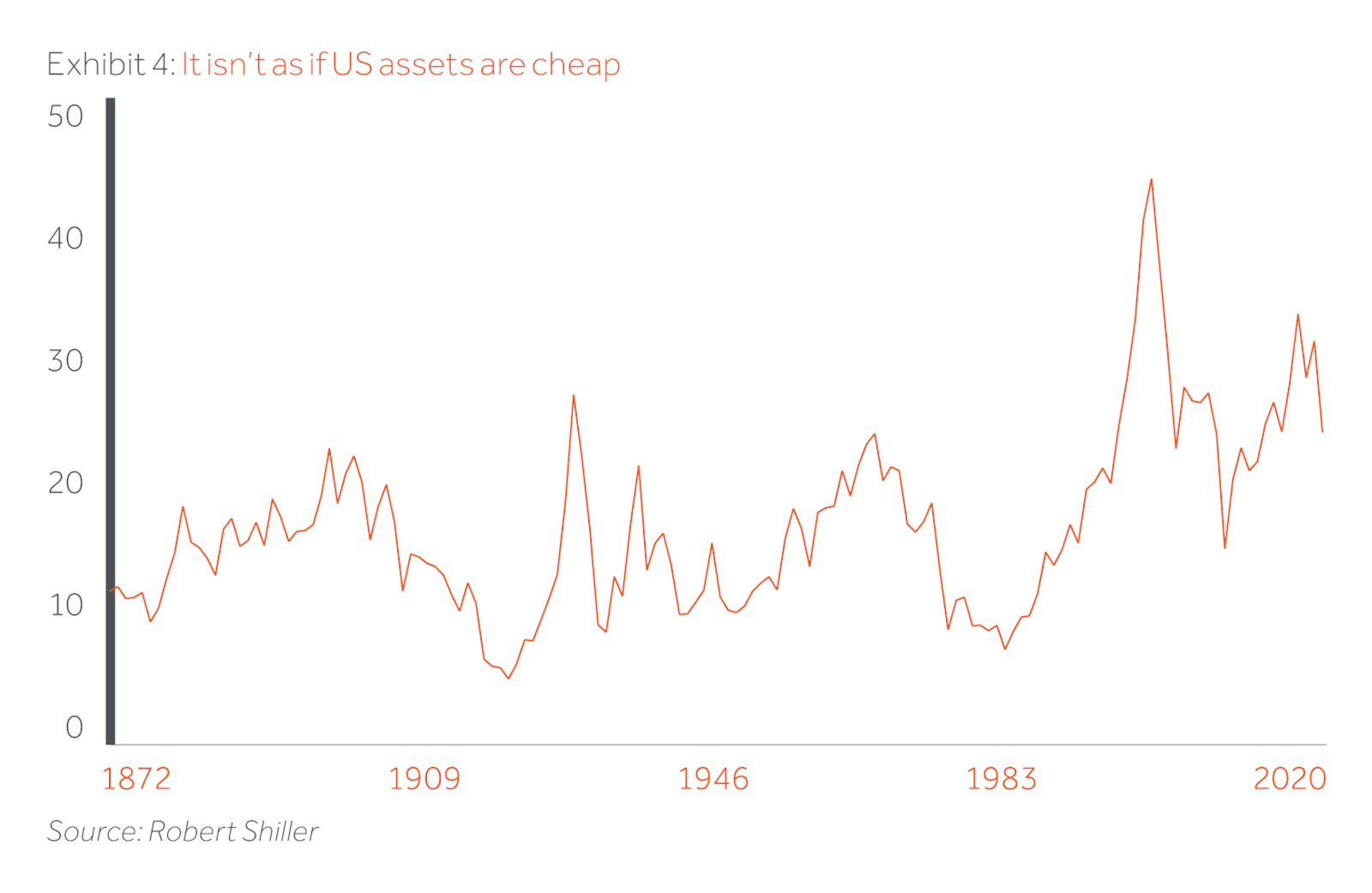

The long term value of US equities has declined from the level shown in Exhibit 4 on this page, as have interest rates. If we assumed that there was a 20% drop in the Shiller Price-to-Equity metric, then it is currently around 30 times, which is hardly cheap by historic standards.

