As 2020 began, sentiment had been boosted, at least temporarily, by a time-out in the US-China trade war.

Unfortunately, Beijing’s initial cover-up of the outbreak, notwithstanding its brutally effective second round response, has served to further fuel burgeoning anti-Chinese sentiment. Tensions have always been about much more than just trade and were never going to be solved fundamentally by China agreeing to buy a few more American agricultural products, nor indeed its more recent provision of medical equipment to other stricken countries.

Nevertheless, rather than acting as a spur for renewed global cooperation, the virus has morphed into an unedifying secondary outbreak of finger-pointing and trade in conspiracy theories.

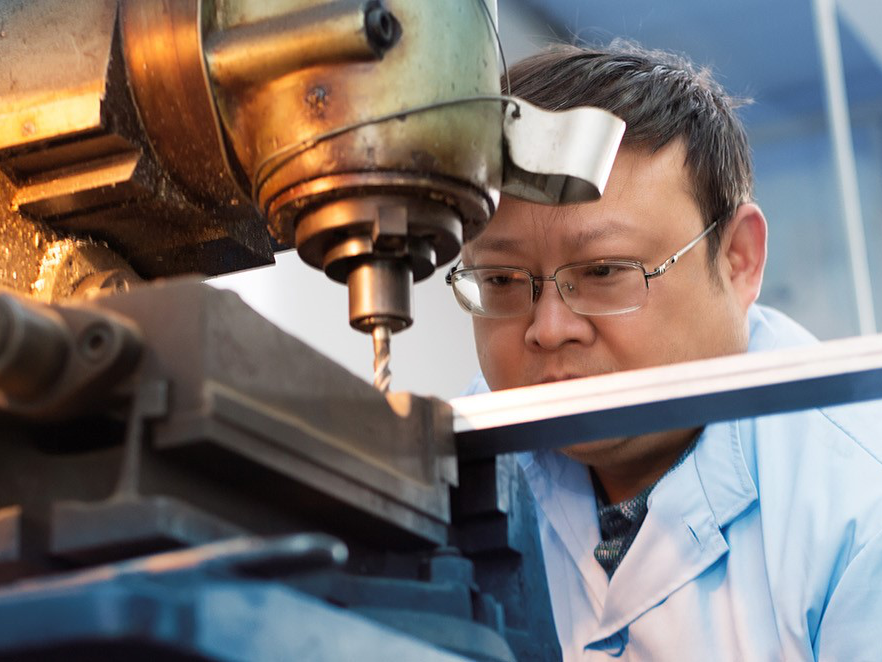

North Asia, employing an eclectic range of responses, albeit with certain communalities, appears to have had reasonable success in “flattening the curve”. In recent weeks I have been conducting regular channel checks with various corporate and personal contacts across China and the region which indicate that labour supply and productive potential are steadily recovering. The emergent corporate fear though is that there will be no customers to buy their wares even if they can start to produce again as normal.

Specific to China, many private sector contacts – foreign and local – report that Communist Party officials have been dialling back the hostility to non-state enterprise which has characterised the Xi Jinping years. However, few seem willing to bet that such attitude changes are anything more than a near-term expedient.

Hence, they are preparing for a world where separate entities are required to conduct business in domestic China and in other regional blocs. This will add to corporate costs in terms of system duplication and the requirement to hold higher inventories sourced from diversified supply locations. But few seem willing to abandon the lure of Chinese internal demand altogether.

As I have discussed in previous editions of The Street View, much of Asia is well positioned to benefit from such realignments assuming it can remain relatively politically neutral and can enhance its absorptive capacity.

Not all production can or will relocate from China but even small shifts away from the PRC represent large numbers in the context of its smaller neighbours. A welcoming investment climate, flexible labour markets and improved infrastructure should all help to attract renewed FDI flows.

Or so goes the theory. But how are relocations of production and disbursements of new investment playing out on the ground? Again, I have been meeting with companies and industry bodies, and, before the virus’ onset, had been travelling extensively across the region, to fathom where more short term trade flows, and longer term capital investments, were being diverted.

