Margaret Keenan – a 91-year-old grandmother – is an unlikely history maker. On 8 December 2020 she was the first person in the world outside of trials to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

A few months later, the number of vaccine shots administered globally had mushroomed to over one billion in 152 countries according to Bloomberg. Vaccination rates will shortly exceed 20 million per day.

This sounds impressive. But under 10% of the world population has been vaccinated. The wealthiest 27 countries with 11% of world population have administered over 40% of all vaccines. Sir Jeremy Farrar, Director of Wellcome Trust, a pre-eminent epidemiologist who leads one of the largest health charities in the world, speaks eloquently of the need “to vaccinate the entire world”.

The wealthiest 27 countries with 11% of world population have administered over 40% of all vaccines

It takes time to vaccinate the entire world, even before accounting for vaccine diplomacy and inequality. Manufacturing interruptions and vaccination infrastructure challenges will retard progress. Societies will adopt to acceptance of vaccination at differing rates.

Vaccines will at times fail to meet public expectations of safety and efficacy (however high and unrealistic these expectations may be). Vaccine diplomacy will also play a considerable role in outcomes.

The downsides are obvious. To date much of the debate has been around the Astra Zeneca (‘AZ’) vaccine and potential side effects. Most recently, health officials in China have questioned efficacy rates for their own vaccines. The one dose vaccine developed by Johnson and Johnson has also attracted attention on safety grounds.

Many of these concerns are genuinely felt and well documented. Yet equally, the diplomatic prize of being a dominant vaccine supplier may fuel disinformation campaigns as we have already seen with cyber based attempts to discredit specific vaccines.

More to the point is relative cost. The deal struck between the University of Oxford and AZ was for supply to end-customers at cost until the WHO declared the pandemic stage of COVID-19 over. Such cost has been widely reported as around $4 a dose. By contrast, press reports suggest that Chinese vaccines are selling for $9-10 a dose and that Pfizer and Moderna vaccines can cost up to $30 a shot.

Taken at face value, therefore the recent decision by the African Union to eschew AZ must involve extra costs for purchase, running into many billions of dollars. It remains to be seen how far the UN based Gavi alliance and its Covax program can fill this gap. Either way fiscal stress is liable to increase rather than decrease in our markets if less expensive vaccines are jettisoned.

The harrowing tragedy of India’s second wave has also impacted global vaccination rates. Onshore manufacturers in India are focussing on supplying the domestic market. As such they are unable to meet previously contracted requirements. Sadly this shortfall is felt in poorer countries not least because of the supply shortages being felt by the Covax program.

All of this matters hugely for the countries concerned and more broadly for global economic recovery. Face-to-face services, including tourism, will not fully recover until travellers and host countries acknowledge reciprocal levels of ‘safety’, read vaccination levels.

Likewise, it would be surprising to see a sustained upturn in global fixed capital formation given material supply overhang in many industries. All of which leaves households and Governments to take up the slack. The household sector in developed countries has had a huge wealth transfer through fiscal action and a rise in enforced savings and can be counted on to drive demand in the next 12-24 months, albeit constrained by rolling lockdowns. Governments are however tapped out.

Whilst it will be a rare country that does not post higher 2021 growth given base effects, recovery to anything approaching 2019 activity levels seems a remote hope for at least 1-2 years minimum for all but the USA and China. IMF estimates do not see pre 2019 trend growth rates being regained until at least 2024 or beyond for most emerging countries.