Where “cheapness” exists in areas such as high yield or corporate debt or sub-sets of equities, it is accompanied by equally perilous cash flow dynamics in particular sectors like oil and gas, hospitality, transport and so on.

By contrast, Emerging Markets equities are now selling at or below book value. There are clearly vulnerabilities in Emerging Markets, particularly those where natural resources are a fiscal bedrock.

Some countries – notably India – and Korea which are net importers of oil will benefit from materially lower oil prices. Equally, foreign investors dominate many Emerging Markets bond markets making amortisation and roll over uncertain in the near to medium term.

The immediate sudden stop in world activity hampers trade so an Emerging Markets export or services led recovery on trade accounts is unlikely.

Emerging Markets economies will not escape a brutal and rapid adjustment

Faced with these realities, two things are happening in Emerging Markets. Firstly, domestic demand is contracting sharply and secondly, currencies are falling because of outflows.

Recessions across Emerging Markets are likely to ensue, further reducing fiscal take because indirect taxes in general are far more important than income-based tax given levels of per capita income. Exhibit 5 suggests there is little fiscal room to move for Emerging Markets governments.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that 2020 will be a challenging moment for Emerging Markets’ economies. Not only is growth under threat, but fiscal dynamics will be challenged by lower tax collections and in some cases reducing natural resource rents.

Some governments are going to face a protracted struggle to recover the gap generated by big fiscal deficits largely or partly financed by non-domestic flows.

But there will likely be a wide open Emerging Markets “door”

It is likely that governments will fall back on privatisation to bridge fiscal holes. In an environment of tight domestic monetary conditions and reduced cross border flows, the buyers of these assets have considerable advantage.

Equally as the private sector becomes stressed by weak domestic demand, the private sector will be more open to foreign purchase of key assets. This was the case in Mexico post the 1994 peso devaluation, Asia after 1997-8, and Emerging Markets in general after 2008.

Weak currencies and economies have provided excellent subsequent returns for foreign investors. General economic conditions and fiscal balances are more volatile as an offset, so that in turn will require a lower price entry point to justify reward for risk.

Some of this is already in the (Emerging Markets) price

Our argument based on historical evidence is that the best returns start from undervalued currencies and asset prices. We can see from listed equities that Emerging Markets assets are cheaper than those of the US. How about currencies?

Actis generates a fair value model for major Emerging Markets currencies relative to the US dollar. The model looks at relative inflation differences in estimation of fair value. The concept of fair value can be elusive; you don’t know that you are there until after you arrive, which means that only material deviations from trend are worth noting.

That said, the movements in 2020 are dramatic. In the initial stages of the Covid-19 collapse, resource heavy currencies such as the Mexican peso and South African rand were particularly weak as were those with fragile funding backdrops such as the Brazilian real and Turkish lira.

More recently, wholesale deleveraging has also hurt currencies that benefit from lower oil prices such as the Indian rupee. Bearing in mind that Covid-19 is a deeply deflationary process, the vast majority of major Emerging Markets currencies are well below fair value and some face immediate devaluation pressures over and above the substantive depreciation to date (e.g. Nigerian naira).

Domestic recession, reduced trade with China and lower oil prices are creating a shortage of US dollars. The US trade deficit is almost entirely trade with China plus energy imports. A lower deficit means that fewer dollars are printed to finance these imports and leaves the rest of the world short of dollars.

This will not last forever. Oil below $40/bbl hits the US shale industry hard: cash flow break even levels are typically in the $40/bbl plus range. Overseas receipts on the net international investment position also shrink as a result of a strong receiving currency. US exports will continue to be hampered by supply chain issues, even if these are only medium term. And finally, the major expansion of fiscal and monetary reserves through “pumped-up” QE and Fed swap lines supplies “unlimited” dollars to buyers.