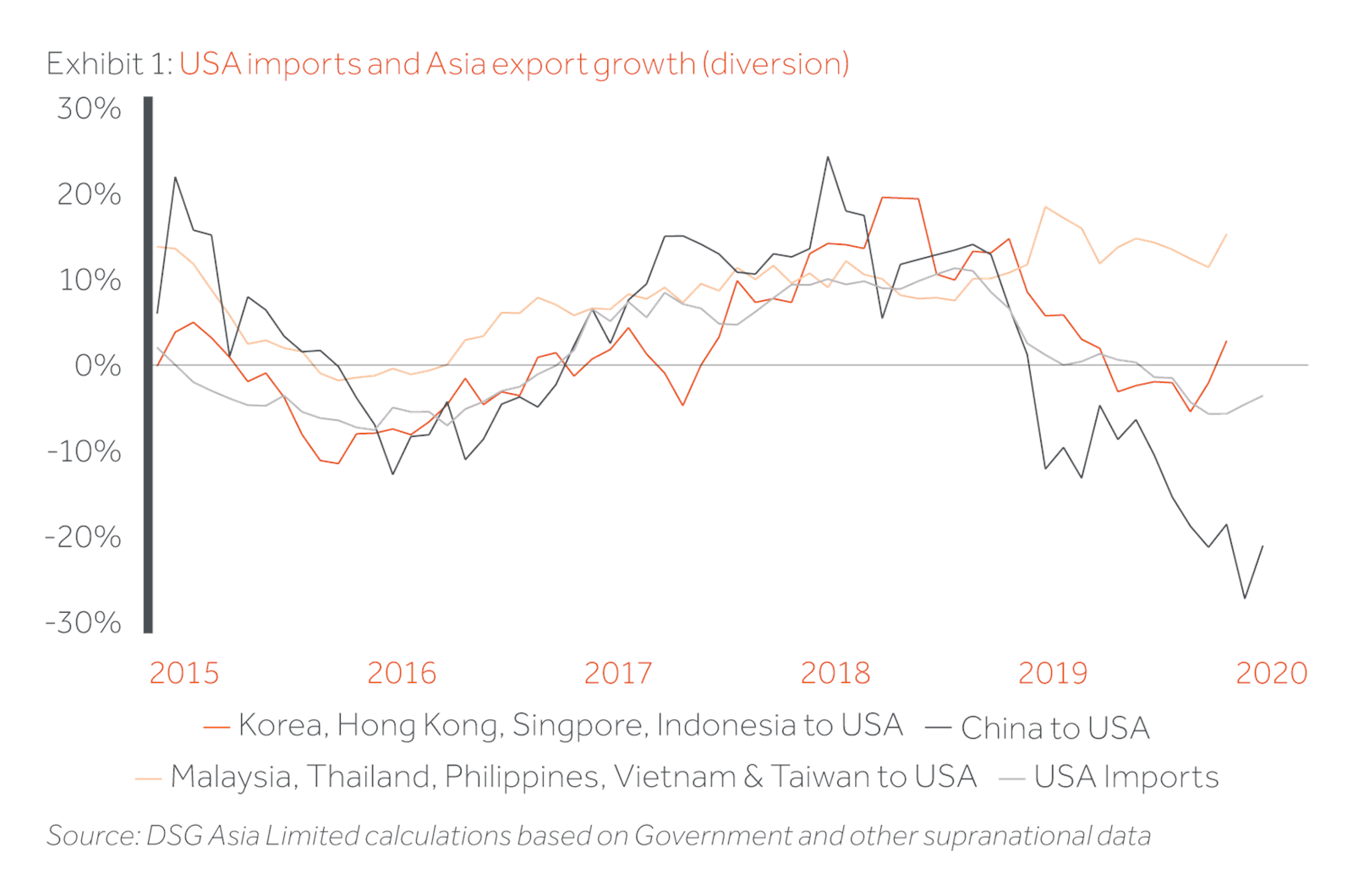

Obviously, it is easier to rapidly rebook shipments and crank-up or dial-back production in different locations to circumvent tariffs, than it is to install and to begin operating out of greenfield capacity.

The export diversion chart (Exhibit 1) shows clearly the near-term winners and losers. I should caution that overall export growth has remained pretty soggy across the board but if we just consider shipments to tariff-distorted USA, the major immediate beneficiaries have largely been in ASEAN with the notable exceptions of Indonesia (not participating) and Taiwan (doing very nicely, thank you).