It’s mainly fiscal

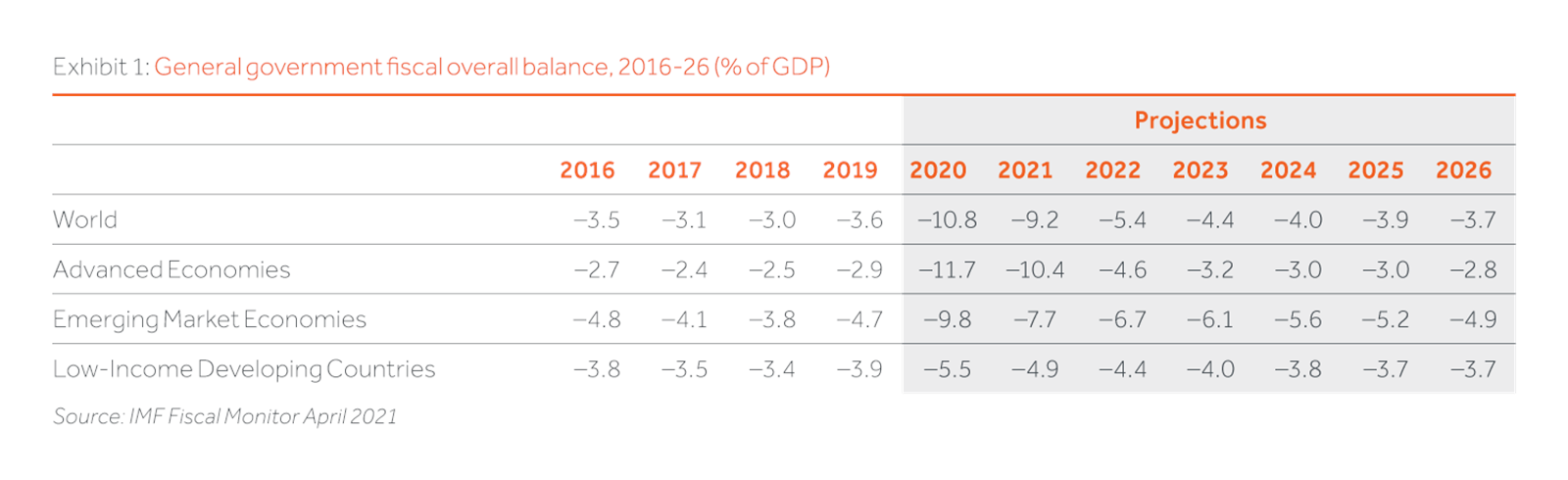

COVID-19 has been an income and expenditure shock – and in combination significantly larger than one would normally expect in a ‘normal’ business cycle. The resulting deficits were enormous in 2020 and whilst lower in the next 2-3 years, will still see debt stock rising.

As a result, indebted economies are increasingly vulnerable to rises in rates, changes in commodity prices, rising corporate bankruptcies and revenue collection risk. As Exhibit 1 suggests, advanced economies are more indebted than Emerging Markets, but this partly reflects the relative depth of domestic financing systems.