The dominant risk to currency values is if the citizens of that country lose faith in the currency as a store of value. Under this circumstance – as Argentina, Venezuela and Zimbabwe have learnt so painfully – there is little way back.

A swing from current account deficit to surplus reduces pressure on the exchange rate as demand for FX falls. Strong FX reserves and a credible financial regime help this trend.

Countries with strong domestic savings movements “mop-up” cheap local assets as foreigners sell out. The key though is that domestic holders of the currency do feel that the currency is a legitimate store of value, and low inflation rates help a lot in keeping this faith.

Material deviations from the trend – either up or down – are threat or opportunity. Today – albeit with risk caveats – the balance is tipping towards opportunity.

Financial conditions matter

Lower currencies tighten domestic financial conditions. FX reserves tend to be utilised to roll over shorter term foreign currency liabilities.

In turn the adjustment of trade accounts through plunging imports is particularly painful for resource economies and less so for trade-based countries. In time this is reflected in a trade off between asset pricing and volatility of financial conditions.

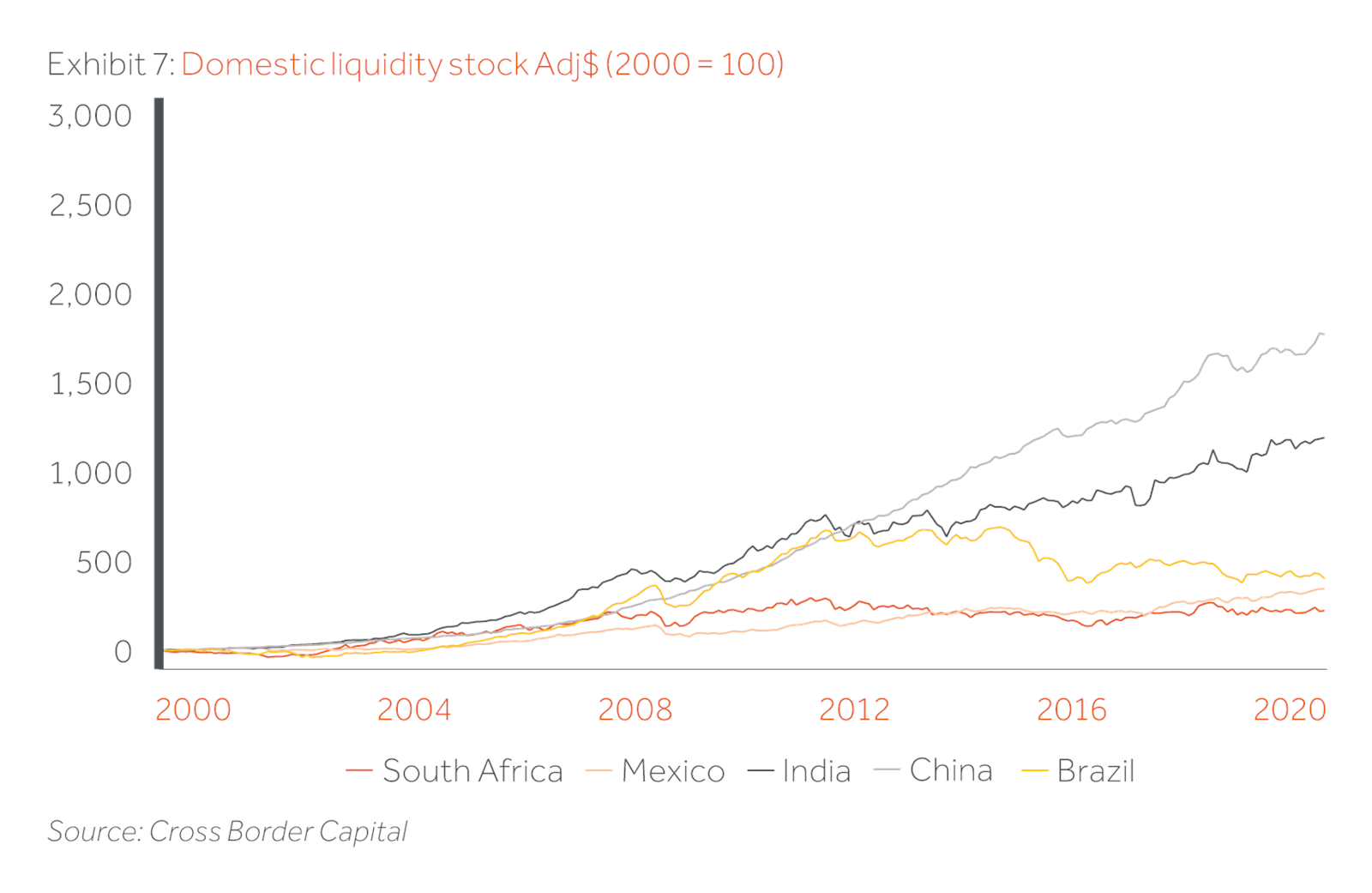

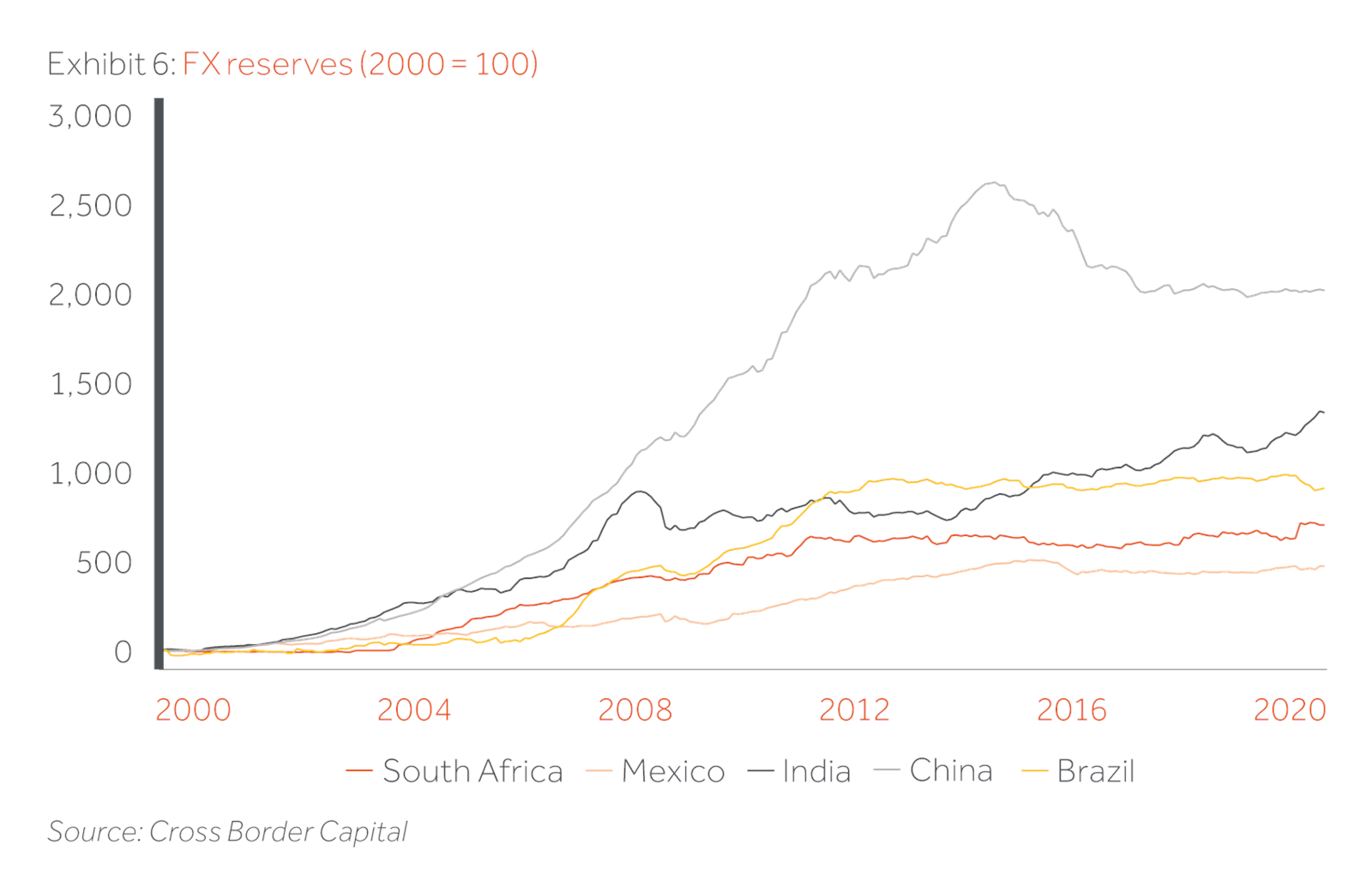

One piece of good news – for some of the larger Emerging Markets countries they enter the crisis period with strong foreign exchange reserves which allow them to sell FX and buy domestic currency thereby sustaining domestic liquidity for some time (see Exhibits 6 and 7). (FX reserves are of course simply a part of the balance sheet of the central bank which can use them to increase or decrease supply of local currency).