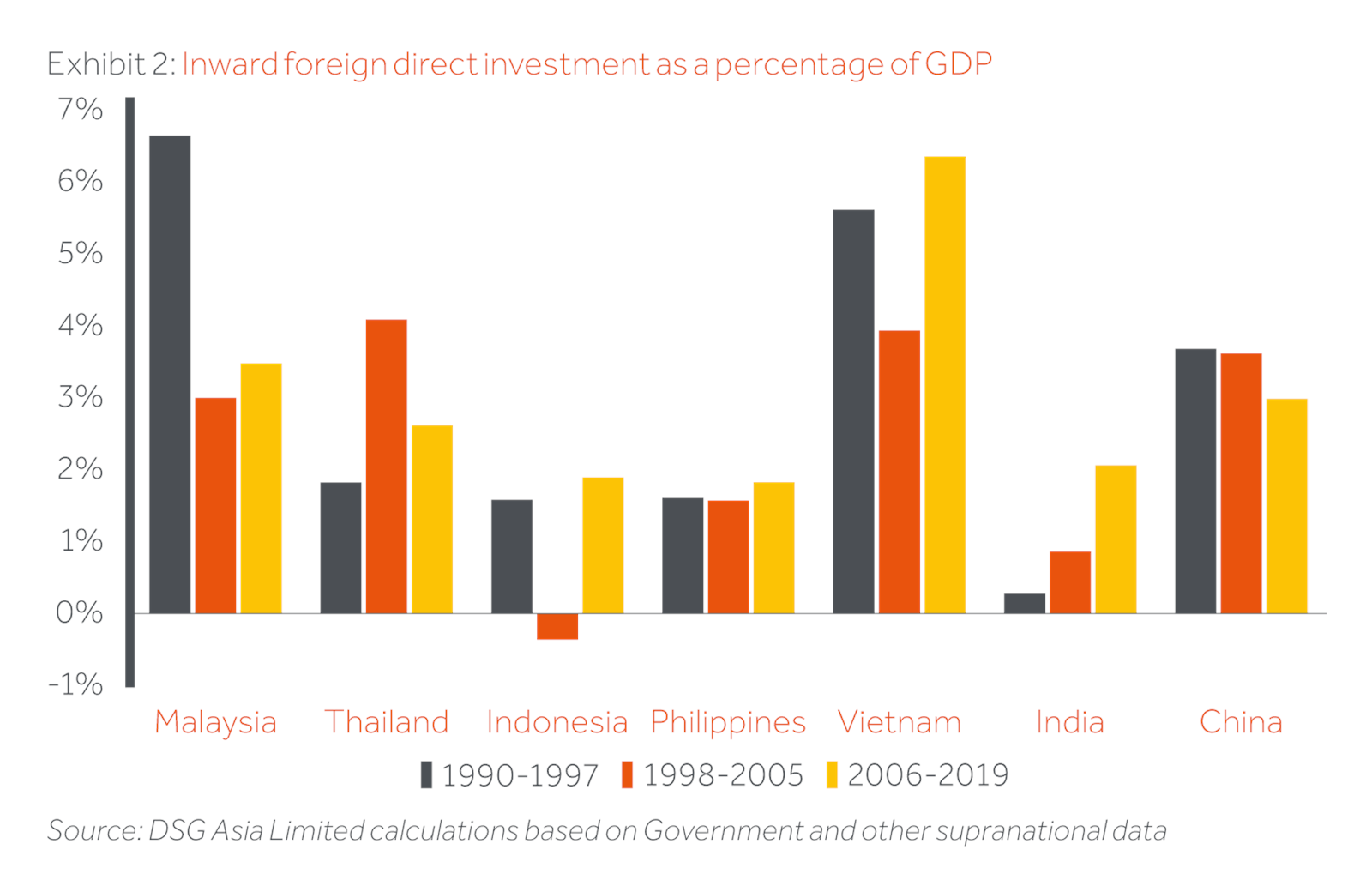

Vietnam has been the FDI darling of the region in recent years (Exhibit 2) while Thailand, Malaysia and, to a lesser extent, the Philippines, have plenty of installed capacity, that had been operating well below maximum utilisation rates for a number of years, which could subsequently be dialled-up again relatively quickly.

Indonesia, with its restrictive labour laws and nationalist, protectionist mindset, is the notable ASEAN outlier. The passage or otherwise of President Jokowi’s recently-submitted Omnibus Bill through the Legislature will be a crucial development to monitor.

As for higher cost North-Asia, Taiwan has been similarly a trade diversion winner albeit more in terms of capital-intensive, higher value-added production. Japan has also seen a modest uptick in its US shipments but Korea, for reasons both external and self-inflicted has failed to participate.

The more immediate evidence from FDI flows is rather less conclusive. For starters, installing new capacity is hardly an overnight process. Moreover, the fluid nature of the trade dispute makes long-term planning rather challenging.

Accordingly, if a company has capacity in alternative locations not being fully utilised, longer-term, new investment decisions may tend to be postponed.