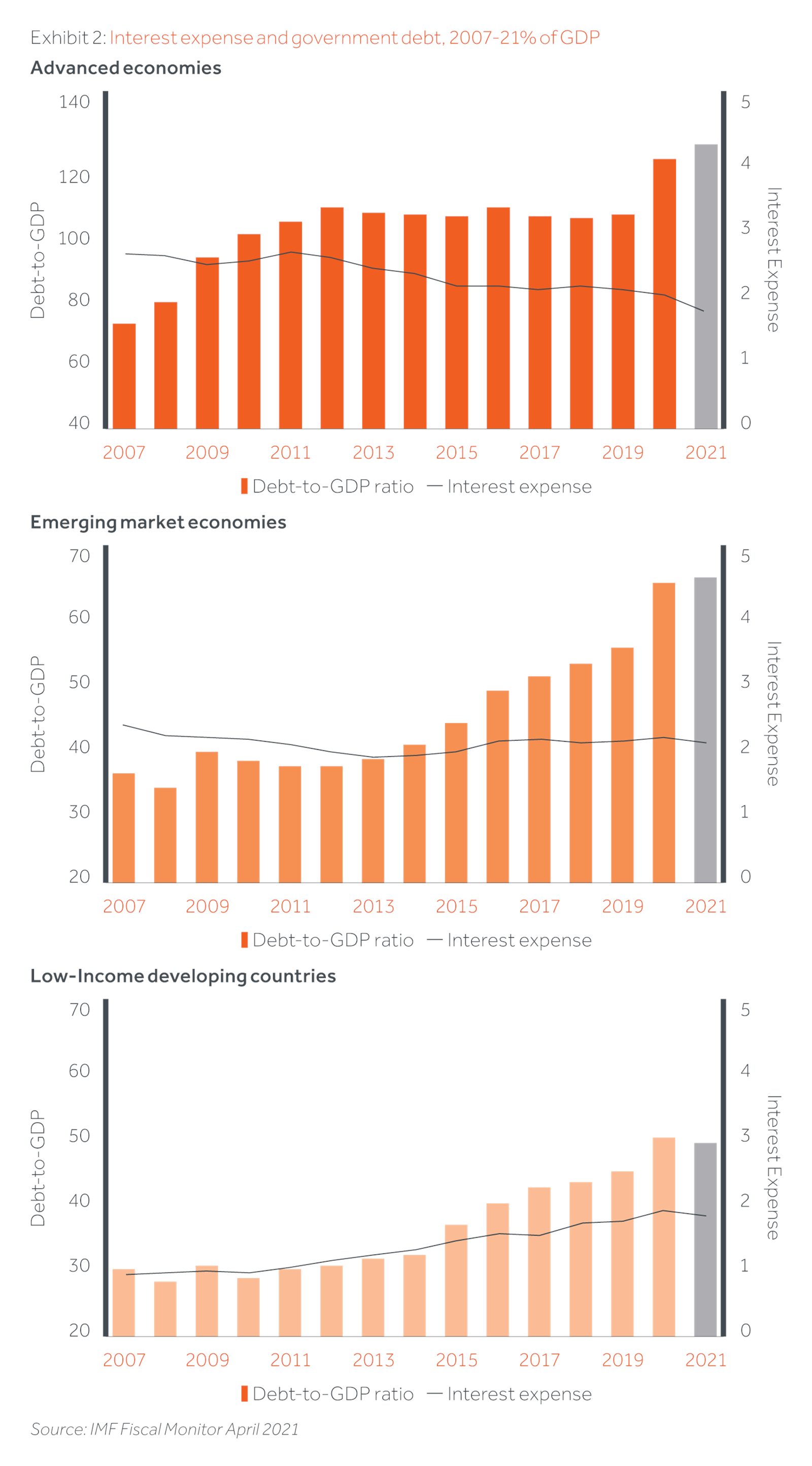

The legacy of a long period of declining rates means it will take some time for these issues to crystallise, but it is worth looking at Exhibit 2 and remembering that if revenues are 10-15% of GDP and debt service costs rise from 2 to 3% of GDP, this means that 20% of revenues are being used in debt service.

Debt management strategies under such circumstances often involve shortening duration resulting in increasing rollover risk. As an example, Brazil has seen the average duration of Government debt drop from 3.6 years to 2 years since 2018, largely due to debt management strategies in 2020.

The heavy reliance on domestic funding has driven the BRL onshore bills to bonds spread up by 500 basis points in recent months, materially increasing the cost of funds for the private sector.

One bright spot for a number of developing economies of course is the rise in commodity prices seen this year. In turn, this reduces but does not eliminate fiscal deficits given that the yield on minerals royalties net of collection cost is far superior to other indirect taxes.

So, oil based economies in the Middle East have had some respite with an oil price nearer $70 a barrel than $30. Similar dynamics exist in Nigeria and Colombia, whilst rallying industrial metals prices are alleviating the worst impacts in Peru, Chile, Brazil and South Africa, at least for now.

Counting currencies

A year ago, many currencies were in free fall. Material declines in current account deficits backed up by the actions of the Federal Reserve in opening dollar swap lines have reduced much of this risk.

But significant risk pockets still exist, and our research suggests that policy instability – for instance in Turkey and Brazil – can still lead to material currency declines. An increase in global risk appetite, allied to domestic reforms which incentivise private sector risk taking, would help.

In short, we see fiscal dynamics as the current ‘Achilles’ heel’ for Emerging Markets countries. East Asia and India have limited exposure to these risks, reflecting long duration funding and strong domestic buffers.

These risks increase as one travels West and South with epicentres in Brazil and to a lesser extent Nigeria. Currency risks still exist (not least because of the rallies from oversold positions a year ago) but these can be linked to country specific issues rather than across the board.