Equally this crisis begins with adequate stocks of domestic liquidity. These will be drawn down quickly as capital flows out. Better though to start in a healthy than a perilous position.

One worry-will countries introduce capital controls to try and trap foreign assets inside the country? This was attempted in 1997 by Malaysia and Slovenia. At the time the International Monetary Fund (IMF) frowned on these moves but in recent times the IMF seems to be mulling over the idea again.

We doubt that this will happen other than in circumstances of extreme distress; for instance Turkey resisted this tactic in the devaluation crisis of 2018-19, reasoning that at a time when they needed to roll over debt and attract new capital, gating flows was hardly sensible. Our sense is that need makes countries more open to new flows-certainly this is the anecdotal evidence from China in recent months.

So what of future Emerging Markets asset demand?

Global savings rates have been severely impacted by Covid-19 and globalisation has taken a huge blow. Savings schemes which discount future liabilities using bond proxies will see a material fall in funding ratios. ‘Future-generation’ funds sponsored by governments will have experienced significant reductions in value if backed by natural resource-based cash flows, further hampering fiscal bail outs of the sort seen after the Arab Spring.

Leverage is proving to be a distinct negative and it is easy to conclude that US leveraged finance with little or no covenant backing is going to suffer a severe hit on asset values.

In this circumstance, the demand for long duration, stable cash flows closely linked to social stability will likely be material. This translates into demand for electrification and social infrastructure and these asset types will be at the top of a limited list of spending priorities. Buyers with dry powder will be in excellent positions. An absence of structured finance and applied leverage is an advantage as assets come with limited liabilities attached.

Covid-19 is ravaging economies and savings as I write. Asset owners will struggle for a long time to recover lost ground. Taking the safe option is understandable whilst the tempest rages. “Getting back to land” as it abates takes skill and entails taking calculated risks.

Happily, experience points the way to stable cash flows at low prices without excessive liabilities attached. Many of these will or should exist in the countries which make up 80% of world population and resources – that is the Emerging Markets.

A personal note

The author has been investing in Emerging Markets and analysing them for over 30 years. He saw the “sugar rush” of the 1993 bull market being derailed by rising interest rates and tighter liquidity the following year.

As a portfolio manager he recalls the gut wrenching shock of Mexico devaluing on December 20th 1994 which set off the rolling Emerging Markets crisis of the next 7 years.

Along the way, he learned that funding dynamics set prices more than a single issue. He watched on television as a major holding in Indonesia was “burnt to the ground” in 1998. He learnt over this period that recession and weak currency provided great opportunity and as a global asset allocator and director of investment strategy applied these lessons effectively in 2008-09. This time…