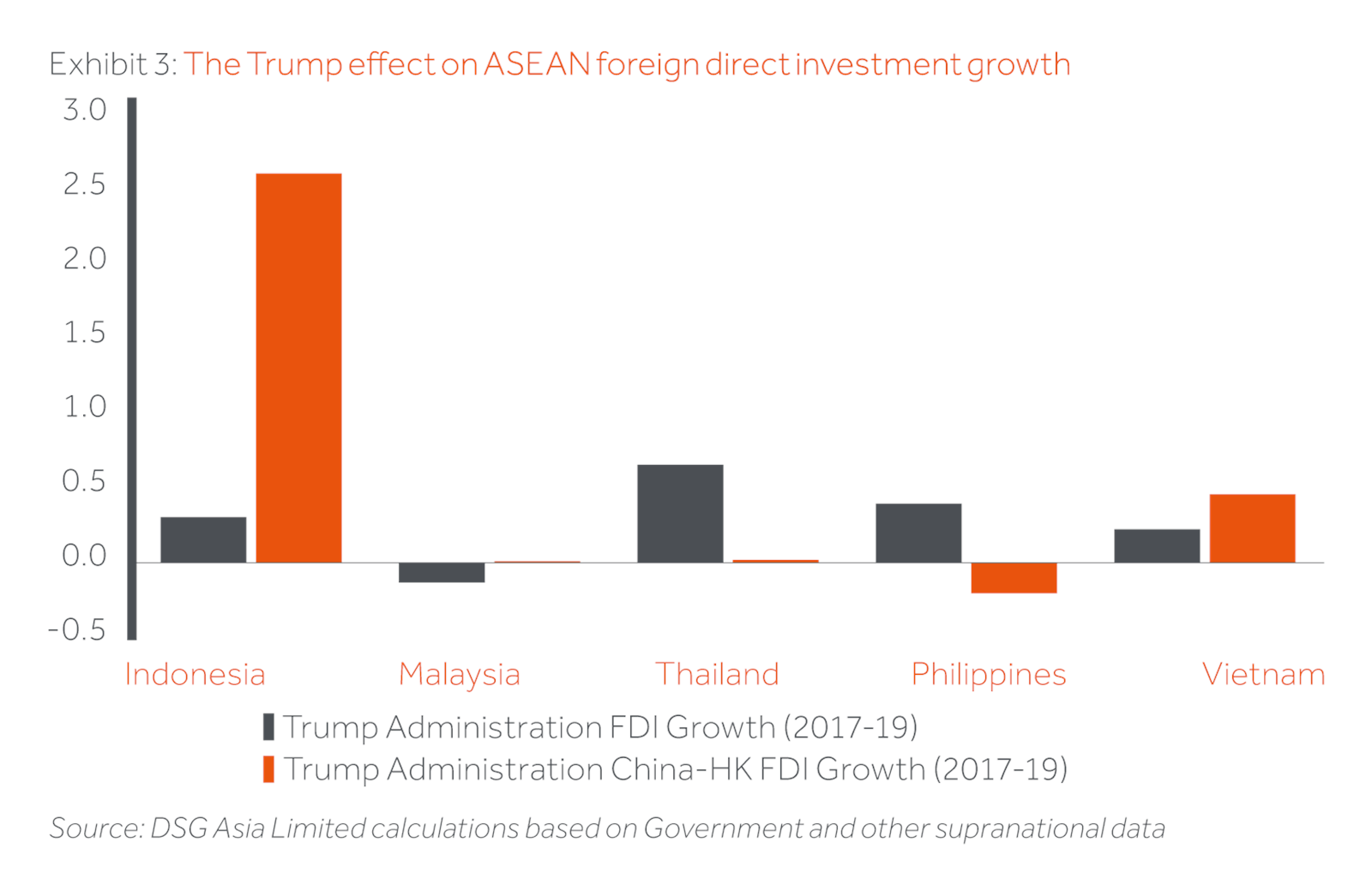

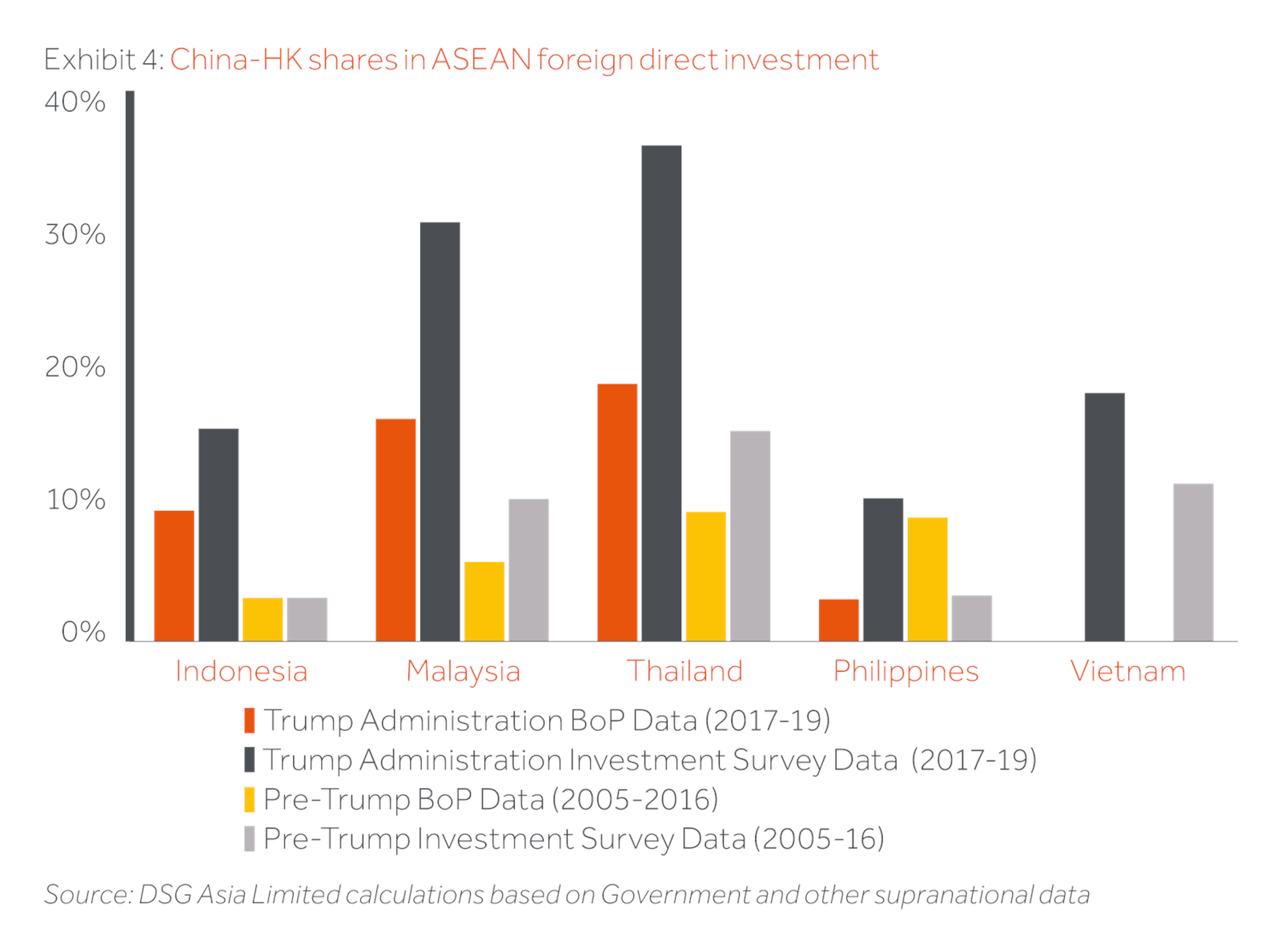

For Exhibit 3 and Exhibit 4, I have crunched the numbers on ASEAN foreign investment realisations from both the individual country investment survey and balance of payments (BoP) data series. I have then compared the foreign investment outcomes under the Trump administration (2017-2019) with those prevailing over the decade immediately preceding his election.

Turning first to pure growth rates under Trump, all the countries surveyed with (to me) the surprising exception of Malaysia, have seen significant pick-ups in inflows. However, with the exception of Indonesia, the China contribution has been rather muted (and seems to have been overwhelmingly concentrated in the resource sector) while despite the Duterte-Xi love-in, Beijing seems to have, if anything, scaled back its rate of deployments into the Philippines. It would seem to be non-Chinese firms who have been increasing their investments both here and in Thailand.

Nonetheless, there is no doubt that, from a very low base only a decade ago, China has become an increasingly important supplier of FDI. Hence if the POTUS and his posse really want to stem the flow of Chinese products into the US, they are going to have to develop an even more sophisticated (sic) pan-regional tariff and monitoring regime. Or indeed put in place measures to boost American savings rates…

Unlike ASEAN, North Asia has always been rather more closed to foreign investment. Hence any resurgence in export-oriented capex is largely reliant on re-onshoring by local producers with significant operations in China.

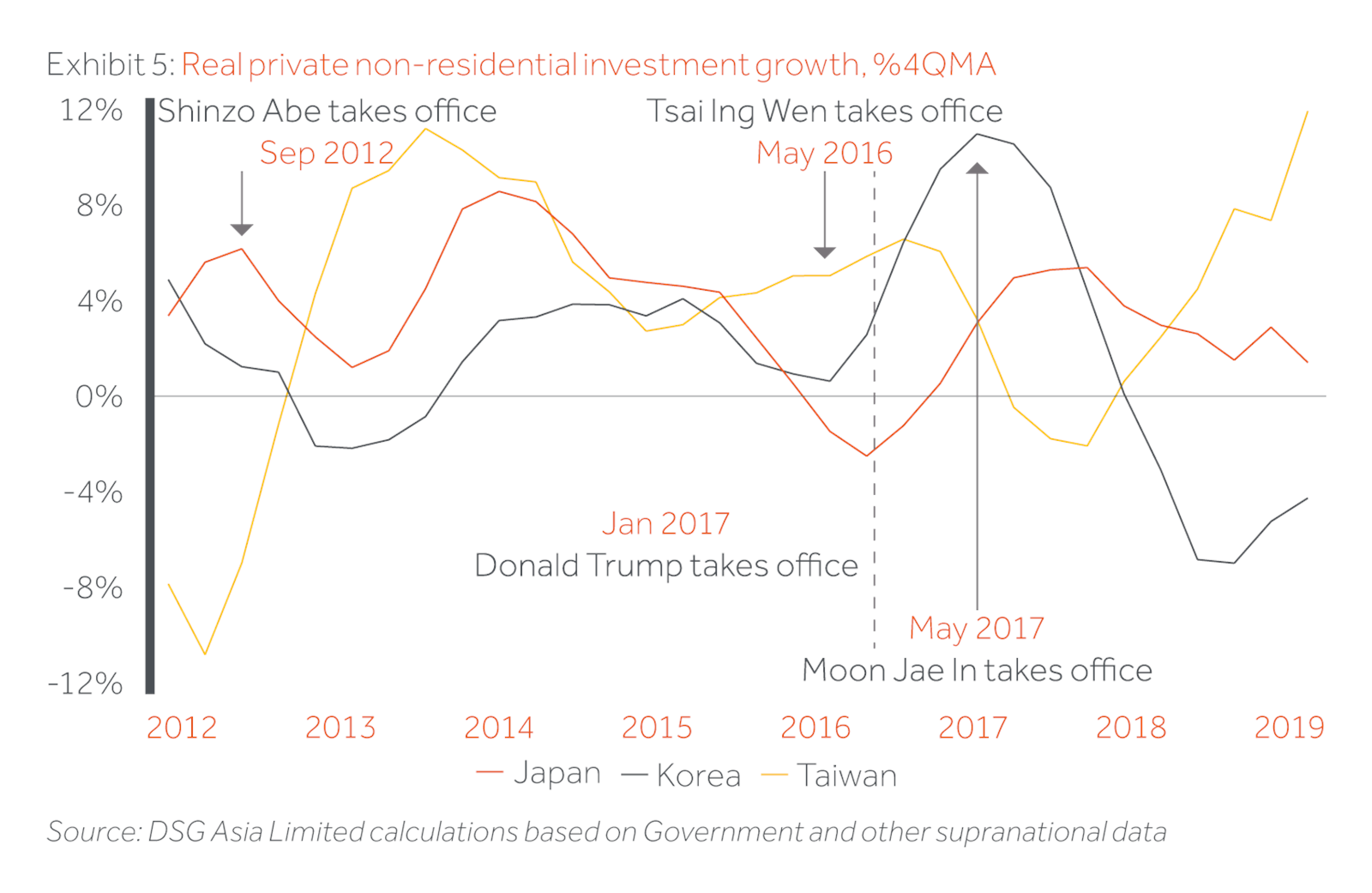

This, in turn, is a function of a) company flexibility, b) the friendliness (or otherwise) of the investment environment, and c) labour supply and regulations. Increasing divergence has been seen across the region with capex surging in Taiwan, chugging along steadily in Japan, but contracting heavily in Korea.

Taiwan’s outperformance owes little to Government policy – no DPP administration over the decades has demonstrated much in the way of economic competence – yet is rather due to its companies being more tightly integrated into the Mainland while also, traditionally, being more operationally flexible.

As indeed are Taiwan’s SMEs. While an unemployment rate below 4% suggests little or no labour market slack, the potential to attract back some of the more than 400,000, often skilled Taiwanese working in China potentially provides a flexible, skilled reservoir that dwarfs that possessed by Japan or Korea.

The caveat is that these days, such workers are often paid significantly more on the Mainland than they are back home. Domestic wages will likely need to adjust upwards, therefore, but given real wage growth has averaged only 0.5% per annum over the past decade, this may be no bad thing.

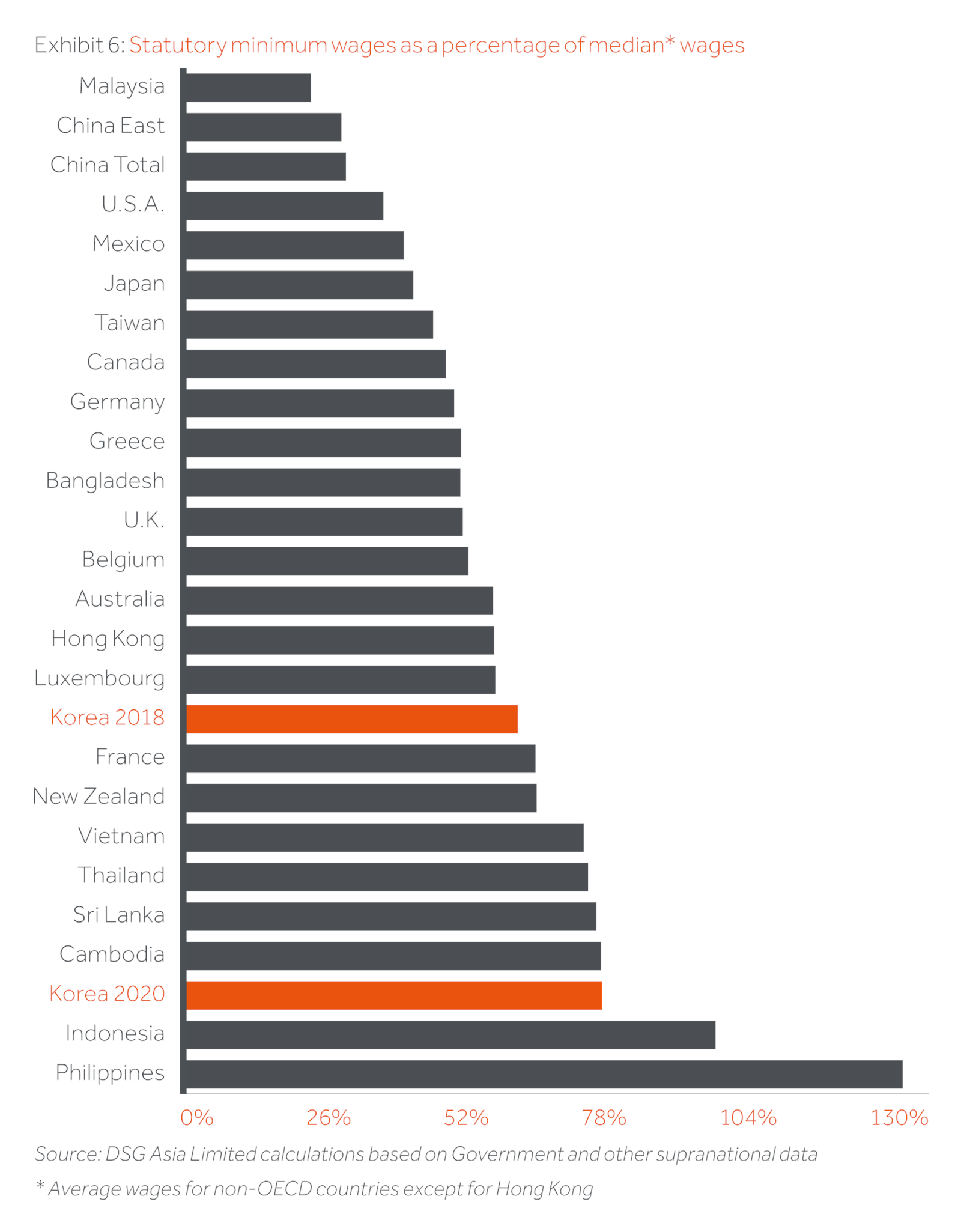

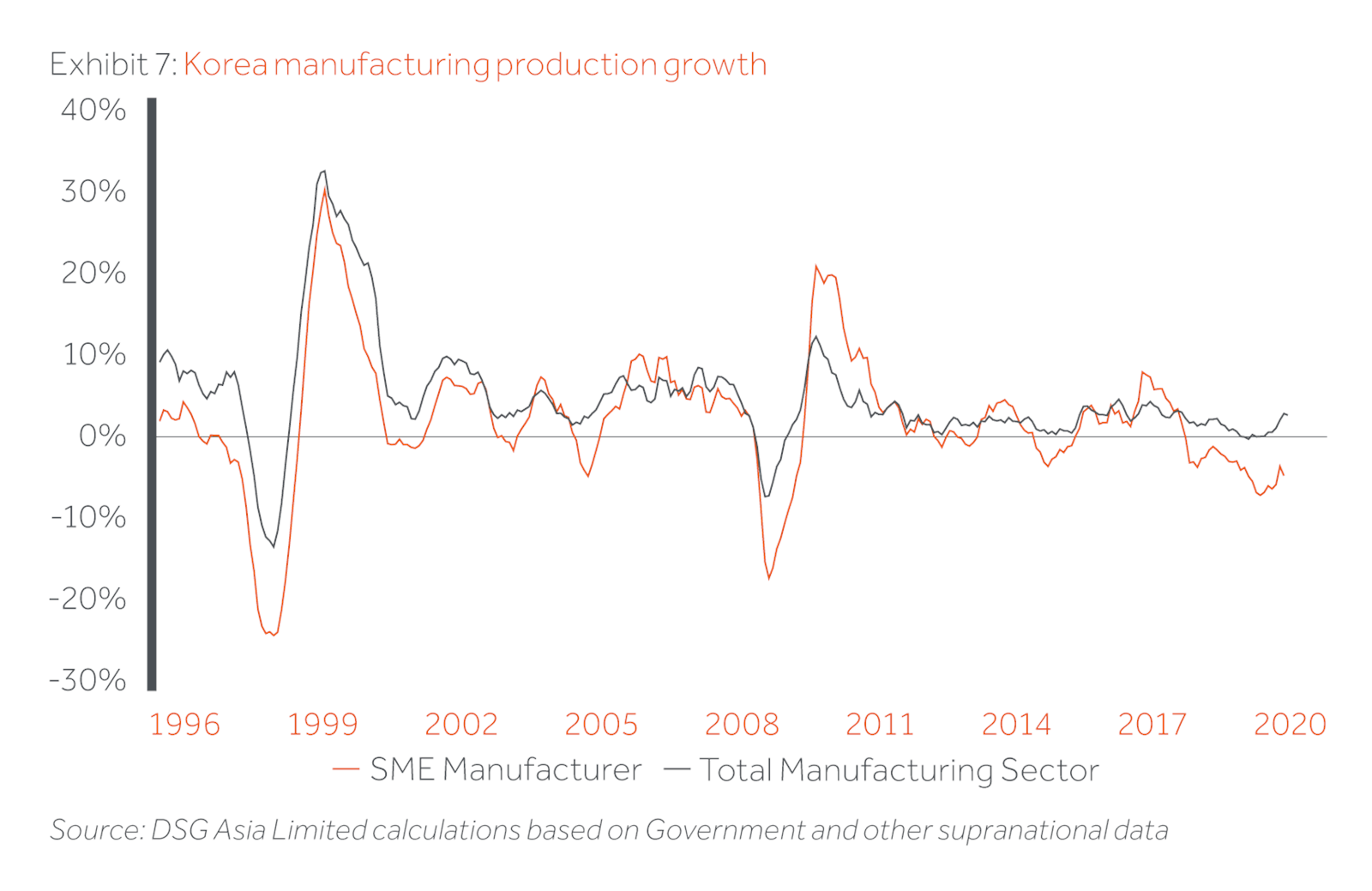

By contrast, Government policy in Korea, especially with respect to the labour markets, has been outright destructive under Moon Jae-in. In mandating a succession of double-digit minimum wage increases, the left-leaning President’s intentions have doubtless been noble in the context of rising inequality and a less-than-generous welfare system.

Yet driving minimum wages to the highest levels in the OECD relative to the median (Exhibit 6), in the context of a global manufacturing recession and an already struggling SME sector (Exhibit 7), has not been exactly helpful. Meanwhile, choosing this moment to pick a trade fight with Japan has provided the (rancid) icing on the cake.

Somewhere in the middle of Taiwan and Korea stands Japan. Given the 1 October 2019 increase in GST from 8% to 10% and the Rugby World Cup, the data are, understandably, going to be messy in the coming couple of quarters. Japan does not feel like is an economy on the brink of a major collapse though as transpired following previous GST rises.

Arguably, it was Japan’s lousy timing rather than the GST changes themselves that caused major dislocations in 1997 and 2014, and the COVID-19 outbreak, if prolonged, could yet still provide an unhappy reprise.

Failing this, the domestic economy appears to be in better shape today while this time the Government was far more careful in designing a range of fiscal offsets to smooth the transition to the higher tax rate.

For sure, in the context of weak global trade, Japan is hardly booming while despite decades of ever-more expansionary monetary policies, inflation has remained stubbornly low.

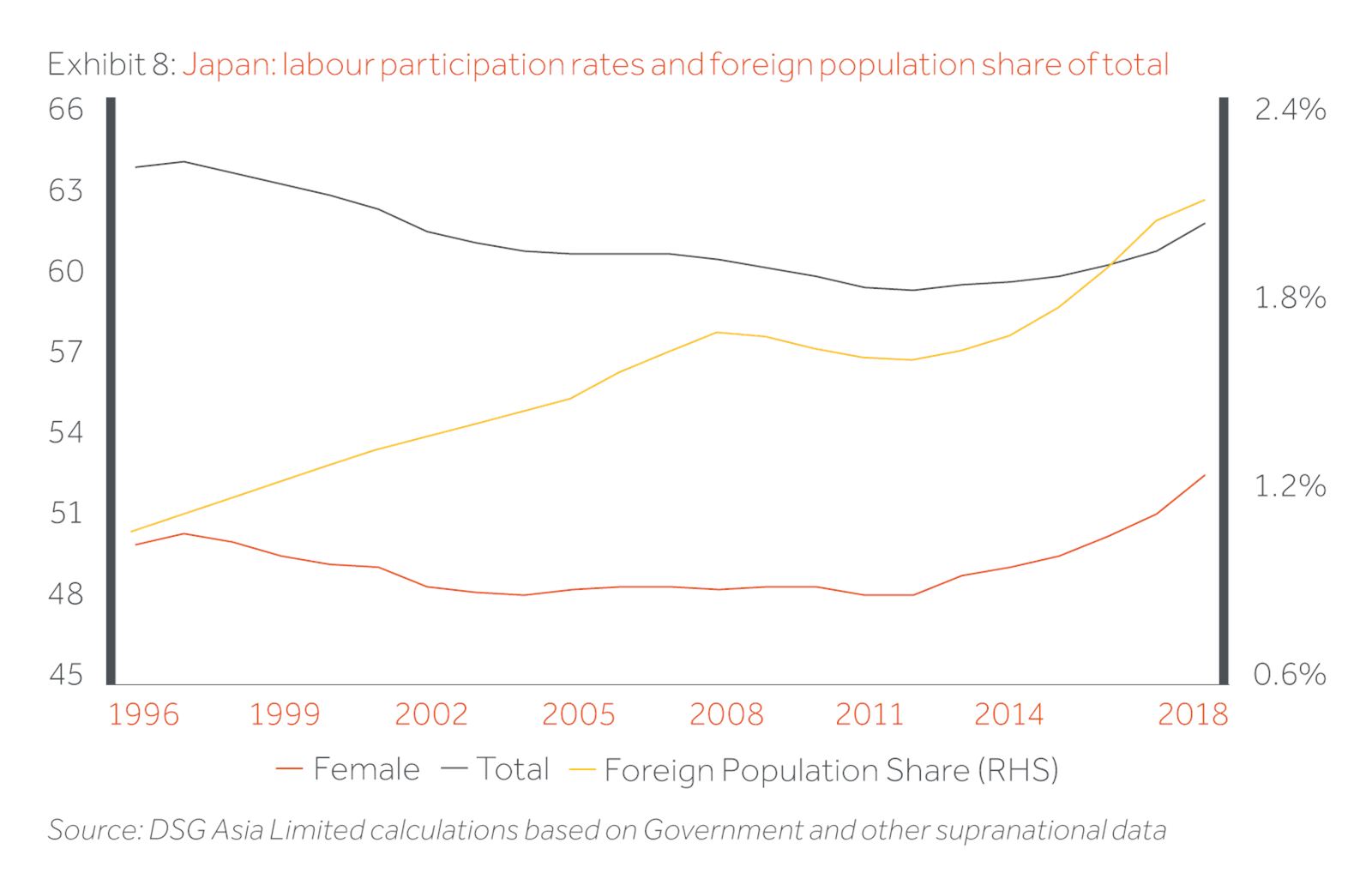

Nevertheless, with the labour supply continuing to expand steadily driven by increasing numbers of female and foreign workers seeking work, household income growth remains more than respectable.